Kindergarten-age kids excel at lots of things, but focusing efficiently on a task is not typically one of their strong suits.

Research suggests many children at this age find it hard to concentrate on details most relevant to an assignment, often spending time and energy collecting information that won't help them.

According to a new study of 4-, 5-, and 6-year-olds, this is not because kids generally can't understand the task or pay attention. Their brains are mature enough to do both, the authors report.

Instead, kids in this age range seem to broadly distribute their attention for one of two possible reasons; sheer curiosity, or it may indicate their working memory is not developed enough to avoid 'over-exploring' while they pursue a goal.

"Children can't seem to stop themselves from gathering more information than they need to complete a task, even when they know exactly what they need," says Vladimir Sloutsky, co-author of the study and professor of psychology at Ohio State University.

In previous research, Sloutsky and his colleagues demonstrated this broad distribution of attention, finding children seem incapable of ignoring irrelevant information to help them complete tasks more efficiently, as adults tend to do.

Yet the reasons why children distribute their attention so broadly remained elusive.

Even when kids do successfully focus on a task (in this case, motivated by small rewards like stickers), they still over-explore, consuming information that won't help them achieve their goal, the researchers show in the new study.

Hoping to shed light on why this tendency is so strong, the researchers designed an on-screen experiment to test whether distractibility could offer an explanation.

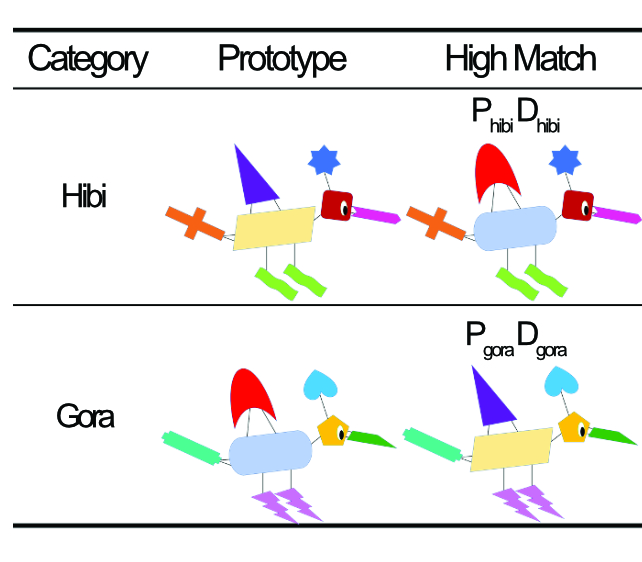

Children and adults were instructed to identify two types of fictitious, bird-like creatures on a computer, which the researchers called a Hibi and a Gora. Each creature had a unique combination of colors and shapes for various body parts, including horn, head, beak, central body, wing, feet, and tail.

For six body parts, the color-shape combo predicted a creature's identity with 67 percent accuracy. One body part, however, was always a 100 percent match to only one creature type, something both kids and adults learned quickly in the early going.

Starting with the parts hidden from view, the researchers required both children and adults to select each part individually to reveal which type of creature they were dealing with. Study participants received higher scores for identifying the creature quickly, revealing as few body parts as possible.

Adults aced this, the study found. Once they knew which body part would always reveal the creature's identity, they always uncovered that body part first, thus unmasking the creature with the fewest possible steps.

Kids approached the situation differently, though. Like adults, they would also start by uncovering the body part that always predicted a creature's identity, demonstrating they too had learned that association and understood its strategic value.

But instead of sealing in their answer, the kids would continue uncovering more body parts before identifying the creature.

"There was nothing to distract the children – everything was covered up. They could do like the adults and only click on the body part that identified the creature, but they did not," Sloutsky says. "They just kept uncovering more body parts before they made their choice."

Of course, it's possible the kids just enjoyed the individual revelation of each body part more than they cared about their success in efficiently identifying the creature. Maybe they just liked tapping the buttons, the researchers point out.

To account for that, another experiment offered both kids and adults an 'express' button, which would reveal the entire creature and all of its body parts with a single tap. They also retained the option to tap and reveal each body part individually.

Children mostly chose the express button in this setup, the study found, suggesting they hadn't been merely tapping buttons for fun earlier.

More research will be needed to clarify the origins of this extra exploration, the researchers say. While it may be driven by curiosity, Sloutsky suspects it's because children of this age do not yet have a fully developed working memory.

"The children learned that one body part will tell them what the creature is, but they may be concerned that they don't remember correctly. Their working memory is still under development," Sloutsky says.

"They want to resolve this uncertainty by continuing to sample, by looking at other body parts to see if they line up with what they think," he says.

As children's working memory develops, so too should their confidence in what it can do, resulting in more adult-like behavior, Sloutsky adds.

The study was published in Psychological Science.