For centuries, the faithful and the curious have crowded to gaze up at the Sistine Chapel's ceiling in awe of Michelangelo Buonarroti's reimagining of scenes from Genesis.

Few, if any, may have noticed that one among the 300 figures was destined to soon die.

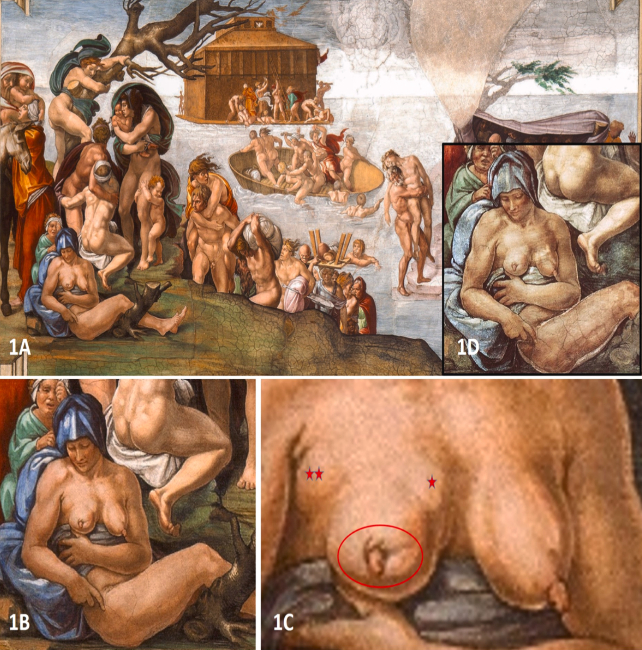

A detailed investigation of a woman's breast painted on the second span of the vault has concluded its unusual features represent advanced breast cancer, a disease the artist not only would have been aware of, but intentionally chose to depict.

The international team of experts provided insights from a variety of disciplines, combining their knowledge of art history, medicine, and genetics to diagnose the state of health of a fictitious, semi-naked woman in a scene depicting the biblical flood and propose reasons for her presence.

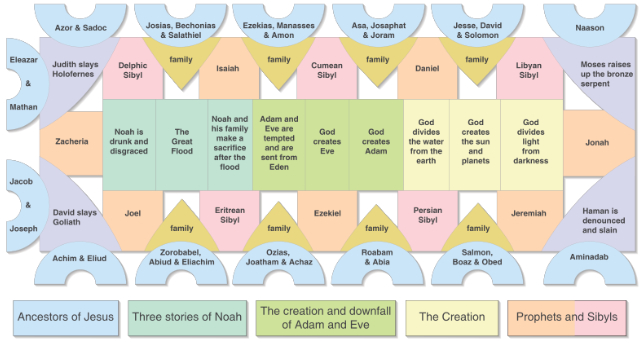

Commencement on the chapel ceiling began in 1508 on order by Pope Julius II, taking four years in total to complete its numerous scenes from the Old Testament, images of prophets, and representations of other noted biblical events.

Michelangelo was a seasoned artist in his thirties when he reluctantly agreed to take on the immense task, bringing years of experience sculpting anatomy and capturing extraordinary levels of detail in his subjects.

With that in mind, observations of what appeared to be a deformity in the breast of one of the figures couldn't be easily dismissed as an accidental smudge from an amateur hand.

To the lay viewer, the woman is just one in a crowd of fatigued bodies escaping the rising waters sent by God to cleanse the world of sin. To art historians, the blue color of the headscarf is a sign of her married status, her finger gesturing at the earth suggesting her return to dust was imminent.

Medical experts focused their attention on the right breast, shaped by age and motherhood, with a shading indicative of retracted skin around the areolar region, and subtle swellings in the upper quarter and near the armpit. Were it a photograph in a case file, the characteristics would all be strongly suggestive of breast cancer.

Breast cancer in relatively young subjects as this could be explained by an inheritance of high-risk genes, some of which have been traced back centuries in Europe.

Comparing the details with features of the woman's other breast, along with those on numerous other figures in the painting, the team was confident the design was unique enough to be intentional.

Over the centuries, the ceiling has undergone numerous interventions and restorations in an attempt to preserve its color and detail, including a major rework in the late 20th century. Comparisons of photographs taken of the scenes in the past make it clear the original shape and shading of the breasts haven't changed substantially.

Michelangelo was no stranger to death and disease. Unlike many contemporary artists who honed their craft by studying living models, he had participated in dissections since his teens, gaining an appreciation of how the body operated on a mechanical level.

The researchers refute suggestions the artist authentically copied the pathology from a model with breast cancer – or even a male model transformed with ill-fitting anatomy.

"Michelangelo did not resort to a living model (or living models either male or female) when depicting the story of the Genesis," the team writes.

"No realistic portraits are presented in the scene. It is rather the composition of an idea based upon the story of the Bible with idealized faces and bodies."

This may not even be Michelangelo's only depiction of the disease. Years later he would carve a feminine representation of the night for the tomb of Giuliano de' Medici with a similarly distorted breast, catching the eye of oncologists back in 2000.

If inflictions of breast cancer were subtly painted into the masterpiece with consideration, what would be the purpose?

"The representation of a probable breast cancer is linked to the concept of the impermanence of life and has the significance of punishment," the researchers suggest.

An embodiment of sin in the form of a deadly disease, the symbol in the Sistine Chapel has gone unappreciated by many for so long. Centuries on, Michelangelo's unique gift for understanding the human body continues to astonish.

This research was published in The Breast.