New research has shown in the most detail yet how rapidly Earth's magnetic field - which acts like a shield to protect us from harsh solar winds and cosmic radiation - is changing, getting weaker over some parts of the world, and strengthening over others.

Although invisible, these changes can have big impacts - the fluctuation is already shifting the location of the magnetic North Pole, and could determine how space events such as solar storms affect us in the future. But thanks to the new study, scientists now think they know what's causing them, and how to predict them going forward.

This isn't the first research to show that Earth's magnetic field is changing. Our magnetic field has always been in flux, and over the past few years it's become clear that the invisible bubble that protects our planet from the harsh conditions of outer space has been getting weaker and weaker.

According to scientists' best estimates, the field is now weakening around 10 times faster than initially thought, losing approximately 5 percent of its strength every decade. But they don't really know why, or what that means for our planet.

One of the most likely explanations for what we're seeing is that our magnetic poles are getting ready to flip - something that happens once every 100,000 years or so, and that sounds a lot scarier than it really is. There's no evidence that life on Earth suffered when this happened in the past - the most likely impact is that our compasses would eventually point south instead of north.

"Such a flip is not instantaneous, but would take many hundred if not a few thousand years," Rune Floberghagen from the European Space Agency (ESA) told LiveScience back in 2014. "They have happened many times in the past."

But despite the overall message being 'don't panic', scientists still know relatively little about our magnetic field, so in 2013, ESA launched a trio of satellites called Swarm, which measure Earth's magnetic field from signals coming from Earth's core, mantle, crust, oceans, ionosphere, and magnetosphere.

Using that data and those from other satellites, they've just released the clearest map so far of exactly how our magnetic field is changing - where it's weakening and strengthening - and what's causing those shifts. Importantly, it reveals just how fast these changes are taking place.

Presenting at the annual Living Planet Symposium in Prague last week, ESA researchers showed that the magnetic field has weakened by about 3.5 percent over the top of North America since 1999, but has strengthened by roughly 2 percent over Asia in that same time period.

The weakest part of the magnetic field, the South Atlantic Anomaly, which is over South America, moved steadily westward over the past seven years, and also weakened by 2 percent (and, yes, overall the whole thing is still weakening). On top of all that, the North Pole is wandering eastward towards the Asian continent pretty quickly.

You can see those changes in the animation below. Red shows a strong magnetic field, and blue shows a weak one:

You can also see where the changes have sped up (red) and slowed down (blue) between 2000 and 2015:

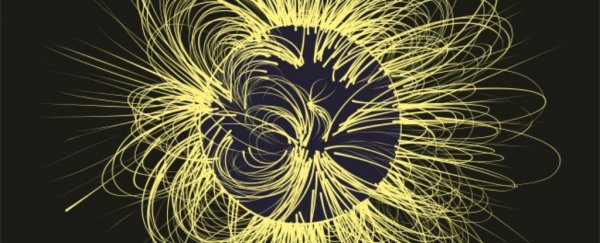

So why are these changes happening? Our magnetic field is widely thought to be produced by an ocean of molten, swirling iron that makes up our planet's outer core, 3,000 km below our feet. That spinning liquid acts like a bicycle dynamo, generating electrical currents that control the electromagnetic field around the planet.

But although that dynamo core was long hypothesised to be responsible for changes in the magnetic field, this is the first time the researchers have been able to map changes in both the liquid iron inside our planet and the field surrounding it simultaneously - and the results show that the two are closely linked.

"Swarm data are now enabling us to map detailed changes in Earth's magnetic field, not just at Earth's surface but also down at the edge of its source region in the core," said Chris Finlay from DTU Space in Denmark, who led the ESA project.

"Unexpectedly, we are finding rapid localised field changes that seem to be a result of accelerations of liquid metal flowing within the core."

The research hasn't been peer reviewed as yet, so for now we're taking the ESA's word for it, but if confirmed, this means we finally have some solid evidence as to what's controlling the shifts we're seeing - and that could help us predict what's going to happen next. For example, how worried we need to be about the next big solar storm.

The research could also help us finally understand why our planet's magnetic field is weakening overall, and how that's going to affect us in future. Because a pole flip probably won't be a big deal, but it's nice to make sure - if our magnetic sphere is about to go the way of Mars's, that's something we need to know about.