Scientists have discovered a link between low household income and faster decay of the white matter inside our brains. While levels of this white matter decline with age, living in poverty seems to speed up the process.

The findings are based on an analysis of 751 individuals aged between 50 and 91, carried out by a team of researchers from the University of Lausanne and the University of Geneva in Switzerland.

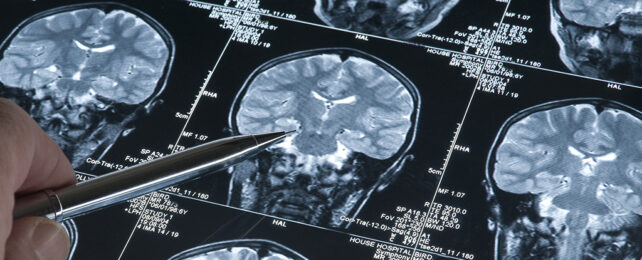

After accounting for factors such as age, sex, and some key health issues, the study found that those in poorer households showed more signs of white matter aging in their brains in MRI scans, and scored lower on cognitive tests than those in wealthier households.

"This study aimed to provide insight into the pathways linking socioeconomic exposures – household income, last-known occupational position, and life course socioeconomic trajectories – with brain microstructure and cognitive performance in middle to late adulthood," write the researchers in their published paper.

White matter is pretty essential when it comes to moving messages and signals around the brain, and the amount of it that's available has an effect on cognitive ability. Living in poverty – or as the researchers put it, being exposed to "chronic socioeconomic disadvantage" – has long been associated with poor health and faster cognitive decline.

Here, the team wanted to take a closer look at why that might be, finding that the number of fibers branching out from each neuron (neurite density) and the extent of protective coating on these fibers (myelination) seemed to be contributing to a more rapid breakdown in white matter.

Previous studies exploring brain and socioeconomic levels mostly considered overall brain volume. Now that the finer structural associations have been identified, the possible mechanisms behind them can be further investigated.

This work detected how freely molecules – mostly water – move through the brain (mean diffusivity), which appears to be dependent on the amount of myelin and the density of neuron branches, indicating they are important factors to focus on.

However, in people from higher household incomes, these markers of white matter brain aging didn't have as much of a negative effect on cognitive performance.

"Individuals from higher income households showed preserved cognitive performance even with greater mean diffusivity, lower myelination, or lower neurite density," write the researchers.

It appears that having more money acts as a sort of buffer against cognitive decline – despite the physical changes observed, suggesting there is another mechanism at play beyond the changes seen so far.

Research hasn't looked closely at the relationship between brain microstructure and income levels before, and now that this association has been identified, it can be further investigated – in large, more diverse groups, and across larger economic disparities.

In this case the team didn't examine all of the various social and environmental factors that might be affecting white matter – like depression, for example. Overall though, their work provides further evidence that being better off financially means a healthier life too.

"These findings provide a detailed neurobiological understanding of socioeconomic differences in brain anatomy and associated cognitive performance," write the researchers.

The research has been published in JNeurosci.