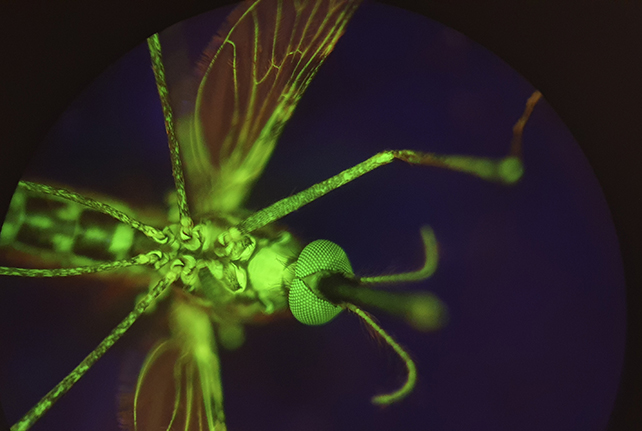

Scientists have a radical new plan for controlling mosquito numbers and fighting malaria: lacing human blood with a drug that's poisonous for the insects, so sucking on this blood marks their last meal.

The drug in question is nitisinone, and a proof-of-concept study led by a team from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the UK found that it could be deadly to mosquitoes at a low dose in human blood.

When mosquitoes fed on the blood of three people who were already taking nitisinone to treat a genetic disorder, the insects died within 12 hours.

Nitisinone already has regulatory approval for treating certain rare, inherited diseases. It works by blocking the production of a specific protein, which leads to reduced toxic disease byproducts in the human body. But when mosquitoes drink blood with nitisinone, they quickly die.

"One way to stop the spread of diseases transmitted by insects is to make the blood of animals and humans toxic to these blood-feeding insects," says microbiologist Lee R. Haines from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

"Our findings suggest that using nitisinone could be a promising new complementary tool for controlling insect-borne diseases like malaria."

The treatment is still very much a proof-of-concept idea, and enthusiasm should be tempered by initial results from other antiparasitic drugs that can kill insects vital to ecosystems, and which may not actually reduce malaria rates.

In previous research, nitisinone does not seem to kill other vital insects that have pollinating roles in ecosystems, but its wider ecological impacts are not well studied, and there's a chance of insecticide resistance becoming a problem in the future if the mosquito-killing meds are incorporated into "mass drug administration programs", as the authors of the study suggest.

The researchers tested the effects of nitisinone-filled blood on mosquitoes, as well as using math models to figure out the impact of different doses on simulated human populations. They found the drug was effective at killing mosquitoes of all ages – including the older insects that are more likely to be carrying malaria.

Antiparasitic drugs like this aren't a new idea, and the team compared nitisinone against ivermectin, which is already used as a potential tool to kill off mosquitoes as they feed.

While ivermectin given to humans or cows can kill mosquitoes at lower concentrations than nitisinone, the new drug acts more quickly, often within a day. It also sticks around in human blood for a longer time, making it more likely that mosquitoes will come into contact with it.

"We thought that if we wanted to go down this route, nitisinone had to perform better than ivermectin," says parasitologist Álvaro Acosta Serrano from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. "Indeed, nitisinone performance was fantastic."

"It has a much longer half-life in human blood than ivermectin, which means its mosquitocidal activity remains circulating in the human body for much longer. This is critical when applied in the field for safety and economical reasons."

Unlike ivermectin, nitisinone does not target the nervous system, so it is less neurotoxic. What's more, studies indicate that ivermectin kills other insects.

Malaria is still responsible for more than half a million deaths each year, and efforts to tackle it have stalled in the face of growing populations and the disease developing a greater resistance to treatments.

This new approach offers some fresh hope for fighting malaria, and with further research, it could support other steps to stop the spread of the disease – without the risk of harm to humans or other wildlife.

"Nitisinone is a versatile compound that can also be used as an insecticide," says Acosta Serrano.

The research has been published in Science Translational Medicine.