Life on Earth is pretty complicated these days, but it wasn't always so. The fossil record hints at simpler times, millions of years ago, when each organism consisted of just one cell.

But around 575 million years ago – for reasons we can only guess at – more complex life forms with multiple cells began to appear in the fossil record. We call them the Ediacaran biota.

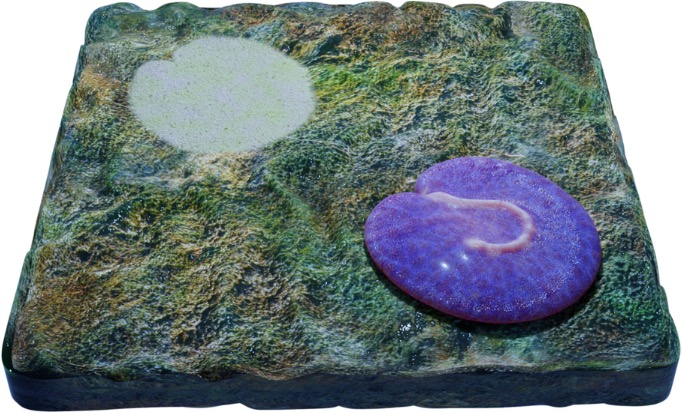

The traces of one of these early complex creatures has just been unearthed in the South Australian outback, and its intricate design rivals all other fossils before it. Behold, one of Earth's earliest animals:

Ok, so it's a flattened, circular blob with a mysterious question mark shape for a butt crack.

A collaboration between US scientists and paleontologists from the South Australian Museum brings us this remarkable prehistoric lump, Quaestio simpsonorum.

They know it's an animal because of the features it shares with living members of the kingdom: multiple cells, the ability to move, and a body plan organized into different halves.

And they found not one, but more than a dozen of these things, along with trace fossils – the imprints of their blobby bodies preserved forever in the now-petrified mat of microscopic algae and bacteria that Quaestio once lurked in.

Some of these impressions show slightly offset outlines distinct from the harder edges of the animal's imprint, evidence that these were among the first animals capable of moving on their own.

"One of the most exciting moments… was when we flipped over a rock, brushed it off, and spotted what was obviously a trace fossil behind a Quaestio specimen – a clear sign that the organism was motile; it could move," Harvard University evolutionary biologist Ian Hughes says.

A little smaller than the size of a human palm, the Quaestio's distinctive question-mark shape – for which it was named – distinguishes a left and right side, a sign of bilateral symmetry, along with a crucial asymmetrical twist.

"There aren't other fossils from this time that have shown this type of organization so definitively," Florida State University geologist Scott Evans says.

Asymmetry is a component of modern-day animals, including humans, and Quaestio might just be the first to evolve this mathematically complicated quirk.

"Studying the history of life through fossils tells us how animals evolve and what processes cause their extinction, be it climate change or low oxygen," says paleontologist Mary Droser, lead scientist for Nilpena Ediacara National Park, where the fossil was discovered.

As the site of Earth's oldest fossil animals, the Ediacara biota, the national park is being considered for UNESCO World Heritage Site listing, to protect the valuable records of our Earth's living history it contains.

"We're the only planet that we know of with life, so as we look to find life on other planets, we can go back in time on Earth to see how life evolved on this planet," Droser says.

This research was published in Evolution & Development.