The Greenland shark likes to stick around, with some estimates suggesting a lifespan of more than 500 years – and a new study of the shark's DNA has given researchers vital clues to the secret of its longevity.

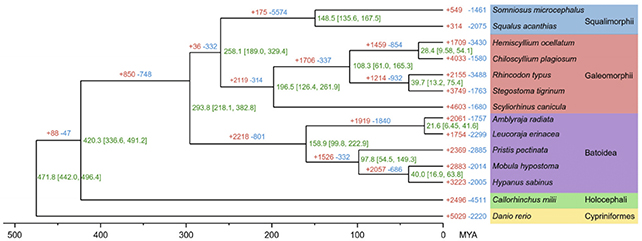

In the first detailed map of the Greenland shark's (Somniosus microcephalus) genome, researchers led by the University of Tokyo found genetic traits that protect against cancer, reduce inflammation, and help boost DNA repair.

Half a millennium is a considerable timespan, when you consider there might be Greenland sharks swimming around today that were born in the age of Galileo and Shakespeare. The findings could aid in future research into long and healthy living.

"These genomic analyses offer new insights into the molecular basis of the exceptional longevity of the Greenland shark and highlight potential genetic mechanisms that could inform future research into longevity," write the researchers in their paper.

The researchers collected tissue samples from a captured female Greenland shark, before releasing it back into the wild. Using high-fidelity sequencing, the team managed to identify 86.5 percent of the expected shark protein-coding genome.

There were more copies of genes promoting DNA repair and immune function in this shark than in shorter-lived species. The same was true for genes managing NF-κB signaling – which is linked to keeping cells intact and functioning, and reducing inflammation.

Mutations in genes linked to stopping cancer growth and spread appear to play a role in the shark's longevity too, the researchers found.

"We propose that the classical NF-κB signaling pathway is crucial for the exceptional longevity of S. microcephalus, as it regulates cell proliferation, migration, DNA repair, apoptosis, and immune response, which are all closely linked to inflammation, cancer, and autoimmune diseases," write the researchers.

These impressive fish can grow to lengths of over 6 meters (almost 20 feet) and weigh upwards of 1,000 kilograms (2,205 pounds). They don't reach reproductive maturity until the grand old age of 150 years – which makes them vulnerable to environmental pressures and human activity.

A deeper understanding of the shark's genome should reveal more about S. microcephalus and how it lives, and from there help us protect the species.

The implications of the study go way beyond sharks too: learning the genetic basis of its long life could yield insights that improve our own health and life expectancy.

"Future research should involve sequencing multiple individuals from various marine regions to elucidate global population dynamics in greater detail," write the researchers.

"The genome assembly we have constructed will undoubtedly serve as a crucial reference sequence for future studies."

The research hasn't yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, but is available on the preprint server bioRxiv.