The problem of debris in Earth orbit is getting worse.

According to the European Space Agency's (ESA) annual Space Environment Report, the amount of space debris is rising quickly. We're sending satellites up at a much faster rate than they come down.

To make the problem worse, the number of satellites that are no longer functioning and chunks of broken spacecraft is vastly higher than the number of operational satellites.

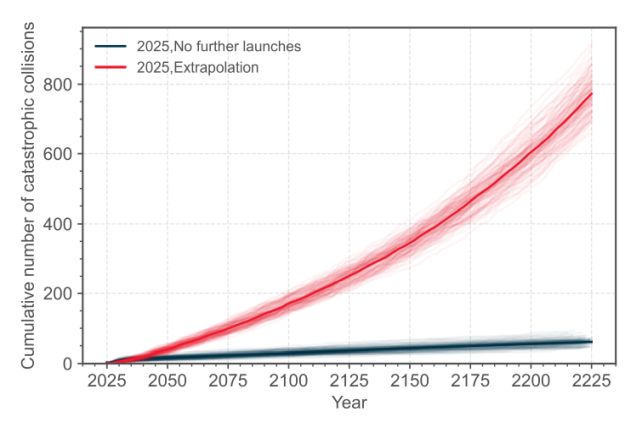

Eventually, the density of space debris will result in a runaway Kessler cascade, where collisions between objects in Earth orbit will add more material, further increasing the risk of objects smashing together to create even more debris that then flies off… you get the idea.

We're not there yet. But the risk of collisions in Earth orbit is on the rise, and will continue to surge at an alarming rate if we continue at the current rate of launches. In fact, it will continue to rise even if we launch nothing into Earth orbit ever again.

"There is a scientific consensus that even without any additional launches, the number of space debris would keep growing, because fragmentation events add new debris objects faster than debris can naturally re-enter the atmosphere, also known as the Kessler syndrome.

"This chain reaction can make certain orbits become unsafe and unusable over time as debris continues to collide and fragment again and again, creating a cascading effect," the ESA explains in a summary of the report.

"This means that not adding new debris is no longer enough: the space debris environment has to be actively cleaned up."

Scientists have known for years that the rate at which we launch satellites into Earth orbit is unsustainable. Although obsolescence is now often planned for with many satellites and rocket stages destined to burn up on atmospheric reentry once they have outlived their usefulness, it's a process that takes time.

The 2025 Space Environment Report, however, makes a sobering read even with in-built satellite destruction in mind. Currently, monitoring programs are tracking around 40,000 objects in Earth orbit, with around 11,000 being active, operational satellites.

However, the estimated amount of junk up there is far higher. According to the ESA's estimates, there are around 54,000 objects in Earth orbit larger than 10 centimeters (4 inches) across. Between 1 and 10 centimeters, there are an estimated 1.2 million pieces of space junk. And between 1 millimeter and 1 centimeter, some 130 million pieces of detritus are whipping around Earth at high speed.

That might not seem particularly scary, but tiny pieces of debris can still cause significant damage to operational satellites and spacecraft, including the International Space Station and the Hubble Space Telescope.

Fragmentation isn't limited to collisions, either. Explosive failures and regular wear and tear are examples of processes that can cause objects in orbit to shed high-velocity scrap.

In 2024, non-collisional fragmentation events were the single largest source of space debris. The ESA counted 11 such events that, between them, generated at least 2,633 pieces of space junk.

Because these events are unplanned and uncontrollable, we can't do anything to ensure that the fragments are on a decaying orbit that will see them harmlessly burn up in Earth's atmosphere.

There is some positive news, though. The number of controlled atmospheric entries of intact rocket stages and satellites was higher in 2024 than previous years, which means that this disposal strategy is working. There were also fewer uncontrolled entries.

"About 90 percent of rocket bodies in low-Earth orbits are now leaving valuable orbits in compliance with the re-entry within 25 years standards from before 2023, with more than half re-entering in a controlled manner," the ESA explains.

"About 80 percent is also compliant with the new, tightened standard of vacating orbits within five years that ESA has adopted for its own activities in 2023."

Keeping that trend going is one piece of the puzzle. Initiatives to actively clean up the space around Earth represent another. It is going to be difficult, and require global cooperation; hopefully humanity will be able to work together to keep Earth orbit a functional space for all of us.

You can read the report for yourself here.