Scientists have taken a major step towards finding elusive types of tiny, 'ghost-like' particles, and potentially new physics.

For the first time, neutrinos have been spotted by the Short-Baseline Near Detector (SBND) at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab).

It's a significant moment in the decades-long quest to add to what we know about some of the most abundant particles in the Universe.

With such tiny masses and only the slimmest of chances of interacting with other particles, 100 trillion of them pass through our bodies each second without us being any the wiser. Yet their properties are so unique, their very existence could help explain why we have a Universe of atoms, molecules, stars, and galaxies.

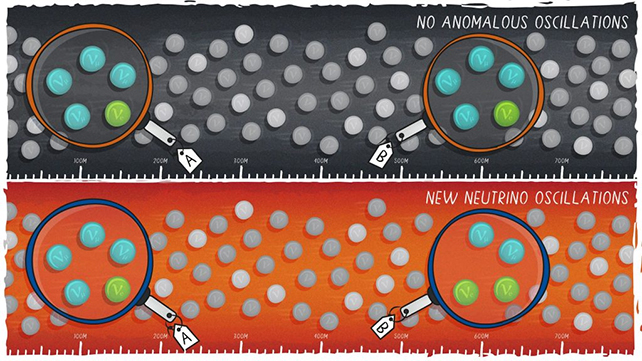

We already know about three kinds of neutrinos – muon, electron, and tau – but some experiments suggest there's another one waiting to be found, a so-called 'sterile' form that is even more ghost-like than the rest. Confirming its existence is one of the key jobs of the newly operational SBND.

"We think neutrinos could help us get at some huge questions, like finding a more complete theory of nature at the smallest scales, or even why our matter-filled Universe exists at all," says experimental particle physicist Andrew Mastbaum, from the Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences in New Jersey.

Work on the SBND has been going on for almost a decade, so the appearance of the first neutrino reactions has been a long time coming. It's filled with 112 tons of super chilled liquid argon that can detect the fleeting brush of a neutrino's interaction via the weak nuclear force.

Other detectors around the globe, such as Antarctica's IceCube Neutrino Observatory, attempt to snare the countless neutrinos showering down from cosmic reactions. Experiments here on Earth also churn out neutrinos in processes we have much better control over, making it invaluable that we detect those particles as well.

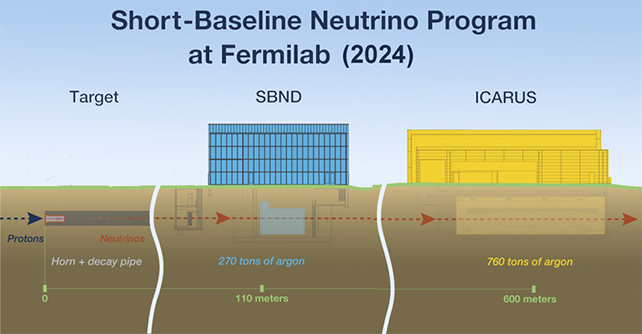

The SBND is going to join up with the ICARUS (Imaging Cosmic And Rare Underground Signals) machine, installed in 2017 and around 500 meters (or a third of a mile) away. Together, they'll analyze the particle accelerator beams generated from Fermilab.

As many as around 7,000 neutrino interactions could be detected per day – a huge number considering how rare these interactions usually are. The two detectors can then watch for traces from the collisions, and just maybe, spot something that looks like a new variation on the neutrino.

"Detecting the photons produced by the beam helps us determine the start time and duration of the particle interactions," says physicist Richard Van de Water, from Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

"That information complements the tracking of particles produced in these interactions, giving us a fuller picture of the particle physics occurring."

With SBND able to study neutrinos with greater precision than ever before, it's hoped that it might spot other patterns and anomalies that fall outside the Standard Model of physics, including potentially dark matter. Don't be surprised to hear more from Fermilab, the SBND and ICARUS in the coming years, as operations scale up.

"Understanding the anomalies seen by previous experiments has been a major goal in the field for the last 25 years," says physicist David Schmitz, from the University of Chicago.

"Together SBND and ICARUS will have outstanding ability to test the existence of these new neutrinos."