The dead, if you are to heed the warning of burials conducted hundreds of years ago, may not always lay so quietly in their grave.

Over a span of more than 1,000 years, in different parts of Europe, burials were conducted seemingly to keep the dead safely in their graves, and not walking about causing havoc among the living.

The formal name for practices of this kind is apotropaic burial rites. Informally, they have a more bone-chilling name: the vampire burial.

Poland, where apotropaic rites were common in the medieval and post-medieval periods, has folklore rich with the vjesci and the upiór. It's in locations such as this that burials have been found with heavy stones placed on the body, blades lodged across the neck, body parts removed, or even stakes driven through the torso.

What isn't known is precisely what it was the living feared, whether vampirism or some other form of revenant, or a supernatural threat to – rather than from – the deceased.

Not all experts agree 'deviant' burials necessarily imply a belief in vampires. Historian and archaeologist David Barrowclough of the University of Cambridge in the UK penned a 2014 paper that argues other interpretations are just as valid as the notion of the vampire burial, if not more so, since some burials predate the idea of the unwelcome undead as we know it.

Here are some mysterious vampire burials from history. Read through, and judge for yourself.

The Vampire of Lugnano

In Lugnano, Italy, is a tragic 5th century CE cemetery. It's called La Necropoli dei Bambini – that is, the Cemetery of the Babies. That should give you some idea of who is buried there, and the reason for their gathering is equally distressing. None of the remains excavated from the cemetary are of children who lived past the age of 10. Curiously, they all died within the same short space of time.

The presence of Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest of the malaria-causing parasites, reveals a catastrophe: a sickness that swept the region and devastated the population, among which children are among the most vulnerable.

One burial in particular stands out as strange. The oldest of the interred, just 10 years old at time of death, was buried with a fist-sized rock lodged between their jaws, with tooth marks on the rock indicating it was placed deliberately. This has been seen in other vampire burials, and is interpreted as a measure preventing the dead from rising.

The soul, or anima, was thought to have exited the body through the mouth; stopping up the means of egress is thought to have been a measure to prevent it from re-entering.

Whichever way you look at it, though, the small bones uncovered in the Cemetery of the Babies can only tell a story of darkness and despair.

The Vampire of Venice

There may have been another reason for lodging a stone into the jaws of the dead, as seen in a burial in Venice in the 16th or 17th centuries. During this time, the bubonic plague tore through the city in multiple outbreaks, killing tens of thousands of its inhabitants.

A mass grave uncovered and excavated on the quarantine island of Lazzaretto Nuovo in 2006-2007 turned up the remains of a woman who had a brick sitting in her oral cavity. Anthropologists believed this to be a vampire burial, with the brick so placed to prevent the body from eating the corpses around it and regaining enough vitality to leave the grave and spread the pestilence further.

It's not entirely clear whether this particular burial was deliberately treated in this manner, though. A subsequent paper found that the brick could have fallen into the corpse's mouth as material settled over the body, her mouth falling open as the connective tissue decomposed.

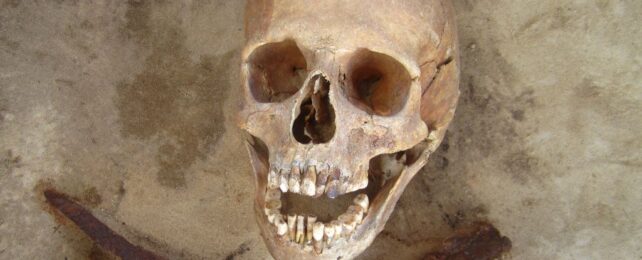

Vampire of Pień

One potentially bloody way to prevent the rise of the dead was found in Poland. In the village of Pień, in the 17th century, the grave of a young woman suggests that those who buried her were deeply fearful of her becoming vertical again.

Across her neck was lodged a sickle, a bladed tool used for harvesting. And it was not placed flat, either – the edge of the blade was facing towards her; if the body were to ever move from its position, its neck would be sliced from ear to ear. In addition, around her big toe was a triangular padlock, a ceremonial object to prevent the deceased from returning to the land of the living.

Odd accoutrements aside, the young woman was buried with care. Her head, clad in a silk bonnet woven with gold, was placed on a pillow. Although her mourners may have feared her return after death, she certainly seems to have been cherished prior to her death sometime between the ages of 17 and 21.

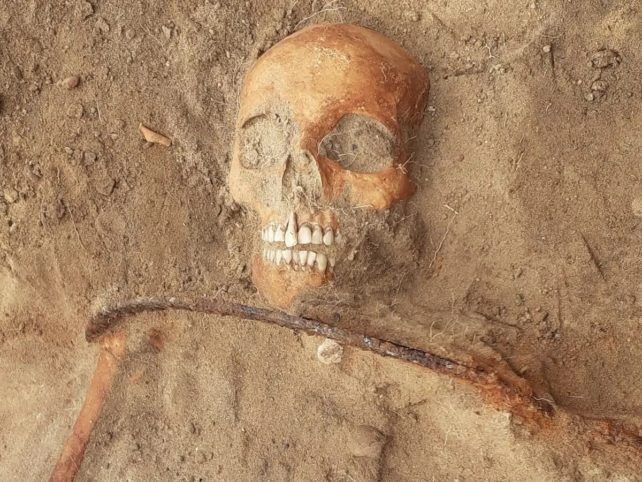

Polish vampires

As noted above, vampire burials in Poland seem to have been particularly prevalent. A 2014 paper investigates six such burials amid 285 individuals discovered in a 17th and 18th century cemetery in the northern town of Drawsko.

Of these burials, five had a sickle lodged across the throat or abdomen as a disincentive to rise, while two had a large stone placed across the throat, although whether that was to prevent rising, to prevent the ability to eat, or to perform both functions is unclear.

These burials, the researchers found, were local members of the Drawsko community, and hadn't been kept apart from the others interred in the cemetery. The researchers believe that the deaths may have been the result of a cholera outbreak running rampant at the time.

"Individuals ostracized during life for their strange physical features, those born out of wedlock or who remained unbaptized, and anyone whose death was unusual in some way – untimely, violent, the result of suicide, or even as the first to die in an infectious disease outbreak – all were considered vulnerable to reanimation after death," they wrote in their paper.

Whether outcast or ill, scapegoat or pure oddity, unusual graves throughout the ages have hinted at a complex relationship we humans have with our loved ones once they've left us behind.