A modified pig liver transplanted into a human patient appears to have functioned normally for the duration of the investigation with no signs of rejection.

For 10 days, the liver performed its basic metabolic functions in a patient diagnosed with brain death, according to a team of doctors led by Kai-Shan Tao, Zhao-Xu Yang, Xuan Zhang, and Hong-Tao Zhang of the Fourth Military Medical University in China.

This is the first time the transplantation of a pig liver has been described in a peer-reviewed publication, offering hope for patients of late-stage liver disease for whom transplants are often the only treatment option.

"This is the world's first case of a transplant of a genetically modified pig liver into a brain-dead human," says nephrologist Rafael Matesanz of the National Transplant Organization in Spain, who was not involved in the research.

"This is an important experiment, which opens up a different path to what has been tried so far in both vital organs (heart) and non-vital organs (kidney), such as the temporary replacement of the diseased liver until a human liver can be obtained for the definitive transplant."

The availability of donor organs presents a major roadblock for patients in need of a transplant. One possible solution is xenotransplantation – taking an organ from a genetically modified animal and using it as a temporary 'bridge' until a compatible human donor becomes available.

Clinical trials on the method have so far looked promising. In 2023, a genetically modified pig liver was attached externally to a brain-dead patient's body for three days. Experiments with genetically modified pig kidneys have gone further; multiple different teams have reported normal functioning after transplantation inside brain-dead patients.

Liver functions are more complex than those of the kidney, which makes transplantation a more difficult prospect. Not all scientists have considered it even possible, especially since the fats, proteins, and glucose produced by a pig's liver could provoke a strong immune response in humans that is difficult to suppress.

In a brain-dead patient – that is, a person without brain functions considered vital for life – Tao and his team have now successfully transplanted a liver harvested from a genetically modified pig.

There were six genetic modifications, all focused on minimizing immune rejection. They included the removal of genes that mediate hyperacute rejection and the insertion of human genes to make the organ more compatible with the human body.

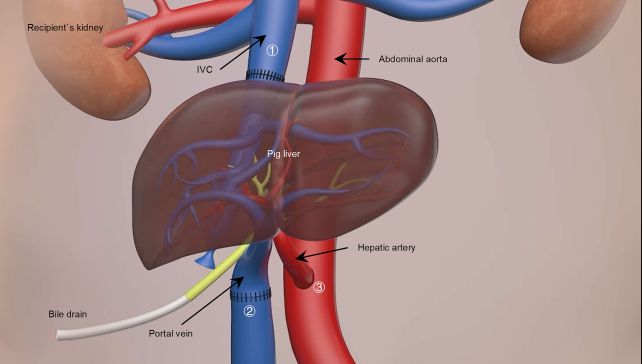

When the transplant took place, it was not a complete replacement of the patient's liver, but what is known as an auxiliary transplant. The original liver is not removed, but left intact; the pig liver is placed in another position in the abdominal cavity, connected up, and monitored.

The study was terminated after 10 days at the request of the patient's family, but the liver remained functional until the end.

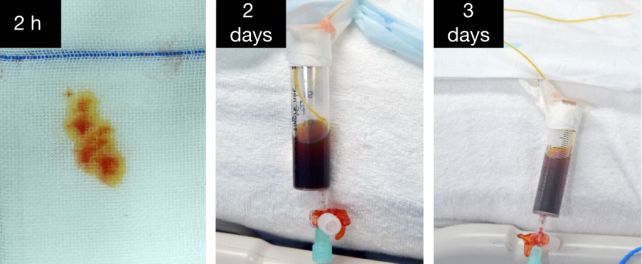

The patient's immune system didn't reject the implant thanks to the judicious application of immunosuppressants that inhibited T-cell and B-cell activity. Meanwhile, blood flow through the transplanted liver was maintained at a good velocity, and the liver itself produced both bile and porcine albumin, as a liver ought.

Because the patient still had their own functioning liver, it's difficult to ascertain whether or not the pig's liver would provide adequate function to a patient experiencing liver failure; that's a topic for future research.

What the study does show is that the genetic modifications prevent hyperacute organ rejection and the low platelet count associated with xenotransplantation. This means it's a viable option for further exploration.

"The study represents a milestone in the history of liver xenotransplantation, describing for the first time a transplantation of a genetically modified porcine liver into a human being (in this case, a brain-dead human)," says neuropathologist Iván Fernández Vega of the University of Oviedo, who was not associated with the research.

"The quality of the work is very high, both in terms of scientific rigour and the exhaustive clinical, immunological, histological and haemodynamic characterisation of the procedure."

There's a lot more to learn. Only bile and albumin production were assessed, the most basic markers of liver function. The study only included a single patient. That's understandable, but it does mean that the results can't be widely extrapolated.

Nevertheless, it's another promising step, suggesting a future potential lifeline for patients experiencing liver failure with no other treatment options while they await a human transplant.

The research has been published in Nature.