Every single second, a million cells in your body die. So where does all that waste go?

A new study reveals a surprisingly cannibalistic cleanup method. Some dead stem cells in the mammal body appear to become food for their neighbors, researchers in the US have found.

These living stem cells are drawn to the 'whiff' of a freshly made corpse by two sensitive receptors, which are spatially tuned to the 'smell' of death and life.

"[The mechanism] only functions when each receptor picks up the signal it is attuned to," explains cellular biologist Katherine Stewart from The Rockefeller University in the US.

"If one of them disappears, the mechanism stops operating. It's a really beautiful way to keep the area clean without consuming healthy cells."

The study was conducted on the hair follicles of mice in the latter stages of their lives.

Previous studies have found that when cell death becomes widespread in the mouse hair bulb, it is cells in the lower outer sheath that clear the corpses.

But until now, it wasn't clear what happened when death reached the follicles' stem cells.

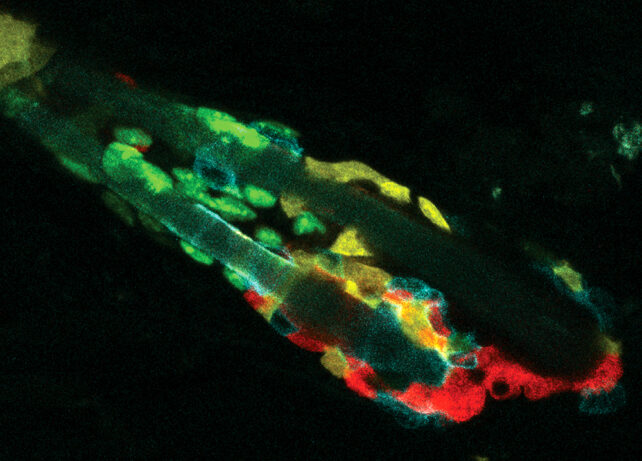

In experiments, Stewart and her colleagues have shown that when hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) die, they are quickly gobbled up by their neighbors before the immune cells, like macrophages, for instance, can come in and do the same.

"I was very surprised to find that the hair follicle stem cells were actually the first responders, especially because mouse skin is fairly well-endowed with macrophages, so they're not even that far away," says Stewart.

By holding off inflammation, it seems that HFSCs are protecting each other against an overactive immune system.

When HFSCs are unable to eat each other, their corpses disrupt the long-term maintenance of the stem cell pool.

In cases where they can eat each other, on the other hand, some HFSCs consume as many as six of their dying neighbors.

Eating the dead could be a way to recycle fuel for energy, explains cellular biologist Elaine Fuchs, who runs the lab at Rockefeller, "but as soon as the debris is cleared, they must quickly return to their jobs of maintaining the stem cell pool and making the body's hair."

The whole process appears to be carefully controlled via two receptors on HFSCs that function like 'on' and 'off' switches. One receptor responds to a "find me" lipid signal, secreted by a dying neighbor. The other responds to a growth-promoting retinoic acid, secreted by other healthy cells.

"A dying cell triggers the mechanism to begin, and when there are no dead cells left, the lipid signal disappears, leaving only the retinoic acid signal from the healthy cells," says Stewart.

"This tells the program to dampen back down. It's so elegant in its simplicity."

The researchers speculate that this rapid detection of corpse cells may function in other tissues in the mammal body, too, although further research will now be needed to test that idea.

Regardless, the team argues their discovery represents a "powerful mechanism for rapidly clearing dying cells and preventing tissue damage."

The study was published in Nature.