Forced to sacrifice all but two items from a list, more than half of 16- to 22-year-olds surveyed in a 2011 poll would sooner give up their sense of smell than technology such as their phone or laptop.

Compared with other senses, human olfaction can seem like a muted afterthought. Yet researchers have uncovered a surprising effect this taken-for-granted sense has on the way we take in every breath of air.

A team from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel measured the nasal airflow in 31 individuals with an intact sense of smell and 21 volunteers with 'anosmia', finding a shocking surplus of sniffs in the scenters.

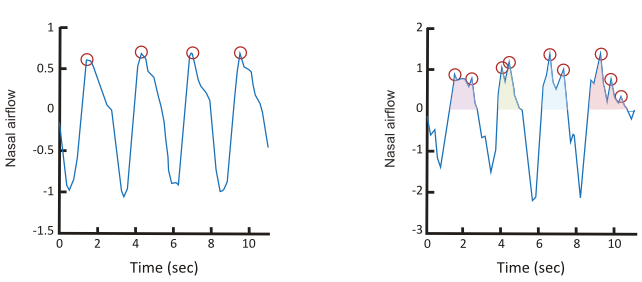

Monitored over a 24-hour period, the group that could detect scents added a small but significant drag of air with every breath, amounting to an incredible 240 more inhalation peaks per hour.

Not only is the newfound physiological behavior more than 80 percent accurate in objectively diagnosing anosmia, or loss of smell, it could help explain why in older adults, an inability to detect odors more than triples the odds of death compared with people with their olfactory system in full working order.

As so many experienced following infection from COVID, the loss of smell is no trivial symptom. When it's taken from us, something seems woefully amiss.

Warm, familiar fragrances vanish while food takes on bland characteristics, sucking the joy out of eating. At worst, it robs individuals of a valuable way to tell when a morsel has turned rancid, potentially putting them at risk of food poisoning.

Considering our ability to smell could also save our skins by alerting us to signs of fire or gas, it's not hard to see how a quick sniff test could reduce our risk of an early grave.

According to the researchers, it's possible other, less obvious physiological changes may also contribute to the increased risk of death among those who have lost their sense of smell.

It's well established that the relative amount of air we inhale through our noses increases as the intensity or pleasantness of an odor decreases. Presented with a strong scent, we're less likely to gulp up a lungful through our nostrils, even while we sleep.

Given odors change how we breathe, the researchers wondered if a loss of smell may also be detectable as a general respiratory behavior.

Strapping on wearable devices that sensitively measure airflow through the nose, the study's volunteers went about a normal day eating, talking, and sleeping while every breath was counted and assessed.

While the total number of breaths and volume of inhaled air remained comparable between the two groups, those who could detect smells displayed a curious double, or even triple 'spike' every time their lungs expanded.

Just what this stuttered inhalation achieves – if anything at all – isn't clear. Equally, it's hard to say what damage its absence may be causing among anosmics, who according to some estimates could represent more than 15 percent of the population.

Yet our brain's functions are strongly entwined with our respiration, affecting not just how we think and feel, but also how we memorize and control our moods.

"Such shifted respiratory patterns, and particularly nasal airflow patterns, may have an impact on physiological and mental health," the researchers suggest in their report.

Future studies that provide a higher resolution on sampling the airflow, evaluate actual abilities to detect odors, or even incorporate a more diverse sample of smellers and non-smellers could provide further insights into this surprising contrast in breathing pattern, and perhaps determine its impact on our health.

For now, it might be worth keeping a spare phone in your back pocket, just in case. Your sense of smell could be far more important to your well-being than you think.

This research was published in Nature Communications.