Previously thought to be an exclusively human skill, knowing when a friend could use a clue appears to be a talent we share with our primate cousins.

Researchers from Johns Hopkins University in Maryland observed bonobos (Pan paniscus) in a recent study point human researchers in the direction of treats the apes wished to gobble up.

These findings reveal cognitive connections between hominins that we didn't know existed, which potentially stretch back through millions of years to our common ancestors.

"The ability to sense gaps in one another's knowledge is at the heart of our most sophisticated social behaviors, central to the ways we cooperate, communicate, and work together strategically," says psychologist Chris Krupenye.

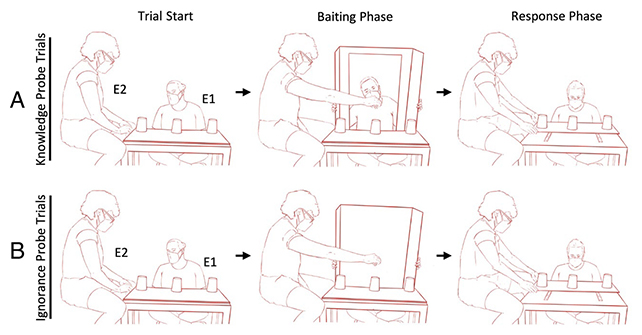

In the study's experiments, three male bonobos took turns to play a game with a researcher where treats were hidden under cups – sometimes while the researcher was watching, and sometimes not. If the treat was found, the ape could eat it.

The experiments showed the bonobos were more likely to gesture and to point more quickly at the cup hiding the treat when the researcher didn't know which cup hid the treat.

It seems like a simple action, but it's actually a profound insight into how our closest relatives can think and assess the perspective of others. Previous studies have observed apes warning their companions of danger, but these recent experiments remove elements of group mentality and survival instinct, exploring cognitive functions of individuals.

"What we've shown here is that apes will communicate with a partner to change their behavior, but a key open question for further research is whether apes are also pointing to change their partner's mental state or their beliefs," says psychologist Luke Townrow.

This theory of mind – the capacity to understand that others have mental states of belief or perspective that might be different to one's own – has typically been thought to distinguish human cognition from that of other animals.

We now have evidence that this ability in apes could be as flexible as it is in humans. Bonobos were see comprehending two things in their mind at once: both where the treat is hidden, and whether or not their partner knows where it's hidden. These findings can be followed up and expanded upon in future studies.

One question to look at in more detail could relate to the motivations of these bonobos: do they want to change their partner's mental state, or their behavior? We can expect more hidden treat experiments to follow.

"There are debates in the field about the capabilities of primates, and for us it was exciting to confirm that they really do have these rich capacities that some people have denied them," says Krupenye.

The research has been published in PNAS.