Once upon a time, our world was home to many giants.

Actually, it wasn't so long ago. Once the dinosaurs had had their day, our planet was home to a whole new range of giant animals, from sloths that towered over humans, to wooly mammoths, to huge wombats and kangaroos, to the magnificent giga-goose.

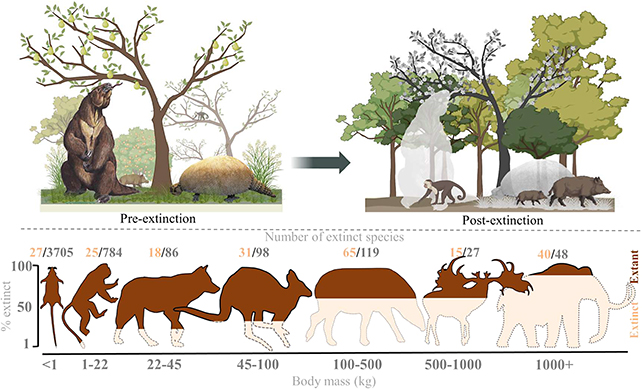

Between around 50,000 and 10,000 years ago, nearly 200 of the world's largest animal species disappeared forever, leaving nothing but their humongous bones (and burrows). It's unclear what ultimately claimed these magnificent creatures.

During the time frame in which the megafauna disappeared, the world warmed and an ice age ended, suggesting one potential mechanism: climate change. Meanwhile, our own species was expanding into new lands, chasing the wealth of resources that came with the retreating ice. And so the debate over the roles of these two potential contributing factors has raged.

Now a new study on the decline of giant herbivorous mammals – megaherbivores – points a finger at humanity.

Fossils show that, 50,000 years ago, there were at least 57 species of megaherbivore. Today, just 11 remain. They include notable behemoths such as hippos and giraffes, as well as several species of rhino and elephant, many of which continue to dwindle.

Such a dramatic decline, researchers say, is inconsistent with climate change as the sole cause.

"The large and very selective loss of megafauna over the last 50,000 years is unique over the past 66 million years. Previous periods of climate change did not lead to large, selective extinctions, which argues against a major role for climate in the megafauna extinctions," says macroecologist Jens-Christian Svenning of Aarhus University in Denmark

"Another significant pattern that argues against a role for climate is that the recent megafauna extinctions hit just as hard in climatically stable areas as in unstable areas."

The new study consists of a comprehensive review of the available evidence since the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. These include locations and timings of extinctions, habitat and food preferences, estimated population sizes, evidence of human hunting, human population movements, and climate and vegetation data going back millions of years.

We know that humans coexisted with megafauna, and we have evidence of some species being hunted to extinction. We know our ancestors were capable of hunting large animals effectively.

"Early modern humans were effective hunters of even the largest animal species and clearly had the ability to reduce the populations of large animals," Svenning says.

"These large animals were and are particularly vulnerable to overexploitation because they have long gestation periods, produce very few offspring at a time, and take many years to reach sexual maturity."

The new research shows that these human hunters were effective enough to significantly contribute to many extinctions. The megaherbivores, the team found, died out across a variety of climate scenarios, in which they had been able to effectively thrive even during times of change. Most of them would have adapted well to a warming environment, the researchers found.

And they died at different times and at different rates – but all of those times were after humans had arrived, or developed the means to hunt them. In fact, the exploitation of mammoths, mastodons, and giant sloths was pretty consistent everywhere humans went.

Perhaps the reason the mammoths hung on at Wrangel Island after the mainland population disappeared was because there were no humans there.

It's a sobering thought, especially since the megafauna that survive today are declining thanks to human exploitation, as found in a 2019 study. Some 98 percent of endangered megafauna species are at the risk of dying out because people won't stop eating them.

"Our results highlight the need for active conservation and restoration efforts," Svenning says. "By reintroducing large mammals, we can help restore ecological balances and support biodiversity, which evolved in ecosystems rich in megafauna."

Small wonder the rest of the animal kingdom fears us.

The research has been published in Cambridge Prisms: Extinction.