If you've ever been cold water swimming, you'll know all about the short, sharp shock it gives your senses as you plunge in. According to a new study, it can pretty quickly change the stress response of your cells too, and in a potentially positive way.

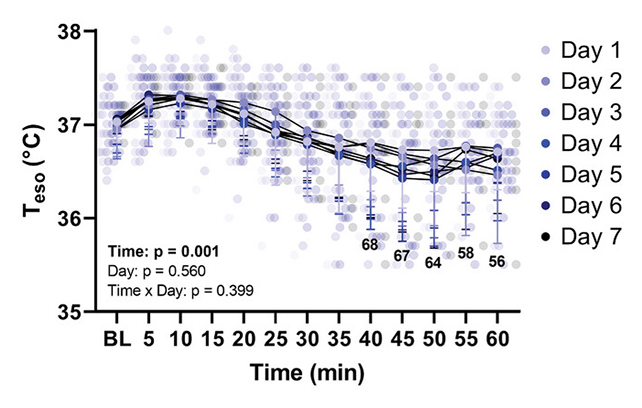

The study researchers, from the University of Ottawa in Canada, got 10 healthy young male adults to take a daily cold water dip in their lab for an hour at a time, while using blood samples to measure how their bodies were reacting on a cellular level.

After a week, the volunteers showed signs of improved autophagy, a healthy cell recycling process that clears waste. In addition, signs of apoptosis (programmed cell death) and inflammation reduced over the week, after initially spiking.

The thinking is that consistent cold water submersion may improve our body's fundamental reaction to environmental stress – in this case, chilly temperatures. Here, it made the key stress response of autophagy more protective.

"We were amazed to see how quickly the body adapted," says physiologist Glen Kenny, from the University of Ottawa.

"Cold exposure might help prevent diseases and potentially even slow down aging at a cellular level. It's like a tune-up for your body's microscopic machinery."

The researchers also note that the initial exposure to cold water – chilled to 14 °C (57.2 °F) – was more chaotic, with "dysfunction" in autophagy processes and increased apoptosis. It settled down and became more beneficial as the week went on.

This suggests the body does need time to adapt, but that the adaptation doesn't take long. The body seemed to switch from killing off cells in response to the cold conditions, to repairing cells instead.

"By the end of the acclimation, we noted a marked improvement in the participants' cellular cold tolerance," says physiologist Kelli King, from the University of Ottawa.

"This suggests that cold acclimation may help the body effectively cope with extreme environmental conditions."

There are some significant limitations to note here: first, the study only involved 10 people, who were all young men. Researchers are going to need to test this out on bigger groups of participants, including women, to see if the findings apply more generally.

The research was also carried out in a very controlled lab setting. There was none of the cold air exposure and variations in temperature that you'd get with cold water swimming for example. Previous studies have shown the way our bodies respond to cold air is different to cold water. These factors may also influence the results.

Scientists have now found both potential benefits and drawbacks to cold water exposure, but this new discovery could have long-term implications for our bodies: the recycling and cleaning that autophagy takes care of is crucial in preventing disease and limiting some of the wear-and-tear effects of aging.

"Our findings indicate that repeated cold exposure significantly improves autophagic function, a critical cellular protective mechanism," says Kenny.

"This enhancement allows cells to better manage stress and could have important implications for health and longevity."

The research has been published in Advanced Biology.