A "provocative" new piece in Nature has proposed a whole new group of ancient humans – cousins of the Denisovans and Neanderthals – that once lived alongside Homo sapiens in eastern Asia more than 100,000 years ago.

The brains of these extinct humans, who probably hunted horses in small groups, were much bigger than any other hominin of their time, including our own species.

Paleoanthropologist Xiujie Wu from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and anthropologist Christopher Bae from the University of Hawai'i have called this new group the Juluren, meaning "large head people".

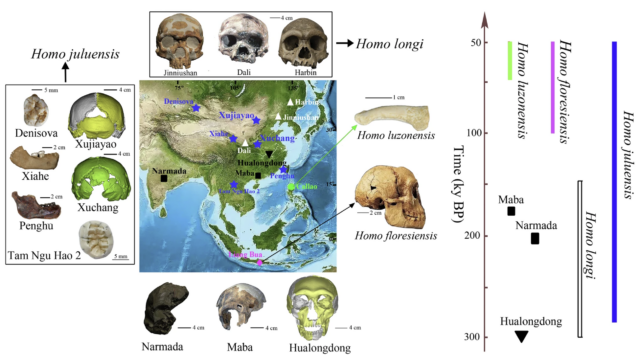

In the past, some scientists have attributed the Juluren (Homo juluensis) fossils to Denisovans (pronounced duh-nee-suh-vns), who are a group of ancient humans, related to Neanderthals, that once lived alongside and even mated with modern humans in parts of Asia.

But Wu and Bae have taken a closer look, and they say the features of some fossils found in China cannot be easily assigned to modern humans, Neanderthals, Denisovans, or Homo erectus, the hominins that came before our own species.

Their mosaic of traits hint at a mix of ancestry between various hominin groups, all living in the same regions of Asia between 300,000 and 50,000 years ago.

"Collectively, these fossils represent a new form of large brained hominin," concluded Wu and Bae in the journal PaleoAnthropology earlier this year.

"Although we started this project several years ago, we did not expect being able to propose a new hominin (human ancestor) species and then to be able to organize the hominin fossils from Asia into different groups," says Bae.

Anthropologist John Hawks who was not involved in the research calls Bae and Wu's recent commentary "provocative", and in his blog earlier this year, he reviewed their study and agreed that while evidence of the Juluren is limited, the human record in Asia is "more expansive than most specialists have been assuming."

Until very recently, all hominin fossils found in China that did not match Homo erectus or Homo sapiens were lumped together. Compared to hominin fossils in Africa and Europe, the human fossil record in eastern Asia is poorly differentiated and described.

"Calling all these groups by the same name makes sense only as a contrast to recent humans, not as a description of their populations across space and time," writes Hawks on his blog.

"I see the name Juluren not as a replacement for Denisovan, but as a way of referring to a particular group of fossils and their possible place in the network of ancient groups."

In the last two decades alone, the human family tree has gone from a carefully pruned bonsai to a bushy tangled mess, and trying to tease apart and name all the various branches is proving quite the challenge.

Every few years, it seems, new lineages pop up, weaving in and out with other branches of life before inexplicably coming to an end.

In 2003, scientists discovered Homo floresiensis – the smallest known species of human who lived at least 100,000 years ago on an island in Indonesia.

In 2007, archaeologists discovered Homo luzonensis – a completely new hominid species from 67,000 years ago – in the Philippines.

In 2010, DNA analysis revealed the existence of ancient Denisovans in what is now Russia, near the border of Kazakhstan and Mongolia.

In 2018, paleoanthropologists were given a fossil from northeastern China that turned out to be an extinct species of archaic human, possibly related to the Denisovans. Only in 2021, did scientists formally designate the species as Homo longi.

Now, Wu and Bae want to introduce Homo juluensis to the revolution.

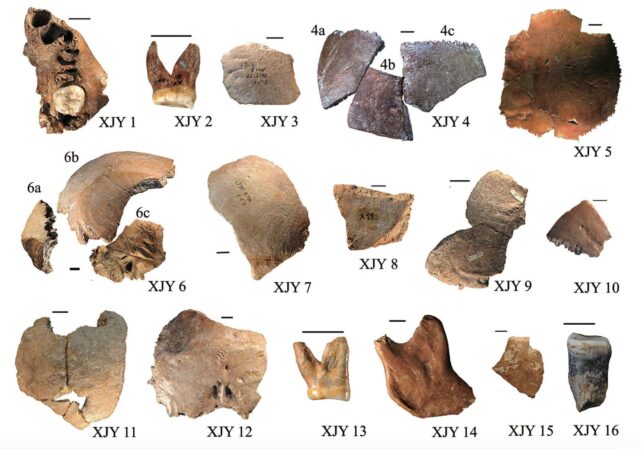

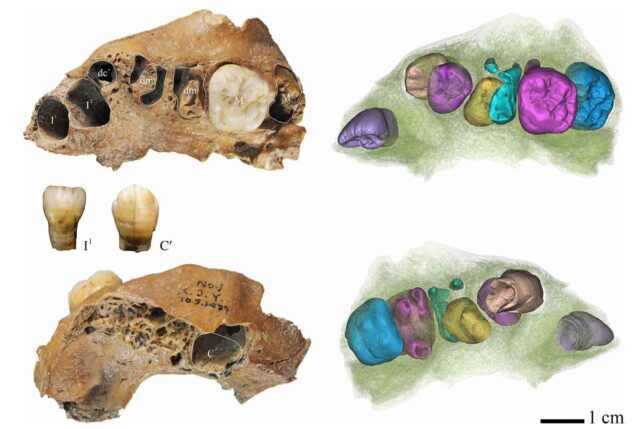

The various fossils belonging to H. juluensis come from the face and jaw, and they apparently show classic Neanderthal-like dental characteristics. But some traits are not seen in other known hominins, including the Denisovans.

"It is becoming increasingly clear that [in] the eastern Asian hominin fossils… a greater degree of morphological variation is present than originally assumed or anticipated," write Wu and Bae.

In 2023, for instance, scientists found a hominin fossil in Hualongdong, China, unlike any other human fossil on record. It's not a Denisovan, or a Neanderthal, and it does not fit neatly into H. juluensis or H. longi.

Wu and Bae say this is a good example "of the intricacy of the human evolutionary record."

"If anything," they write, "the eastern Asian record is prompting us to recognize just how complex human evolution is more generally and really forcing us to revise and rethink our interpretations of various evolutionary models to better match the growing fossil record."

The commentary was published in Nature Communications.