Sets of prehistoric three-toed footprints pressed into stone have led paleontologists to discover a new dinosaur in the armored ankylosaurid family.

The trackways were found near the town of Tumbler Ridge in British Columbia, which became known for its ankylosaur fossils after Mark Turner and Daniel Helm, both young boys at the time, first discovered a trackway in 2000.

Ankylosaurids are one of the two main families of ankylosaurs, the other being nodosaurids. We know the difference between these families because of their tail armor: nodosaurids lack the bony tail club that defines the ankylosaurids.

This is the first time we've seen precious, 100-million-year-old ankylosaurid footprints, which have only three toes on their back feet, unlike their relatives' four.

Ankylosaur specialist Victoria Arbour – who also happens to be the paleontology curator at the Royal British Columbia Museum – visited Tumbler Ridge in 2023, where she met with Charles Helm, scientific advisor at the Tumbler Ridge Museum (and Daniel's father).

He showed her a number of three-toed footprint trackways that had been turning up around the area in recent years. All specimens were found within the Tumbler Ridge UNESCO Global Geopark, except for one that was found in western Alberta.

These footprints were preserved in the non-marine deposits of the Dunvegan and Kaskapau Formations, from the middle of the Cretaceous period. At this time, the now-mountainous region of the British Columbia Rockies was a lowland delta, freshly scoured with channels, point bars, shallow lakes, and mud squelchy enough to preserve the imprint of dino toes.

Trackways like this are particularly useful to paleontologists because they provide multiple footprint specimens from the same animal. And in a region lacking skeletal fossil material, well-preserved trace fossils like these are essential to understanding prehistoric life.

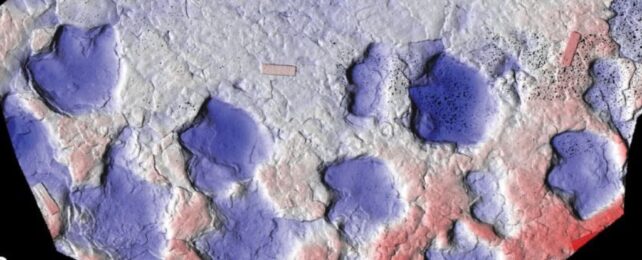

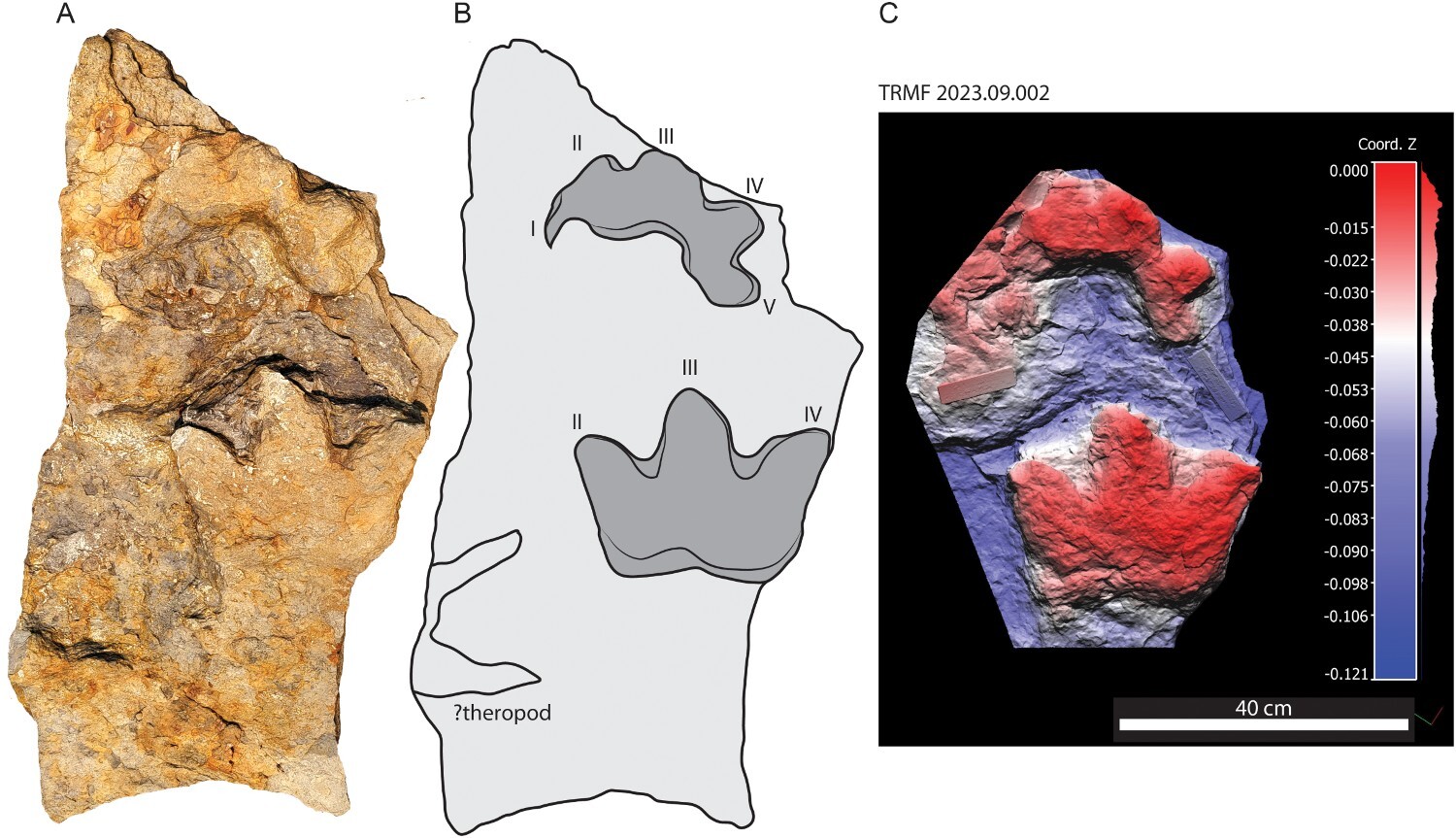

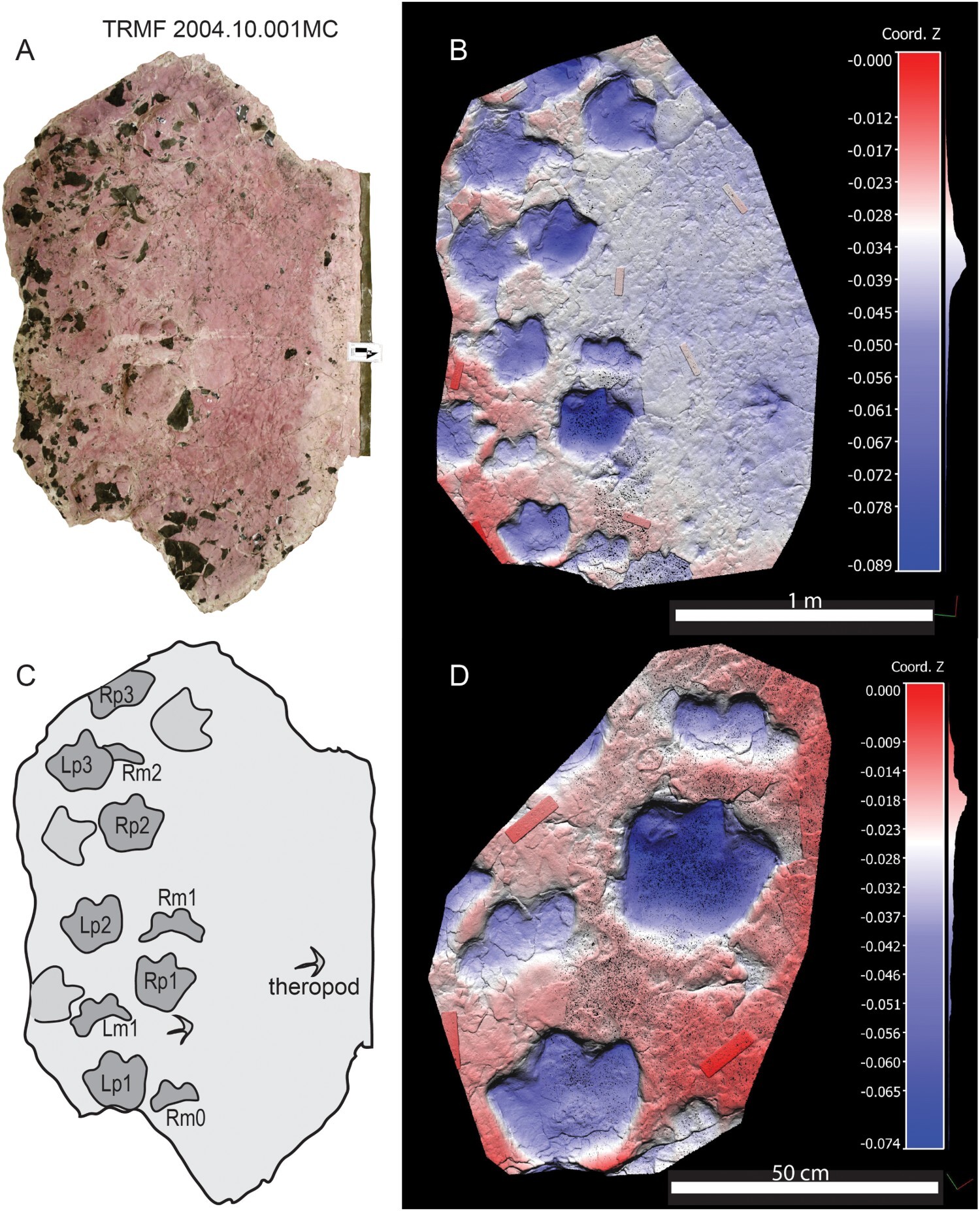

Closer analysis of the trackways, digitally rendered using photogrammetry, helped them realize they were looking at traces of a new species, which the team named Ruopodosaurus clava.

The pes (back foot) tracks have "robust digits ending in blunt triangular or U-shaped toe tips," write Arbour, Helm, and their collaborators in a paper describing the species.

The dinosaur's manus (front foot) tracks, however, bear five digits, "distinctly crescentic in form."

"While we don't know exactly what the dinosaur that made Ruopodosaurus footprints looked like, we know that it would have been about 5 to 6 meters (16 to 20 feet) long, spiky, and armored, and with a stiff tail or a full tail club," Arbour says.

"This study also highlights how important the Peace Region of northeastern British Columbia is for understanding the evolution of dinosaurs in North America – there's still lots more to be discovered."

Because no ankylosaurid bones have been found in North America from 100 to 84 million years ago, paleontologists had assumed they had disappeared from the region during the mid-Cretaceous. But the Ruopodosaurus clava trackways show the ankylosaurid family was indeed trampling around the continent at the same time as its nodosaurid cousins.

"It is really exciting to now know through this research that there are two types of ankylosaurs that called this region home, and that Ruopodosaurus has only been identified in this part of Canada," Helm says.

The findings were published in Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.