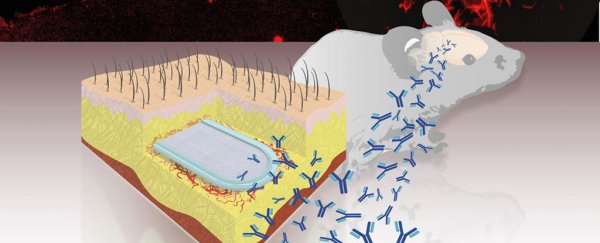

Scientists in Switzerland have developed an ambitious new treatment to fight Alzheimer's disease, with a capsule device that's planted under the skin to provide an ongoing defence against the sticky proteins that are hypothesised to cause the illness.

Those proteins are called amyloid beta, and the capsule implant contains cells that have been genetically engineered to counteract them. The cells do so by producing antibodies that provoke the recipient's immune system to fight their build-up before they can form into harmful plaques that impede synaptic connectivity, memory recall, and general cognition.

The technique, developed by researchers at École Polytechnique Dédérale de Lausanne, has only been tested in mice so far, but early results are promising. In animal models of Alzheimer's disease, the implant caused a dramatic reduction of aggregated protein plaques, which are toxic to neurons.

One of the benefits of the capsule is that it stays in position under the skin, producing a constant flow of antibodies to fight amyloid beta. Publishing in the journal Brain, the team says this ongoing defence against Alzheimer's prevented plaque formation over the course of 39 weeks, and it also disrupted the functioning of tau, another protein hypothesised to be a cause of the disease.

The technique of 'tagging' amyloid beta proteins with antibodies is not itself new, but existing treatments require repeated vaccine injections, which can cause side effects, and the procedure needs to commence before the patient shows signs of cognitive decline.

École Polytechnique Dédérale de Lausanne

École Polytechnique Dédérale de Lausanne

The implant gets around this by essentially staying silently on guard, only responding to fight the sticky proteins if and when they show up in the brain.

The capsule, called a "macroencapsulation device" is made of two permeable membranes that are sealed together with a polypropylene frame. The implant measures 27 mm long by 12 mm wide and is 1.2 mm thick, and contains a hydrogel that facilitates the growth of cells contained within.

The membranes shield the cells inside the capsule from the patient's immune system, but their permeability lets them derive any nutrients they need to survive from surrounding tissue.

According to the researchers, all the materials used to create the implant are biocompatible, and the system of making the capsules could be easily reproducible in large-scale manufacturing.

Of course, if this technique were to be used in humans one day, it's likely the design and dimensions of the capsule would be revised. Before that happens, there'd need to be an awful lot more research done to make sure the device was safe – but we have to say it looks pretty amazing as a proof-of-concept so far. Watch this space.