Astronomers have found two planets around two separate stars that are succumbing to their stars' intense heat. Both are disintegrating before our telescopic eyes, leaving trails of debris similar to a comet's. Both are ultra-short-period planets (USPs) that orbit their stars rapidly.

These planets are a rare sub-class of USPs that are not massive enough to hold onto their material. Astronomers know of only three other disintegrating planets.

USPs are known for their extremely rapid orbits, some completing an orbit in only a few hours. Since they're extremely close to their stars, they're subjected to intense heat, stellar radiation, and gravity.

Many USPs are tidally locked to their star, turning the star-facing side into an inferno. USPs seldom exceed two Earth radii, and astronomers think that about 1 in 200 Sun-like stars has one. They were only discovered recently and are pushing the boundaries of our understanding of planetary systems.

There are plenty of unanswered questions about USPs. Their formation mechanism is unclear, though they likely migrated to their positions rather than formed there. They're difficult to observe because of their proximity to their stars, making questions about their structures difficult to answer.

Fortunately, two separate teams of researchers have spotted the two disintegrating USPs. As they spill their contents out into space in tails, they're giving astronomers an opportunity to see what's inside them.

The new observations are in two new papers available at the pre-press site arxiv.org. One is "A Disintegrating Rocky Planet with Prominent Comet-like Tails Around a Bright Star." The lead author is Marc Hon, a postdoctoral researcher at the MIT TESS Science Office. This paper is referred to hereafter as the MIT study.

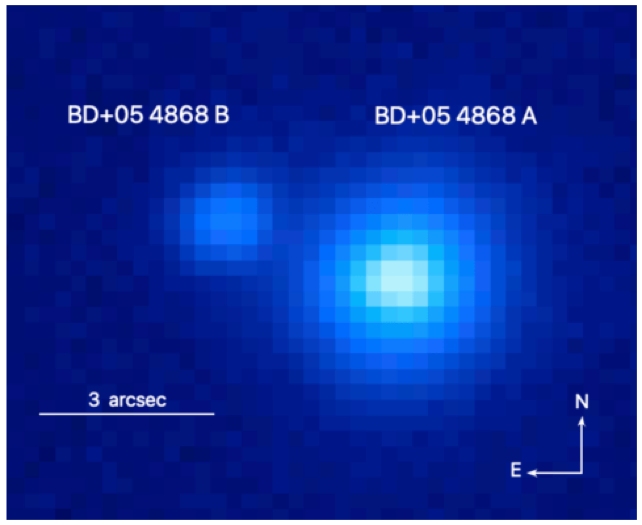

"We report the discovery of BD+054868Ab, a transiting exoplanet orbiting a bright K-dwarf with a period of 1.27 days," the authors write. The TESS spacecraft found the planet, and its observations "reveal variable transit depths and asymmetric transit profiles," the paper states.

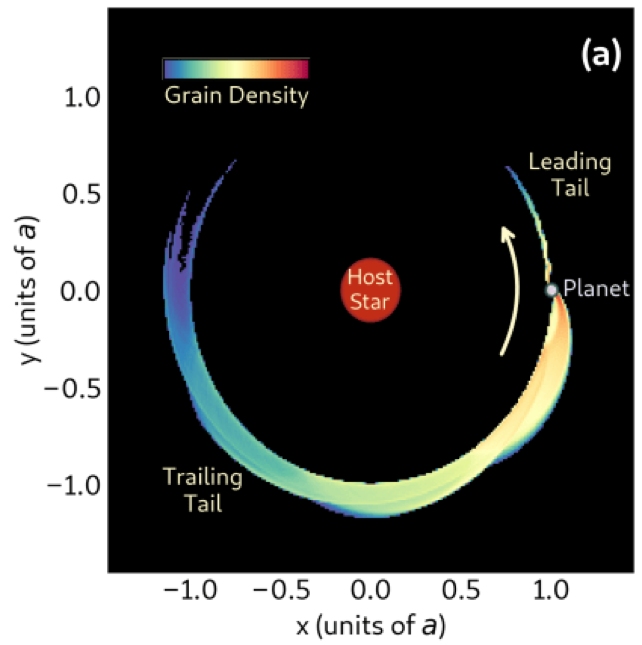

Those are characteristics of dust coming from the doomed planet and forming tails: one on the leading edge and one on the trailing edge. Dust particle size in each tail is different, with the leading trail containing larger dust and the trailing tail containing finer grains.

"The rate at which the planet is evaporating is utterly cataclysmic, and we are incredibly lucky to be witnessing the final hours of this dying planet','"

Marc Hon, MIT TESS Science Office

"The disintegrating planet orbiting BD+05 4868 A has the most prominent dust tails to date, "said lead author Hon. "The dust tails emanating from the rapidly evaporating planet are gigantic. Its length of approximately 9 million km encircles over half the planet's orbit around the star every 30 and a half hours," he added.

The MIT study shows that the planet is losing mass at the rate of 10 Earth masses of material per billion years. Since the object is probably only roughly the size of Earth's Moon, it will be totally destroyed in only a few million years.

"The rate at which the planet is evaporating is utterly cataclysmic, and we are incredibly lucky to be witnessing the final hours of this dying planet," said Hon.

The host star is probably a little older than the Sun and has a companion red dwarf separated by about 130 AU. The authors think that the planet is a great candidate for follow-up studies with the JWST. Not only is the star bright, but the transits are deep. Because of the leading and trailing tails, the transits can last up to 15 hours.

"The brightness of the host star, combined with the planet's relatively deep transits (0.8?2.0%), presents BD+054868Ab as a prime target for compositional studies of rocky exoplanets and investigations into the nature of catastrophically evaporating planets," they explain.

"What's also highly exciting about BD+05 4868 Ab is that it has the brightest host star out of the other disintegrating planets —about 100 times brighter than K2-22—establishing it as a benchmark for future disintegrating studies of such systems," said Avi Shporer, a Research Scientist at the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research and a co-author of the MIT paper.

"Prior to our study, the three other known disintegrating planets were around faint stars, making them challenging to study," he added.

The second paper is "A Disintegrating Rocky World Shrouded in Dust and Gas: Mid-IR Observations of K2-22b using JWST." The lead author is Nick Tusay, a PhD student at Penn State working in the Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds. This paper is hereafter referred to as the Penn State study.

"The effluents that sublimate off the surface and condense out in space are probably representative of the formerly interior layers convectively transported to the molten surface," the authors write.

In this work, astronomers were able to observe its debris with the JWST's MIRI and also with other telescopes. The observations show that the material coming from the USP is not likely to be iron-dominated core material. Instead, they're "consistent with some form of magnesium silicate minerals, likely from mantle material," the authors explain.

"These planets are literally spilling their guts into space for us, and with JWST we finally have the means to study their composition and see what planets orbiting other stars are really made of," said lead author Tusay.

We can't see what's inside the planets in our Solar System, though seismic waves and other observations give scientists a pretty good idea about Earth's interior. By examining the entrails coming from K2-22b, astronomers are learning not only about the planet but, by extension, about other rocky planets. The irony is that they're so far away.

"K2-22b has an asymmetric transit profile, as the planet's dusty cloud of effluents comes into view in front of the star, showing evidence of extended tails like a comet."

"It's a remarkable and fortuitous opportunity to

understand terrestrial planet interiors."Professor Jason Wright, Astronomy and Astrophysics, Penn State

"It's remarkable that directly measuring the interior of planets in the Solar System is so challenging—we have only limited sampling of the Earth's mantle, and no access to that of Mercury, Venus, or Mars—but here we have found planets hundreds of light years away that are sending their interiors into space and backlighting them for us to study with our spectrographs," said Jason Wright, Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics, co-author of the Penn State study, and Tusay's PhD supervisor.

"It's a remarkable and fortuitous opportunity to understand terrestrial planet interiors," he added.

While TESS discovered the disintegrating planet in the previous paper, Kepler found this one during its extended K2 mission. This one orbits its M-dwarf star in only 9.1 hours. Evidence of its tail is in the variability of its light curve. "The dramatic variability in lightcurve transit depth (0–1.3%) combined with the asymmetric transit shape suggests we are observing a transient cloud of dust sublimating off the surface of an otherwise unseen planet," the MIT paper states.

According to the authors, this could be the first time we've seen outgassing from a vaporizing planet. "The shorter MIRI wavelength features … may constitute the first direct observations of gas features from an evaporating planet," the paper states.

"Unexpectedly, the models that best fit these measurements seem to be ice-derived species (NO and CO2)," the authors write. Though the spectrum is broadly consistent with a rocky body, the presence of NO and CO2 is a bit of a curveball. These materials are more similar to icy bodies like comets rather than rocky planets.

"It was actually sort of a 'who-ordered-that?' moment," Tusay said about finding the icy features. For this reason, the researchers are eager to point the JWST at the planet again to obtain more and better data. Multiple pathways can generate these results, and only better data can help astronomers determine what's going on.

Though we're in the early days of observing planets like this one, scientists still have some expectations. These results defy those expectations since many expected to find only the iron-core remnants of these USPs.

"We didn't know what to expect," said Wright, who also co-authored an earlier study on how to use JWST to probe these exoplanetary tails. "We were hopeful they might still have their mantles, or potentially even crust material that was being evaporated. JWST's mid-infrared spectrograph MIRI was the perfect tool to check, because crustal, silicate mantle, and iron core materials would all transmit light in different ways that JWST could distinguish spectroscopically," Wright added.

Next, both teams of scientists hope to point the JWST at BD+05 4868 Ab from the MIT study. Its star is far brighter than the other stars known to host disintegrating USPs. A bright light source makes it much easier for the JWST to get stronger results.

"What's also highly exciting about BD+05 4868 Ab is that it has the brightest host star out of the other disintegrating planets —about 100 times brighter than K2-22—establishing it as a benchmark for future disintegrating studies of such systems," said Avi Shporer, a Research Scientist at the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research and a co-author of the MIT project.

"Prior to our study, the three other known disintegrating planets were around faint stars, making them challenging to study," he added.

When the JWST was launched, it wasn't aimed at observing disintegrating exoplanets. But this research shows off a new way of using the powerful telescope. Surprises like this are a part of every new telescope or observing effort, and researchers often look forward to them.

"The data quality we should get from BD+05 4868 A will be exquisite," said Shporer. "These studies have proven the validity of this approach to understanding exoplanetary interiors and opened the door to a whole new line of research with JWST."

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.