It's no secret that corvids are capable of some amazing feats of creative and intelligent thinking, but a newly discovered ability has us stunned.

A team of scientists has shown that crows can 'count' out loud – producing a specific and deliberate number of caws in response to visual and auditory cues. While other animals such as honeybees have shown an ability to understand numbers, this specific manifestation of numeric literacy has not yet been observed in any other non-human species.

"Producing a specific number of vocalizations with purpose requires a sophisticated combination of numerical abilities and vocal control," writes the team of researchers led by neuroscientist Diana Liao of the University of Tübingen in Germany.

"Whether this capacity exists in animals other than humans is yet unknown. We show that crows can flexibly produce variable numbers of one to four vocalizations in response to arbitrary cues associated with numerical values."

The ability to count aloud is distinct from understanding numbers. It requires not only that understanding, but purposeful vocal control with the aim of communication. Humans are known to use speech to count numbers and communicate quantities, an ability taught young.

When toddlers are learning to count, learning the specific numbers associated with specific quantities can take a bit of time to master. In the interim, children can sometimes use random numbers to make a vocal tally. Instead of counting "one, two, three," they might say "one, one, four," or "three, ten, one." The number of vocalizations is correct, but the words themselves are jumbled.

The biological origin of symbolic counting is unknown, but since crows are known to understand difficult numerical concepts such as zero, Liao and colleagues thought they represented a good candidate for investigating more sophisticated number skills.

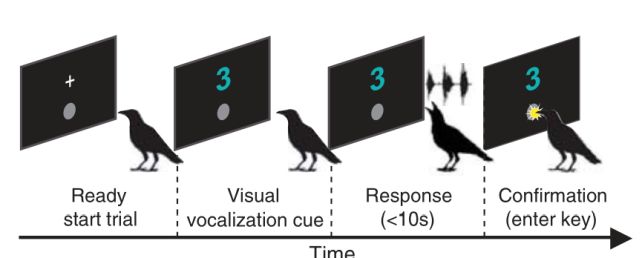

They conducted their study on three carrion crows (Corvus corone), which the researchers trained to produce a variable number of vocalizations, between one and four, upon being shown an arbitrary symbol or audio cue. Once they had produced the requisite number of caws, the crows then had to peck a target to signify that they were done.

All three crows, the researchers found, were able to produce the correct number of caws in response to the cues, with the occasional error mostly presenting as one caw too many or too few.

This, the researchers say, is similar to the way human toddlers count, using a non-symbolic approximate number system that is planned in advance before the first vocalization.

Interestingly, the timing and sound of the first vocalization in a sequence were linked to how many vocalizations were made subsequently, and each vocalization in a sequence had acoustic features specific to its place in that sequence.

The feat is especially impressive for crows since deliberate vocalizations are more difficult to produce and have longer reaction times than, say, pecks or head movements.

It could indicate a previously unknown channel for avian communication in the wild. Chickadees, for instance, produce a greater number of "dee" sounds in their alarm calls for larger predators.

"Our results demonstrate that crows can flexibly and deliberately produce an instructed number of vocalizations by using the 'approximate number system', a non-symbolic number estimation system shared by humans and animals," the researchers write in their paper.

"This competency in crows also mirrors toddlers' enumeration skills before they learn to understand cardinal number words and may therefore constitute an evolutionary precursor of true counting where numbers are part of a combinatorial symbol system."

The research has been published in Science.