An exoplanet identified in 2017 as one of the most promising locations for life to flourish outside the Solar System has just become even more promising – and a whole lot weirder.

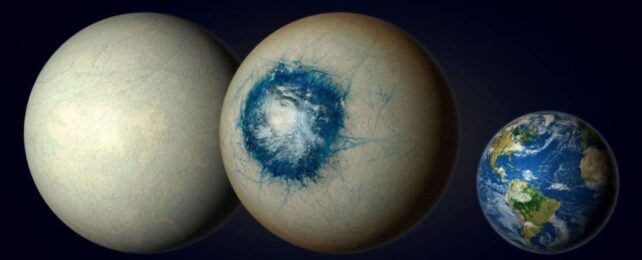

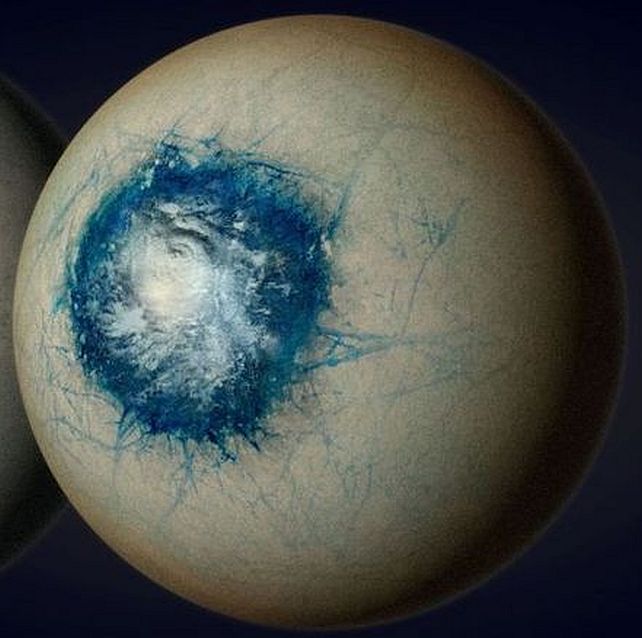

The alien world LHS-1140b shows signs of being an 'eyeball' planet, with a global ocean capped in ice, and a single, iris-like region some 4,000 kilometers (around 2,500 miles) across permanently gazing at its host star.

"Of all currently known temperate exoplanets, LHS-1140b could well be our best bet to one day indirectly confirm liquid water on the surface of an alien world beyond our Solar System," says astrophysicist Charles Cadieux of the University of Montreal. "This would be a major milestone in the search for potentially habitable exoplanets."

LHS-1140b, the discovery of which was announced just a few years ago, has a radius around 1.73 times that of Earth's and 5.6 times its mass; bigger than our own planet but still small enough to be considered a terrestrial world. It's also orbiting a lot more closely with its star than Earth does, completing an entire orbit in just shy of 25 days.

If that star was at all like the Sun, that would be way too close for life. Instead it is a cool, dim, red dwarf – so the distance between star and exoplanet is smack-bang in what we call the habitable zone. That's not so cold that all surface water would freeze, but not so close that it would steam away into oblivion.

Even so, the close proximity means that the exoplanet is likely to be tidally locked. That's when its rotational period falls into lockstep with its orbital period, so that the same side is always facing the star. It's the same phenomenon that we see with Earth and the Moon, and why we never see its far side from Earth.

Being in a habitable zone doesn't automatically mean it's got the necessary conditions to support life. To learn know more about LHS-1140b's chemistry, we need to peer into its atmosphere, if it has one. And this is what Cadieux and his colleagues have done, using the power of JWST.

At just under 50 light-years away, the system is close enough to us that we can collect detailed information about the way light changes when the exoplanet passes between Earth and the star. Some of the starlight will pass through the atmosphere; as it does so, some wavelengths are absorbed or amplified by atoms within. Precisely which atoms are at work can be determined by looking at which wavelengths are being affected.

By doing this, the researchers were able to tentatively ascertain the presence of nitrogen, the dominant ingredient in Earth's atmosphere. If LHS-1140b were more gaseous, like a tiny little Neptune, it would have a more hydrogen-rich atmosphere. The presence of nitrogen suggests a secondary atmosphere – one that formed after the exoplanet's birth, rather than with it.

In a study published last year, the team also combined LHS-1140b's density and radius to calculate its density. They got a figure of 5.9 grams per cubic centimeter. That is not dense enough for a world that's purely made of rock; given its size, the best fit is either a mini-Neptune or an ocean-covered water world. If we rule out the mini-Neptune, what we have left is a global ocean exoplanet.

Factoring in tidal locking, though, this global ocean might not look the way you might think. The side that is permanently facing away from the star could be cold enough to freeze over. Only the patch directly facing the star would be warm enough to thaw, resulting in a world that looks like a creepy eyeball hovering in space.

That patch, however, could reach a very balmy 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit) on the surface – warm enough for a thriving marine ecosystem.

We don't know for sure what's going on, but it looks like the most promising candidate we have to date for an exotic alien ecosystem outside of our own planetary neighborhood, so you can bet your bottom dollar that there's going to be a lot more staring right back at that weirdo (possible) eyeball.

"Detecting an Earth-like atmosphere on a temperate planet is pushing Webb's capabilities to its limits – it's feasible; we just need lots of observing time," says physicist René Doyon of the University of Montreal.

"The current hint of a nitrogen-rich atmosphere begs for confirmation with more data. We need at least one more year of observations to confirm that LHS 1140b has an atmosphere, and likely two or three more to detect carbon dioxide."

The research has been accepted into The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and is available on arXiv.