We know that the tiny tardigrade is one of the toughest creatures on the planet, and a newly discovered species of these miniature 'water bears' has given experts a deeper insight into how they can withstand harmful radiation.

When researchers from multiple institutions across China looked closely at the genome of the new species – Hypsibius henanensis – discovered six years ago, they discovered 14,701 protein-coding genes, of which 4,436 (30.2 percent) were unique to tardigrades.

They also exposed the small creatures to blasts of radiation, watching to see how gene expression and protein production would be affected – and the sort of biological superpowers these genes might provide for the tardigrades.

"Studies on several tardigrade species have documented that they are the most radiation-tolerant animals on Earth," write the researchers in their published paper.

"They exhibit resistance to gamma radiation of up to 3,000 to 5,000 grays (Gy), around 1,000 times higher than the lethal dose for humans."

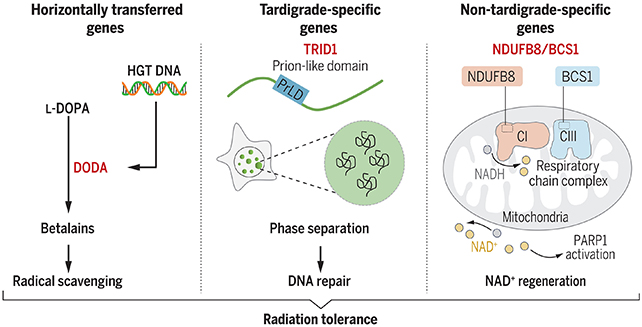

The team made three key observations: a gene called DODA1, potentially transferred from bacteria, produces pigments known as betalains, and these help to neutralize the harmful molecules that are generated by radiation.

Second, DNA was being repaired much more quickly than normal, thanks to a tardigrade-specific protein called TRID1, and third, production increased of two other proteins, BCS1 and NDUFB8 (which also help with energy supply).

While some of these tricks were already known about, like high-speed DNA repair, the close analysis of H. henanensis gives us more detail about what exactly is going on – and how the humble tardigrade stays so robust.

Combined together, these three processes that emerge in response to radiation help to protect the tardigrades against its dangerous effects. The next step is to see how generally these protective measures are deployed across all tardigrade species.

"Whether the radiation tolerance of other tardigrade species occurs through conserved mechanisms or is specific in the genus Hypsibius warrants additional study," write the researchers.

There are around 1,500 species of tardigrade that we know about, and the new study matches previous research into Hypsibius exemplaris tardigrades: when radiation is detected, the creatures ramp up the activity of repair genes.

And these findings go way beyond the tardigrade. As small as it is, the ways this animal can cling to life are helpful in figuring out how to better protect our own bodies in extreme environments (not least during long-term space flights, for example).

It's thought that tardigrades first appeared before the Cambrian, which is around 541 million years ago. To survive that long, you need to have plenty of tricks at your disposal for staying alive.

"The capability of tardigrades to survive under the harshest conditions continues to reshape our concept of the limits of animal life on Earth," write the researchers.

The research has been published in Science.