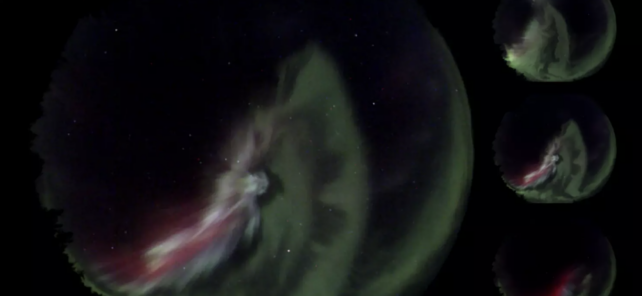

A ground-based observing facility tasked with recording the flare of the northern lights has captured images of an inexplicable pale grey glow amid the streaks of green and red, providing researchers with new details into the mystery.

While the bright intrusion itself has been seen before by sky watchers in the far north, nobody has had a good explanation for its appearance.

Making use of the new spectral data, a team of researchers led by scientists at the University of Calgary in Canada might at last have a solution in sky chemistry, likening the bleached islands of white and grey to the recently described meteorological oddity with the relatively whimsical name 'STEVE'.

"You'd see this dynamic green aurora, you'd see some of the red aurora in the background and, all of a sudden, you'd see this structured – almost like a patch – grey-toned or white toned-emission connected to the aurora," says Emma Spanswick, a physicist at the University of Calgary.

"So, the first response of any scientist is, 'Well, what is that?'"

For the most part, the Sun keeps its swirling soup of charged particles contained by gravity and a tangled net of magnetic fields. Every now and then forces align that see tiny amounts of plasma squirt free in our direction.

Earth's magnetic cage steers most of this energetic shower into space, but in extreme cases a fraction of the solar particles collide with the atmosphere, causing its molecules to glow in a rich palette of color defined by their elemental make-up and concentration.

While green and pink hues are expected in these luminescent displays as the glow produced by oxygen and nitrogen at different altitudes, occasional splashes of white and grey have had no simple explanation.

Auroras aren't the only show in town, however. Our planet's atmosphere can shed light through other energetic processes, some a little more complex than others. Plain old sunlight can cause molecules to fall apart and recombine, for example, spilling a faint light that can be seen in Earth's shadow known as nightglow.

Several years ago, a greyish-mauve sweep of light, affectionately named Steve by aurora enthusiasts (retrospectively transformed into an acronym for Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement), presented physicists with a mystery to solve.

Possessing a continuum of wavelengths that blended to form tinges of white and grey, STEVE's structure and color distinguished it from conventional auroras. While researchers continue to make headway into determining what's behind this unusual meteorological phenomenon, the glow's pale highlights are assumed to be somewhat akin to nightglow, a result of some kind of chemical rearrangement.

"There are similarities between what we're seeing now and STEVE," says Spanswick. "STEVE manifests itself as this mauve or grey-toned structure.

"To be honest, the elevation of the spectrum between the two is very similar but this, because of its association with dynamic aurora, it's almost embedded in the aurora. It's harder to pick out if you were to look at it, whereas STEVE is separate from the aurora – a big band crossing the sky."

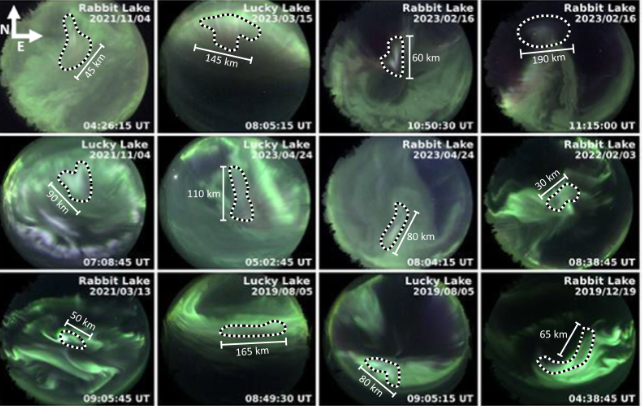

Fortunately researchers don't need to squint into the sky night after night in the hopes of catching sight of unusual blemishes in the aurora. The recently deployed high-resolution sky-imaging observatory called the Transition Region Explorer provides a record of auroras in color profiles calibrated to provide reliable spectral data, allowing the research team to analyze the blend of wavelengths making up the white light for clues on its production.

The researchers determined the patches range in size from tens to hundreds of kilometers, appear within active auroras, and are likely to be caused by something in the display releasing heat that in turn triggers chemical reactions capable of emitting a continuum of electromagnetic wavelengths.

Exactly what is breaking down and recombining to glow is only hypothetical at this stage, but the entire process could represent a novel chain of events tangentially linked to auroras.

Modeling the layers of the atmosphere in laboratory experiments and collecting more examples of the mysterious white patches of light could add vital details and new complexities to the greatest show in the sky.

This research was published in Nature Communications.