Determining the passage of time in our world of ticking clocks and oscillating pendulums is a simple case of counting the seconds between 'then' and 'now'.

Down at the quantum scale of buzzing electrons, however, 'then' can't always be anticipated. Worse still, 'now' often blurs into a haze of vagueness. A stopwatch simply isn't going to work for some scenarios.

A potential solution could be found in the very shape of the quantum fog itself, according to a 2022 study by researchers from Uppsala University in Sweden.

Their experiments on the wave-like nature of something called a Rydberg state revealed a novel way to measure time that doesn't require a precise starting point.

Rydberg atoms are the over-inflated balloons of the particle kingdom. Puffed up with lasers instead of air, these atoms contain electrons in extremely high energy states, orbiting far from the nucleus.

Of course, not every pump of a laser needs to puff an atom up to cartoonish proportions. In fact, lasers are routinely used to tickle electrons into higher energy states for a variety of uses.

In some applications, a second laser can be used to monitor the changes in the electron's position, including the passing of time. These 'pump-probe' techniques can be used to measure the speed of certain ultrafast electronics, for instance.

Inducing atoms into Rydberg states is a handy trick for engineers, not least when it comes to designing novel components for quantum computers. Needless to say, physicists have amassed a significant amount of information about the way electrons move about when nudged into a Rydberg state.

Being quantum animals, though, their movements are less like beads sliding about on a tiny abacus, and more like an evening at the roulette table, where every roll and jump of the ball is squeezed into a single game of chance.

The mathematical rule book behind this wild game of Rydberg electron roulette is referred to as a Rydberg wave packet.

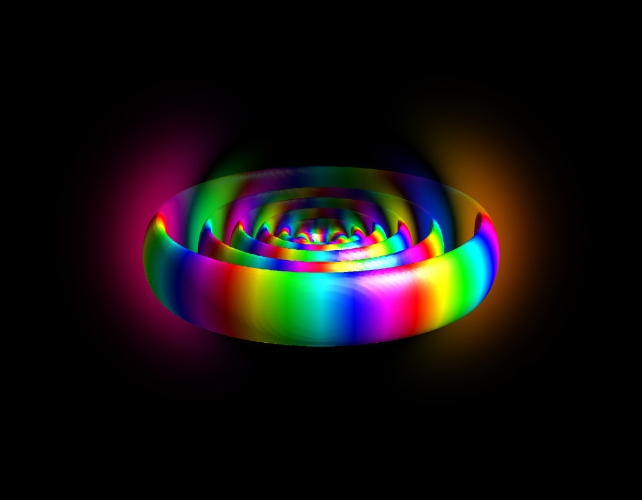

Just like actual waves, having more than one Rydberg wave packet rippling about in a space creates interference, resulting in unique patterns of ripples.

Throw enough Rydberg wave packets into the same atomic pond, and those unique patterns will each represent the distinct time it takes for the wave packets to evolve in accordance with one another.

It was these very 'fingerprints' of time that the physicists behind this set of experiments set out to test, showing they were consistent and reliable enough to serve as a form of quantum timestamping.

Their research involved measuring the results of laser-excited helium atoms and matching their findings with theoretical predictions to show how their signature results could stand in for a duration of time.

"If you're using a counter, you have to define zero. You start counting at some point," physicist Marta Berholts from the University of Uppsala in Sweden, who led the team, explained to New Scientist in 2022.

"The benefit of this is that you don't have to start the clock – you just look at the interference structure and say 'okay, it's been 4 nanoseconds.'"

A guidebook of evolving Rydberg wave packets could be used in combination with other forms of pump-probe spectroscopy that measure events on a tiny scale, when now and then are less clear, or simply too inconvenient to measure.

Importantly, none of the fingerprints require a then and now to serve as a starting and stopping point for time. It'd be like measuring an unknown sprinter's race against a number of competitors running at set speeds.

By looking for the signature of interfering Rydberg states amid a sample of pump-probe atoms, technicians could observe a timestamp for events as fleeting as just 1.7 trillionths of a second.

Future quantum watch experiments could replace helium with other atoms, or even use laser pulses of different energies, to broaden the guidebook of timestamps to suit a broader range of conditions.

This research was published in Physical Review Research.

An earlier version of this article was published in October 2022.