You often need a lot of patience to be a scientist, and that's certainly been the case for researchers who have now found solid evidence for a hypothesis around vitamin B1 (or thiamine) that was first put forward almost 70 years ago.

In 1958, Columbia University chemist Ronald Breslow proposed that vitamin B1 performs key metabolic processes in the body by forming a molecular structure known as a carbene.

The problem: carbenes are highly unstable and reactive, and usually break down instantly in water. They should, by all accounts, be incompatible with the body's high water content.

But researchers led by a team from the University of California, Riverside (UC Riverside) have now managed to keep a carbene intact in water for months in their lab.

"This is the first time anyone has been able to observe a stable carbene in water," says chemist Vincent Lavallo, from UC Riverside. "People thought this was a crazy idea. But it turns out, Breslow was right."

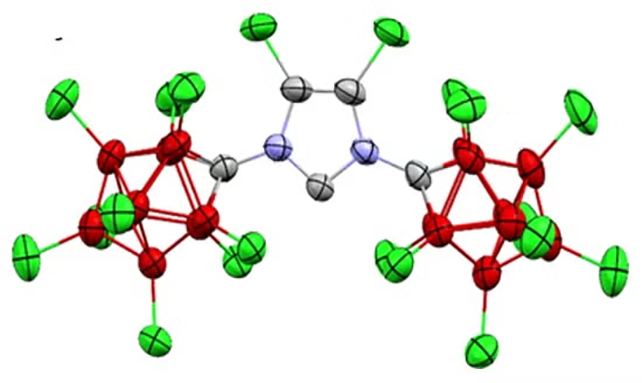

Key to the breakthrough was the way the researchers were able to synthesize a "suit of armor" molecule in the lab, to wrap around the carbene and keep it intact. The team was able to use high-resolution imagery to verify the composition of the carbene.

Through some other chemical tweaks on top of the protective structure, the carbene could be kept stable in water for as long as six months. It shows that carbenes can be biologically feasible, and that vitamin B1 may take on that form to do its work in the body.

What's more, the researchers think that the approach they've used here could have industrial applications. Being able to stabilize carbenes could allow water to replace more toxic and dangerous substances in chemical reactions in the future, making for a cleaner way to produce things like pharmaceuticals and fuels.

"Water is the ideal solvent – it's abundant, non-toxic, and environmentally friendly," says chemist Varun Raviprolu, from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). "If we can get these powerful catalysts to work in water, that's a big step toward greener chemistry."

There's a twist here: the researchers were investigating the chemistry of reactive molecules in general, not looking to prove Breslow's hypothesis. It's another example of the serendipitous scientific discoveries that can sometimes come from careful research.

The research also acts as a reminder not to give up on a promising idea, even after almost six decades. There's plenty more to explore here for scientists – not least why the extra protection of the molecule seemed to reduce its reactivity – but Ronald Breslow would be happy to see his prediction was right.

"There are other reactive intermediates we've never been able to isolate, just like this one," says Lavallo. "Using protective strategies like ours, we may finally be able to see them, and learn from them."

"Just 30 years ago, people thought these molecules couldn't even be made. Now we can bottle them in water. What Breslow said all those years ago – he was right."

The research has been published in Science Advances.