Fatigue is one of the most frequent and debilitating symptoms of long COVID, and yet it is also one of the hardest to measure objectively.

A new study suggests the extreme mental and physical fatigue experienced by many long COVID patients is, in fact, observable in the central nervous system.

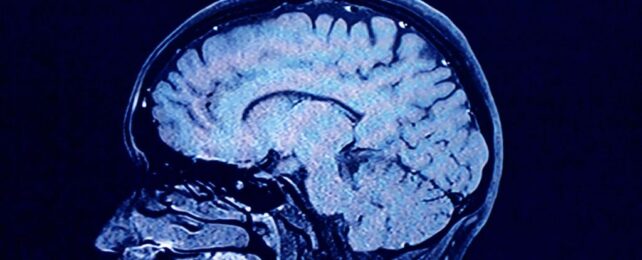

Scanning the brains of 127 long COVID patients, scientists found some parts of the brain were communicating with others in a slightly altered way.

These regions include the frontal lobe, the temporal lobe, and the cerebellum, and while it's not clear how long the changes might last, the pattern could be used to identify those battling ongoing fatigue.

"These findings suggest a role of central nervous system involvement in the pathophysiology of fatigue in post-COVID syndrome," write researchers at the Complutense University of Madrid in Spain.

"The existence of several brain characteristics associated with fatigue severity detected by magnetic resonance imaging could constitute a neuroimaging biomarker to objectively evaluate this symptom in clinical trials."

The frontal lobe is the part of the brain associated with higher executive functions, like planning, reasoning, and problem solving. Meanwhile, the temporal lobe is associated with memory and processing, and the cerebellum is linked to movement, posture, and balance.

All three areas have previously shown changes in connectivity among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME).

CFS/ME comes with many of the same symptoms as long COVID; however, it remains unclear how the two illnesses relate.

Recent findings suggest brain changes associated with long COVID mirror those of CFS/ME, but further research using larger and more diverse sample sizes is needed.

The new study on long COVID, led by neuropsychologist Maria Diez-Cirarda, does not consider CFS/ME, but it analyzes the brain scans of 127 people who had contracted SARS-CoV-2 at least three months before. Around 74 percent of participants were female, and most had only been sick with COVID-19 once.

Roughly 87 percent reported symptoms of global fatigue, including physical or mental fatigue, and 86 percent said they were suffering from cognitive complaints, like memory, attention, or processing issues.

Ultimately, those with global fatigue, physical fatigue, or cognitive complaints showed reduced connectivity between the frontal and occipital brain regions. They also showed increased connectivity between the cerebellar and temporal areas.

Mental fatigue, however, stood out. It was associated with distinct changes in the left prefrontal areas, the anterior cingulate, and the left insula – the central hubs of a known mental fatigue network.

Changes to white matter were also found in the brains of long COVID patients with lingering fatigue. White matter contains the nerve fibers that connect neurons, and these are covered in white sheaths, which protect and allow messages to be sent faster.

In long COVID patients, the recent study suggests that physical and mental fatigue is "partly related to several microstructural changes, including demyelination."

Demyelination is when the insulating sheath that protects neurons and transmits electrical signals is damaged, resulting in reduced functionality, such as muscle weakness, blurry vision, or slurred speech.

Interestingly, the current brain study found no changes in gray matter, which contains the bodies of neurons. Previous studies have shown reduced gray matter in COVID patients, but this shrinkage was recorded during or shortly after an infection, and it may not last over the longer term.

Given how malleable the brain can be, it's important that future studies investigate the changes of long COVID over greater lengths of time. Further research could also investigate how fatigue due to long COVID compares to other conditions, like ME/CFS or multiple sclerosis.

"The involvement of the central nervous system in the pathophysiology of fatigue in post-COVID syndrome paves the way for the use of non-invasive brain stimulation techniques to alleviate fatigue in these patients," the researchers conclude.

The study was published in Psychiatry Research.