For the first time, scientists have shown that even if a patient's own immune cells are incapable of recognising and attacking tumours, someone else's immune cells might be able to.

In a new study, scientists have shown that by inserting certain components of healthy donor immune cells (or T cells) into the malfunctioning immune cells of a cancer patient, they can 'teach' these cells how to recognise cancer cells and attack them.

"In a way, our findings show that the immune response in cancer patients can be strengthened; there is more on the cancer cells that makes them foreign that we can exploit," says one of the team, Ton Schumacher from the Netherlands Cancer Institute.

"One way we consider doing this is finding the right donor T cells to match these neo-antigens," he says. "The receptor that is used by these donor T-cells can then be used to genetically modify the patient's own T cells so these will be able to detect the cancer cells."

It's now abundantly clear that existing treatments that try to kill off cancer cells by pumping the body full of harmful chemicals (aka chemotherapy) or incredibly hot bursts of laser light (radiation therapy) are woefully inadequate, so scientists around the world have been looking to something called immunotherapy as the next big hope.

Rather than using lasers or chemicals to attack cancer cells (and also healthy cells nearby), immunotherapy is based on the idea that certain treatments could bolster a patient's own immune system to fight the cancer on its own.

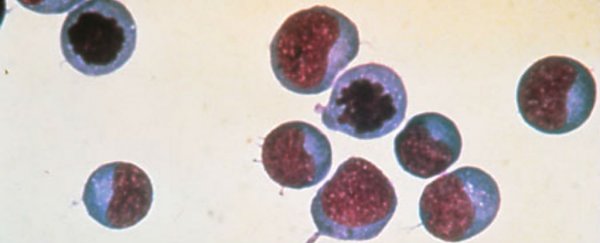

Ideally, when a patient gets sick, their own T cells - or white blood cells - are responsible for detecting foreign or abnormal cells, and once they've locked onto their target, they bind with them and signal to the the rest of the immune system that they need to be attacked.

But when it comes to cancer, T cells can fail for two main reasons: either certain 'barriers' are in place that interfere with their ability to target and bind cancer cells, or they simply don't recognise the cancer cells as something they need to take note of and destroy in the first place.

Scientists have recently seen some really promising results in a trial where defective T cells were extracted from the blood of leukaemia patients, reprogrammed to target the specific type of cancer, and inserted back into the body to more effectively fight the disease.

"In one trial, 94 percent of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia saw their symptoms disappear entirely," Fiona MacDonald reported for us back in February. "For patients with other types of blood cancer, response rates have been above 80 percent, and more than half have experienced complete remission."

Another way to address a malfunctioning immune system is by using a healthy immune system to kick it back into gear. In this most recent study, a team from the Netherlands Cancer Institute and the University of Oslo extracted T cells from healthy donors, and inserted mutated DNA from a patient's cancer cells into them.

They identified the correct DNA sequences by mapping certain protein fragments called neo-antigens on the surface of cancer cells from three patients at the Oslo University Hospital.

In all three patients, the cancer cells seemed to display a large number of different neo-antigens, but none were picked up by their own T-cells. Fortunately, they did stimulate an immune response in the healthy donor immune cells.

The team inserted active components from these donor immune cells into the immune cells of the three cancer patients, and found that this prompted their own immune cells to effectively recognise the neo-antigens on the surface of the cancer cells, and kickstart an immune response.

So basically, they're using a 'borrowed' immune system to help the existing immune system 'see' the cancer cells for the first time.

While this is just a proof-of-concept study with only three participants, the results are promising enough that the treatment will hopefully be tested in a much wider clinical study in the future.

What we're beginning to see more and more is the idea that cancer treatments need to be more personalised, and quite simply smarter than what's been offered for several decades now, and addressing the things that are holding back an individual's own immune system from doing its job just might be the answer.

If you're not convinced, this billionaire just invested US$250 million into getting immunotherapy to the forefront of cancer research.

"Our study shows that the principle of outsourcing cancer immunity to a donor is sound. However, more work needs to be done before patients can benefit from this discovery," said one of the team, Johanna Olweus.

"We are currently exploring high-throughput methods to identify the neo-antigens that the T cells can 'see' on the cancer and isolate the responding cells. But the results showing that we can obtain cancer-specific immunity from the blood of healthy individuals are already very promising."

The results have been published in Science.