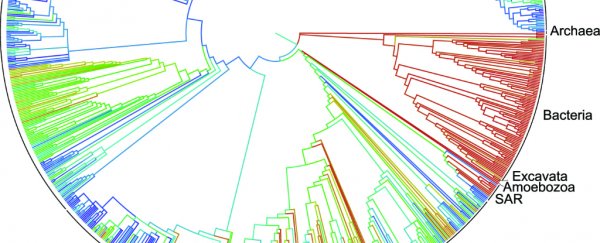

The first draft of the most comprehensive 'tree of life' has been released, revealing the relationships shared by all the named species of plants, animals, fungi, and microbes on Earth - roughly 2.3 million of them.

Tracing the evolution of life from its beginnings more than 3.5 billion years ago to today, the tree of life was constructed by scientists from 11 research institutions around the world, and fills in the gaps left by the thousands of smaller trees that have come before it. "This is the first real attempt to connect the dots and put it all together," principal investigator Karen Cranston from Duke University in the US said in a press release. "Think of it as Version 1.0."

The first draft is based on 500 smaller trees, and a survey of more than 7,500 phylogenetic studies published between 2000 and 2012 in more than 100 academic journals.

Everything - including the underlying data and source code - has been made available to browse and download at the Open Tree of Life website, which will help other researchers refine the existing information and add to the current draft. The team is now developing software that will allow them to log in and edit the tree as new data becomes available on newly described species.

"There's a pretty big gap between the sum of what scientists know about how living things are related, and what's actually available digitally," Cranston said.

One of the biggest challenges the researchers faced - apart from dealing with phylogenies that were not digitised - was resolving the name changes, alternate names, common misspellings and abbreviations that have been cropping up since we started classifying species more than 250 years ago. "For instance," Maddie Stone writes for Gizmodo, "in a strange fluke of taxonomy that I can only hope has inspired some fantastically weird artwork, spiny anteaters once shared their scientific name with moray eels."

The draft version has been published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The value of a comprehensive tree of life isn't just in showing how all named species on Earth relate to one another - it can bring a greater understanding of how some of the deadliest diseases known to science, such as HIV, ebola, and influenza, first appeared and then spread, and can reveal better techniques for crop and livestock yields, for example.

"With bigger and more resolved trees we can answer evolutionary questions on scales not previously possible," the team blog reads. "Sparse lineage sampling and hence unaccounted for diversity has previously been a hindrance when analysing evolutionary trends that span the tree of life, but the time is approaching (or might be here already!) where the size of the phylogenies will not be the limiting factor in studying broad scale evolutionary questions."

View the Open Tree of Life here.