The tree of life is often more like a vine that snakes back on itself, with tendrils briefly embracing before they reach for the sky or wither into nothing.

While much has been said about the Neanderthal and human branches of humanity, it's becoming increasingly clear our past has had frequent encounters with another close relative known as the Denisovans (pronounced duh-nee-suh-vns).

A recently published review of the existing research on Denisovan DNA by Trinity College Dublin population geneticists Linda Ongaro and Emilia Huerta-Sanchez brings us up to date on how our own biology has been influenced by the history of a people we still know so very little about.

According to their interpretation of the evidence, a number of Denisovan populations that were adapted to environments across the Asian continent and beyond passed their genes to our own recent ancestors on multiple occasions, bestowing us with a selection of their advantages just as Neanderthals have done.

"It's a common misconception that humans evolved suddenly and neatly from one common ancestor, but the more we learn the more we realize interbreeding with different hominins occurred and helped to shape the people we are today," says Ongaro, first author of the recent study.

Compared with the century or two that scientists have spent examining Neanderthal remains, graves, and artifacts, our academic acquaintance with the Denisovans is remarkably recent, and limited. A mere handful of teeth and bones belonging to these extinct relatives have been recovered over recent decades.

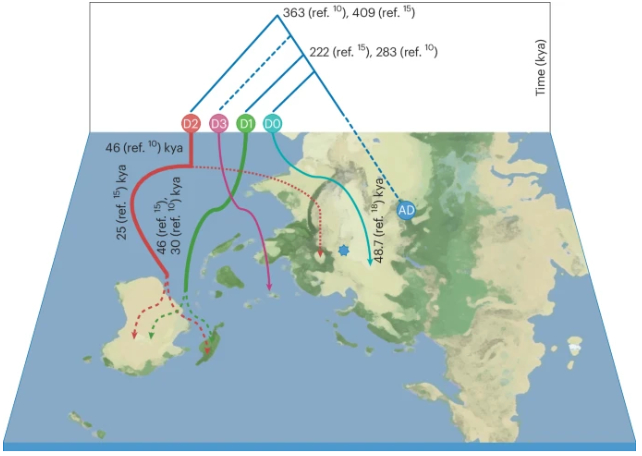

Following a series of genetic analyses that began with a young female's fingerbone in 2010, the remains are now understood to belong to a previously undescribed hominin group that became genetically distinct from Neanderthals around 400,000 years ago – most likely a few hundred thousand years after Neanderthals became distinct from our own ancestors.

Our understanding of the range, culture, and adaptations of the Denisovans has been building slowly over the years, hinting at a rich diversity of humans with a genetic legacy that stretches from Siberia to South East Asia and across Oceania to even the Americas.

"By leveraging the surviving Denisovan segments in modern human genomes scientists have uncovered evidence of at least three past events whereby genes from distinct Denisovan populations made their way into the genetic signatures of modern humans," says Ongaro.

Among extant genes known to have originated among Denisovans are sequences common in Tibetan populations that help the body cope with relatively low amounts of oxygen, DNA that gives Papuan immunity a boost, and genes found among Inuit lineages that influence the burning of fats to cope better with the cold.

These join the diverse genes swapped through frequent interactions with Neanderthals that have helped some of us weather pandemics, influenced our appearance, and even shaped our brains.

Ongaro and Huerta-Sanchez's review serves to highlight not just what we've learned, but just how little we know about the way distinct pockets of modern humans have been changed by encounters with these extinct relatives.

"There are numerous future directions for research that will help us tell a more complete story of how the Denisovans impacted modern day humans, including more detailed genetic analyses in understudied populations, which could reveal currently hidden traces of Denisovan ancestry," says Ongaro.

This research was published in Nature Genetics.