A plant that lived 47 million years ago in what is now Utah is like nothing that lives on planet Earth today.

The discovery of new fossils reveals that a species first found in 1969 is not a member of the ginseng family, as scientists had initially speculated. Rather, the entire family of the newly named Othniophyton elongatum is extinct, suggesting that the history of flowering plants is more complicated than we knew.

Othniophyton elongatum specimens were first excavated from the Green River Formation in Utah, a particularly rich fossil bed dating back to the Eocene. Generally speaking, paleobotanists assume that any plant fossils dating from the beginning of the Cenozoic 65 million years ago must be related to plants that are alive today, and Othniophyton elongatum was no exception.

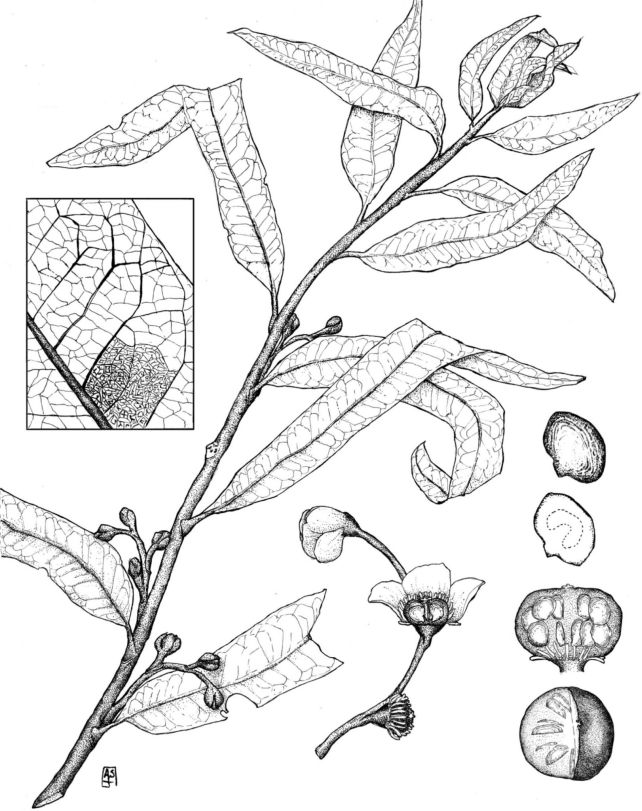

The paleobotanist who initially studied the fossils, Harry MacGinitie, named it Oreopanax elongatum – placing it into a genus of shrubs under a family umbrella that includes ginseng, angelica, and ivy. After a close study of the leaves, scientists thought that they may be compound leaves, made up of many smaller leaves, like some ginseng family plants. Oreopanax xalapensis is one example.

And that could have been that… until the discovery of another set of 47-million-year-old plant fossils came to light. It had leaves just like the 1969 fossils – but that wasn't all.

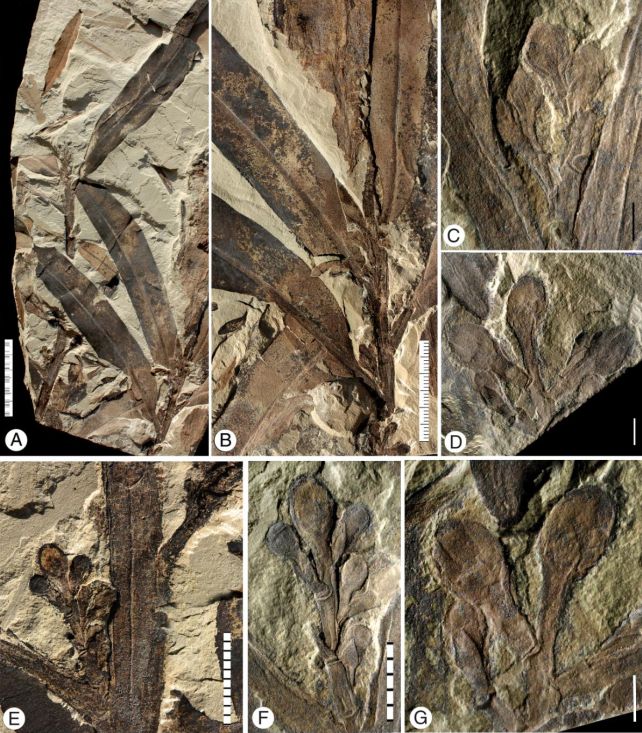

"This fossil is rare in having the twig with attached fruits and leaves," explains paleobotanist Steven Manchester of the Florida Museum of Natural History. "Usually those are found separately."

With so many more components of the plant in hand, Manchester and his colleagues set about trying to learn more about Oreopanax elongatum. But the more they looked at their new fossils, the more they realized that the Eocene plant had nothing in common with the genus Oreopanax, or the Araliaceae family to which it belongs.

The leaves, directly attached to the twig, were the first clue. They were not compound leaves, as initially thought, back in the 1960s. And looking at the berries, the plant just got even more puzzling. The strange set of features displayed by the fossil matched no living flowering plants at all, the researchers found.

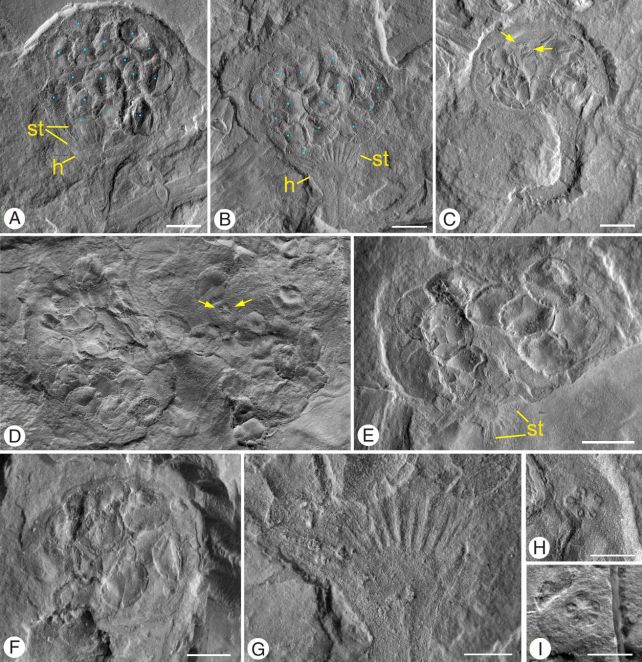

A breakthrough arrived with a new microscopy station installed at the museum. This allowed the researchers to look at the plant in much greater detail than they had been able to see before. They could look inside the berries to see the plant's seeds, and tease apart the minute details of the flowers.

One of the oddest observations Manchester and his colleagues made was that the plant's stamens – the male part of the reproductive system – had not fallen off as the berries developed.

"Normally we don't expect to see that preserved in these types of fossils, but maybe we've been overlooking it because our equipment didn't pick up that kind of topographic relief," Manchester says.

"Usually, stamens will fall away as the fruit develops. And this thing seems unusual in that it's retaining the stamens at the time it has mature fruits with seeds ready to disperse. We haven't seen that in anything modern."

The next step was to try to match it to Cenozoic-era plants on the fossil record. Once again, the researchers came up empty. There were just no known plants similar enough to what they were looking at. Even where similarities could be found with other plants, there were too many differences to make a link.

We just don't know where this plant sits in relation to other plants. It's the most similar to the Caryophyllales order, but there are too many differences.

The researchers renamed the extinct plant Othniophytum elongatum – from the Greek and Latin for "elongated alien plant" – and concluded that it likely belongs to a family of plants that no longer exists on Earth.

This means that paleobotanists have a new tool for studying how plants diversified, adapted, and changed – and, perhaps, which strategies may have been less effective at survival across millions of years of a changing world.

And it's a bit of a cautionary tale, too, not to let biases and assumptions overtake the evidence.

"There are many things for which we have good evidence to put in a modern family or genus, but you can't always shoehorn these things," Manchester says.

The research has been published in Annals of Botany.