For the first time, we've got a three-dimensional picture of a magnetic skyrmion. This tiny, spiraling flaw in the magnetic properties of some materials could find uses in next-gen electronics storage devices and quantum computers.

While two-dimensional predictions of skyrmions have proved valuable, new research from the US and Switzerland shows the particle-like swirls aren't confined to flat surfaces. They're more complex, making determining their 3D structure important.

The new study, led by physicist David Raftrey from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, gives us a better understanding of the fundamentals of magnetic materials. Considering how widely they are used, there are many potential applications.

"The presence of skyrmions or other magnetic textures at the microscopic level fundamentally determines the properties, behavior, and functionality of magnetic materials," the team writes in their published paper.

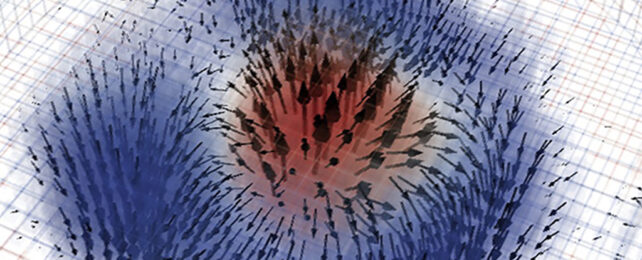

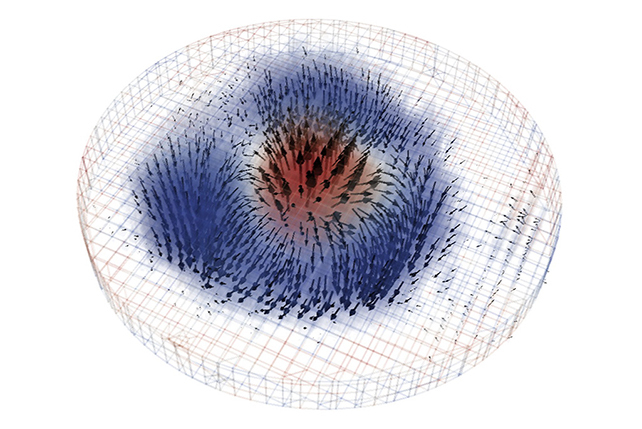

At the nanoscale, in certain magnetic materials, skyrmions can be found as stable, standing waves consisting of swirls of contrasting electron spins. These swirls can be triggered to move in particular ways, through the application of an electric charge or a magnetic field.

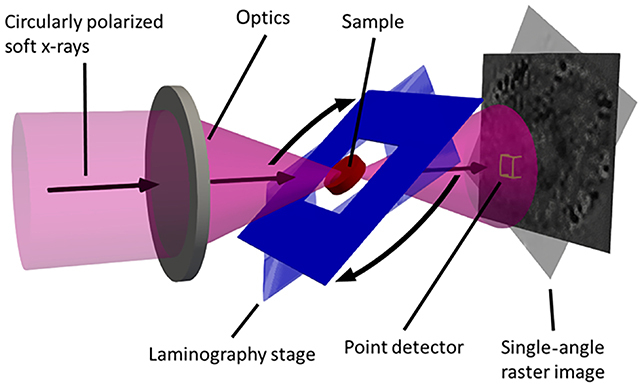

Raftrey and his colleagues used an advanced technique called magnetic X-ray laminography – a process akin to medical CT scans for simpler materials. As an object is moved and rotated, new readings are taken, building up a 3D picture.

In this case, the object was a very small magnetic disk containing skyrmions, just 800 nanometers across and 95 nanometers thick. Stack around a thousand of them on top of each other, and you're up to the thickness of a standard piece of paper.

This wasn't a quick process – taking months overall – but the researchers eventually came up with the improved understanding of skyrmion spin structures they were looking for, thanks to the use of some sophisticated algorithms to combine the X-ray images.

"You can basically reconfigure and reconstruct [the skyrmion] from these many, many images and data," explains Raftrey.

Now that these structures have been mapped in 3D for the first time, we know how they are shaped, how they interact, and how they vary layer-by-layer – a big improvement on the 2D images we had previously.

What physicists like about skyrmions is that they're very stable, very speedy, and very difficult to break up. That suggests they might be useful for storing the 1s and 0s of basic data in a more compact and efficient way than traditional approaches do.

It's a field of science known as spintronics, using electron spins instead of electrons as the foundation of computing systems. As previous studies have shown, it would mean major jumps forward in computer size and miniaturization.

"Relying on the charge of the electron, as it is done today, comes with inevitable energy losses. Using spins, the losses will be significantly lower," says materials scientist Peter Fischer from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

"Our results provide a foundation for nanoscale metrology for spintronics devices."

The research has been published in Science Advances.