Researchers have discovered patterns in the brain that reflect the effectiveness of deep brain stimulation therapy for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), potentially leading to improvements in the way that the condition is handled individually for each case.

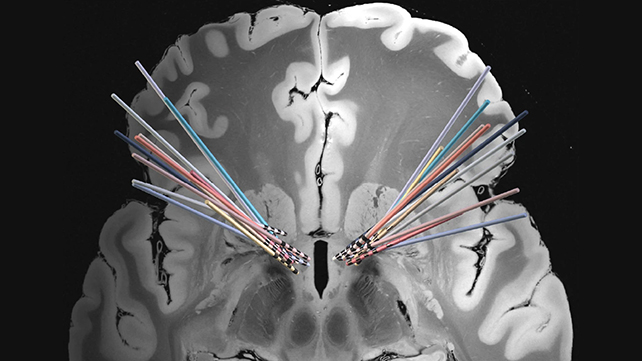

A team led by researchers from the Baylor College of Medicine in Texas used brain scans from 12 people with treatment-resistant OCD, who were undergoing deep brain stimulation (DBS) – a treatment that monitors and controls the activity of precise patches of neural tissue via implanted electrodes.

"Recent advances in surgical neuromodulation have enabled long-term continuous monitoring of brain activity in OCD patients during their everyday lives," says biomedical engineer Nicole Provenza, from Baylor College of Medicine.

"We used this novel opportunity to identify key neural signatures that can act as predictors of clinical state."

Often used in cases where conventional treatments haven't worked, DBS is an increasingly common method of treating neural disorders, including OCD. Around two-thirds of OCD patients show improvements after DBS treatments, but monitoring the treatment's progress and determining the precise level of stimulation isn't always straightforward.

Tracking low-frequency brain oscillations in the theta (4-8Hz) to alpha (8-12Hz) range, the researchers found a specific, regular 24-hour circadian rhythm in ventral striatum neural activity at the 9Hz (theta-alpha border) frequency that was disrupted by the application of DBS treatment.

The team thinks this disruption might be a sign of change in the patient's rituals and neurological responses to events that happen through the day.

"This expanded repertoire may be a reflection of the more diverse brain activity pattern," says psychiatrist Wayne Goodman, from the Baylor College of Medicine. "Thus, we think this loss of a highly predictable neural activity indicates that the participants engaged in fewer repetitive and compulsive OCD behaviors."

Mapping neural patterns and how they change in response to DBS could reveal which patients are responding well to the treatment, which doses are working best, and which patients might have to move on to another treatment.

It's thought that around 2.3 percent of the adult US population will experience OCD at some point in their lives, so if improvements in treatment can be found, then we're talking about changes in millions of lives.

"We are excited by the potential possibility that such similar neural activity signatures may underlie other neuropsychiatric disorders and could serve as biomarkers to diagnose, predict, and monitor those conditions," says Provenza.

The research has been published in Nature Medicine.