A previously unknown species of wasp with an abdomen reminiscent of a Venus flytrap has been discovered in 99-million-year-old Kachin amber, and entomologists have never seen anything like it.

While the insect's front half would pass for that of a modern wasp, its unique rear end would raise a hymenopteran eyebrow.

"Nothing similar is known from any other insect," write the researchers behind a study on the insect's fossilized remains, led by Qiong Wu from Capital Normal University in Beijing.

"The rounded abdominal apparatus, combined with the setae along the edges, is reminiscent of a Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula), a carnivorous plant using two opposing specialized leaves to capture insect prey."

The wasp may not have eaten its own captives, but scientists think its babies probably did – from the inside, out.

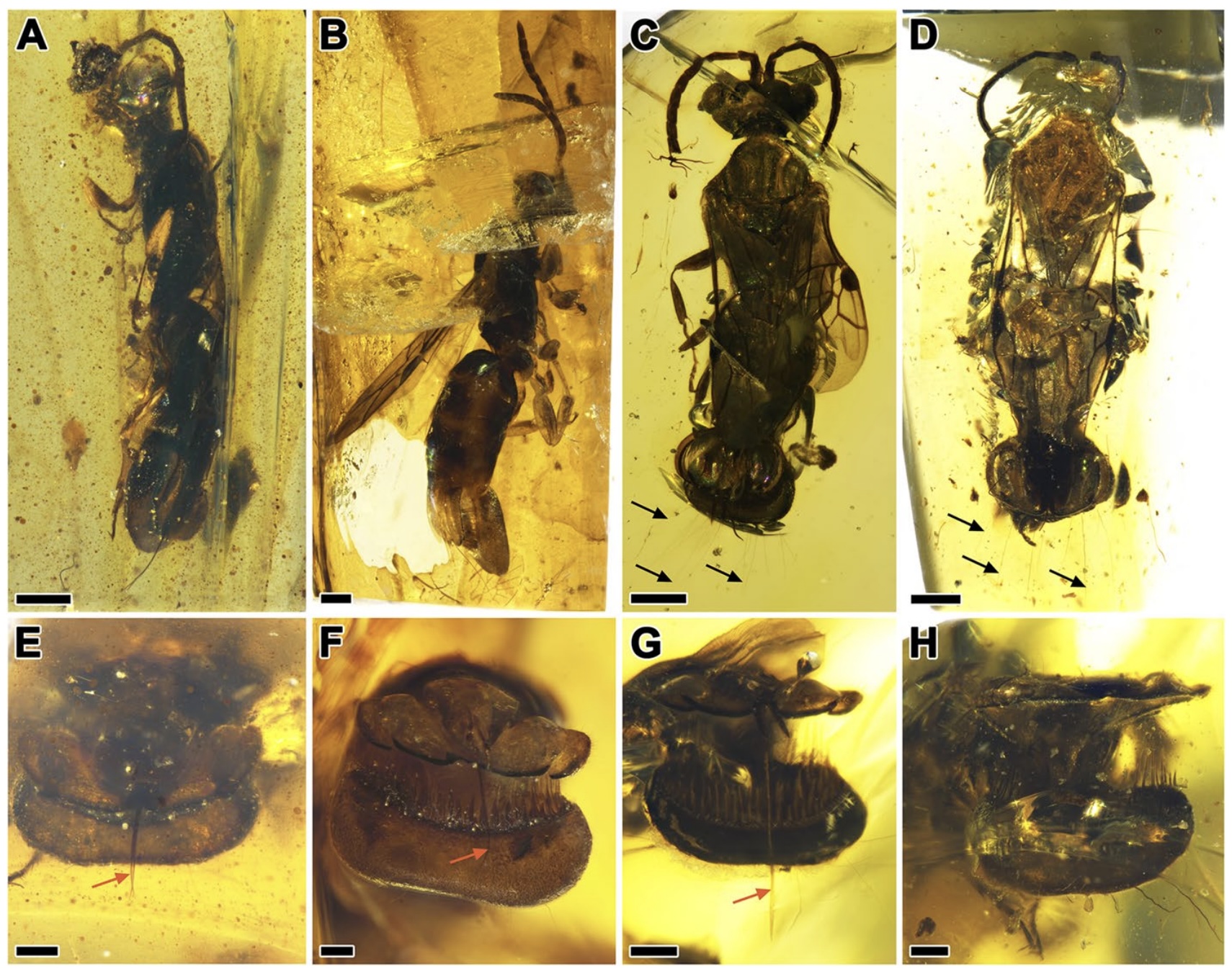

Sixteen adult female wasps were preserved in the amber well enough to describe them as a new species (and family), Sirenobethylus charybdis, all of which sport these rather unusual-looking abdomens.

Lined with hairy bristles, the lower half of this paddle-shaped structure appeared frozen into different positions across the numerous specimens like a frame-by-frame replay, hinting at its grasping, jaw-like function.

While it's possible the strange abdomen could be a means for the adult wasp to catch prey to consume, or to hold onto a mate, the researchers believe the wasp is a koinobiont parasite: the kind that lays its eggs into the bodies of live hosts to incubate until hatching.

The flaps converge around the wasp's ovipositor; the tube through which eggs are injected. The researchers think the most likely function for the strange anatomy is to therefore temporarily restrain the host during the invasive egg-laying procedure.

Many modern koinobiont wasps target slow-moving hosts like caterpillars and fly larvae to house their burgeoning offspring. This newly described wasp's grasping rear end would have broadened its options in this regard, allowing it to trap otherwise speedy hosts for long enough to inject eggs into their bodies.

Living wasps in the dryinid family similarly restrain their flighty hosts (leafhoppers, treehoppers, and planthoppers) with their forelegs, but they're also known to actively track them down beforehand, something Sirenobethylus doesn't seem built for.

But the trigger hairs on the wasp's grasper may have allowed it to instead lie in wait, its posterior maw lunging upon any hopper or fly to come within range.

"We imagine it would have waited with the apparatus open, ready to pounce as soon as a potential host activated the capture response," the authors write.

But it's difficult to verify this theory without being able to compare these female specimens with the species' males, which are missing from the record. If the trap aids only in egg-laying, then males may not have one. The absence of male specimens also makes it impossible to know whether the apparatus could have been involved in the mating process.

"Indeed, it would be unique for insect females to restrain the males during mating, rather than the other way around," the authors write. "We consider this an unlikely function of the abdominal apparatus."

This research was published in BMC Biology.