A medical technology company in Australia is aiming for a world-first: it wants to launch a blood test for endometriosis (sometimes called 'endo' for short) within the first half of this year.

In a recent peer-reviewed trial, its novel test proved 99.7 percent accurate at distinguishing severe cases of endometriosis from patients without the disease but with similar symptoms.

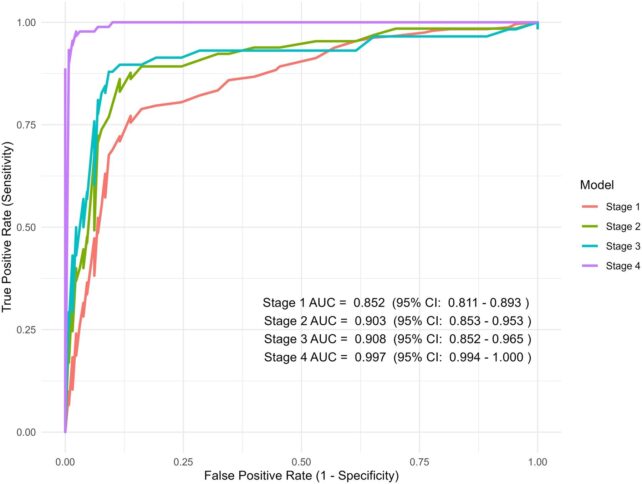

Even in the early stages of the disease, when blood markers may be harder to pick out, the test's accuracy remained over 85 percent.

The company behind the patent, Proteomics International, says it is currently adapting the method "for use in a clinical environment," with a target launch date in Australia for the second quarter of this year.

The test is called PromarkerEndo.

"This advancement marks a significant step toward non-invasive, personalized care for a condition that has long been underserved by current medical approaches," managing director of Proteomics International Richard Lipscombe said in a press release from December 30.

Endometriosis is a common inflammatory disease that occurs when tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows in other parts of the body, forming lesions. The disease can be very painful, and yet the average patient often suffers debilitating symptoms for up to seven years before they are properly diagnosed.

While there are numerous reasons for such a long delay, symptoms of endometriosis are often highly variable, unpredictable, difficult to measure or describe, and dismissed or overlooked by doctors.

Today, the only definitive way to diagnose endometriosis is via keyhole surgery called a laparoscopy, which is expensive, invasive, and carries risks.

Proteomics International is hoping to change that.

In collaboration with researchers at the University of Melbourne and the Royal Women's Hospital, the company compared the bloodwork data from 749 participants of mostly European descent.

Some had endometriosis and others had symptoms that were similar to endo but without the lesions. All participants had a laparoscopy to confirm the presence or absence of the disease.

Sifting through the bloodwork, researchers ran several different algorithms to figure out which proteins in the blood were best at predicting endometriosis of varying stages.

Building on previous research, a panel of 10 proteins showed a "clear association" with endometriosis.

For years now, scientists have investigated possible blood biomarkers of endometriosis to see if they could differentiate between those who have endo and those who do not. Similar to cancerous tumors, endo lesions can establish their own blood supply, and if cervical cancer can be diagnosed via a blood test, it seemed possible that endometriosis could be, too.

So far, however, no standalone test exists. Some biomarkers have been identified, but their effectiveness as a diagnostic test rarely gets above 90 percent.

Gynaecologist Peter Rogers from the University of Melbourne said he and his team's work is "a significant step towards solving the critical need for a non-invasive, accurate test that can diagnose endometriosis at an early stage as well as when it is more advanced."

But there's still more to be done. It's possible that some of the control participants in the trial were actually undiagnosed positive cases, influencing the apparent accuracy of the test. Researchers are now refining the algorithm on further datasets.

Proteomics International claims patents for PromarkerEndo are "pending in all major jurisdictions," starting first in Australia.

It remains to be seen if the company's blood test lives up to the hype and is approved by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). But that's not outside the realm of possibility.

In November of 2023, some researchers predicted that a "reliable non-invasive biomarker for endometriosis is highly likely in the coming years."

Perhaps this is the year.

The study was published in Human Reproduction.