Love is one of the biggest human mysteries - people write songs about it, die for it and dedicate their lives to it. But what, exactly, is it? Scientists believe that they may finally have found the answer, after discovering the first evidence of changes in the love-struck brain.

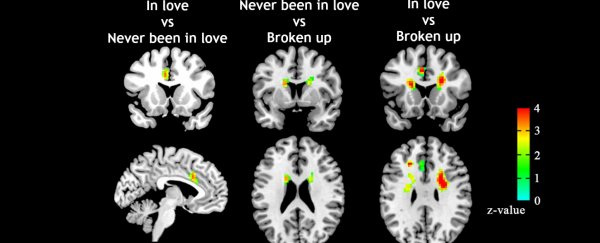

The team scanned the brains of 100 students recruited from Southwest University in China and found clear changes in the areas of the brain involved in reward, motivation, emotion and social interactions when someone was in love. Their results have been published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, and you can see the full figure above here.

"The results shed light on the underlying neural mechanisms of romantic love, and demonstrate the possibility of applying a resting-state fMRI approach for investigating romantic love," the authors wrote in the paper.

The researchers used resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to compare the brain activity of three different groups - 34 people who had been in love for between four and 18 months, 34 who had recently broken up with someone they loved, and 32 who had never been in love at all. Across the three groups there was no significant difference in age, personal monthly expenses, family income, or years of education.

During the scans, the participants were told to think of nothing in particular, so the scientists could get an understanding of how their brains worked overall.

They found that those who were "in love" had increased activity in several areas of their brains, including the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, insula, caudate, amygdala, and nucleus accumbens, as well as the temporo-parietal junction, posterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, inferior parietal, precuneus, and temporal lobe.

In many of these brain regions, the amount of activity they saw was linked to the amount of time someone had been in love. So, the longer they'd loved someone, the more activity they experienced.

On the other hand, the longer the "ended love" group had been broken up, the lower activity in these regions. They also showed that one area of the brain, the caudate nucleus, seemed to be involved in helping people cope with the end of a love affair.

Of course, knowing this isn't really going to help you work out whether or not your boyfriend or girlfriend really loves you, or even whether your love is the kind of love that's going to last. But the researchers believe it could lead to a better understanding of the emotion, and could give scientists the ability to 'diagnose' whether someone really is in love or not.

However, before we get too carried away, there are a few flaws the study, the biggest being that its findings are all based on students self-classifying whether or not they were in love in the first place. And there's also not a clear base level of brain activity established. An interesting follow-up would be to compare people's brain activity between when they're in love to when they aren't to eliminate individual neural differences.

The researchers acknowledge this, and explain that longitudinal studies are now needed to verify their findings. And they also put forward another (slightly depressing) limitation of their study: "We do not know exactly whether love-related alterations are adaptation, or maladaptation in lovers." Which basically means they're not sure whether the brain-changing experience of falling head over heels in love is doing us more harm than good, and they suggest future studies determine this.

So there's still a lot to learn about love, but as far as taking steps towards understanding the biological basis of human emotions go, this is a pretty big one. We can't wait to find out more.