In Jamestown, Virginia – the first permanent English settlement in America – there's a distinctive black tombstone thought to mark the resting place of a knight. Now, researchers think they've figured out where the stone came from.

While the stone marker is described as "marble" in historical documents, at the time this term was often applied to any kind of rock that could be polished. Dating from 1627, the slab of mineral is actually limestone.

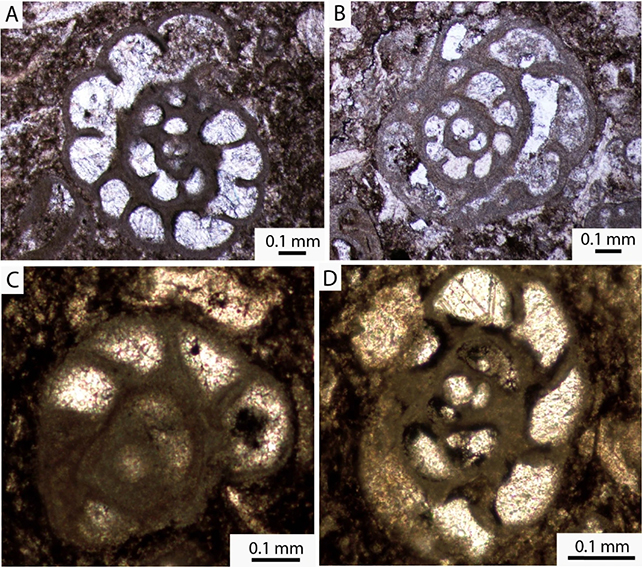

The research team, from Dickinson College in Pennsylvania and the California Geological Survey, looked at the tiny shells of single-celled organisms embedded in the sedimentary rock to help place its source, using the microfossils to determine it originated from Belgium.

"Wealthy colonists in the Tidewater region of the Chesapeake Bay at this time preferentially selected black 'marble' for their gravestones that was actually polished, fine-grained, black limestone," the researchers write in their published paper.

"The iconic knight's tombstone at Jamestown is one such stone. The goal of this project was to determine the source of this stone to help understand trade routes at this time."

It's unlikely Jamestown's English settlers would have had either the tools or skills to make tombstones of this nature, suggesting the highly-polished ornament would have been imported.

An analysis of tombstone fragments revealed fossilized remnants of a diverse group of shelled protist called foraminiferans, including the species Omphalotis minima, Paraarchaediscus angulatus, and Paraarchaediscus concavus, and one more each from the Endothyra, Omphalotis, and Globoendothyra genuses that weren't identified to the species level.

The combination of co-occurring microfossils excluded North America as an origin of the limestone slab, pointing instead to a place over the Atlantic, most like somewhere like Ireland of Belgium.

With similar colonial tombstones around the Chesapeake Bay having previously been sourced from Belgium, and the fact the European country had been been well established as a hub for exporting black 'marble' ever since Roman Times, the researchers were confident an artisan in this region had crafted the grave marker.

As far back as the Middle Ages, the members of the wealthy upper class in England had been commemorating their dead using these pricey tombstones, something the Jamestown settlers would have known about.

"Little did we realize that colonists were ordering black marble tombstones from Belgium like we order items from Amazon, just a lot slower," first author and geoscientist Markus Key from Dickinson College told Sandee Oster at Phys.org.

Because of its age and prominent position in the local church, experts have long thought the grave belonged to the knight Sir George Yeardley, who arrived in Jamestown in 1610. He quite possibly ordered the tombstone as a mark of his status and wealth.

Though the study wasn't focused on the tombstone's owner, the fact the stone was shipped from Belgium further confirms the hypothesis the grave belonged to Yeardley, who would've been looking to follow the fashions of his homeland.

"It is hoped that the results of this study help refine the geography and timing of the seventeenth-century North Atlantic trade routes between Continental Europe (especially Belgium), England, and colonial Virginia," write the researchers.

The research has been published in the International Journal of Historical Archaeology.