Astronomers working with NASA's Dawn spacecraft have found evidence that the mysterious bright spot inside the Occator Crater on Ceres – a dwarf planet located inside our galaxy's asteroid belt – is a massive amount of sodium carbonate: a type of salt.

The findings also suggest that the core of Ceres is hotter than previously thought, and the carbonate might be left over from an ancient body of water.

But before we jump into the new study, let's have a quick refresher on Ceres and the Occator Crater in general. For starters, Ceres is a small, dwarf planet that has a diameter of roughly 945 kilometres (587 miles), accounting for 25 percent of all the mass in the asteroid belt – a region of space between Mars and Jupiter.

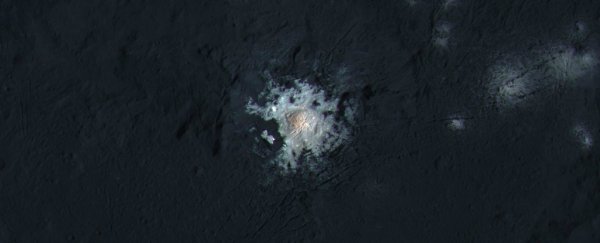

The mystery surrounding the bright spots found in the Occator Crater – an impact crater on the surface of Ceres that's about 80-million-years-old and 92 kilometres (57 miles) wide – started back in early 2015 when researchers working with the Dawn space probe discovered them.

Since then, scientists have been trying to figure out what type of material these spots are made of, especially since they stand out like a diamond in the rough, compared to their rather dull surroundings.

Now, NASA researchers might have finally cracked the case, because they've found evidence suggesting that the bright material is actually sodium carbonate – a type of salt typically found around hydrothermal environments here on Earth.

This suggests that the material could have originated inside Ceres and was brought to the surface after Occator Crater formed 80 million years ago.

"This material appears to have come from inside Ceres because an impacting asteroid could not have delivered it," the team reports.

"The upwelling of this material suggests that temperatures inside Ceres are warmer than previously believed. Impact of an asteroid on Ceres may have helped bring this material up from below, but researchers think an internal process played a role as well."

While the findings might solve the overarching mystery of the bright spots, they also suggest that Ceres might have once been home to some sort of underground ocean that stayed in liquid form until coming to the surface and freezing.

NASA

NASA

"The minerals we have found at the Occator central bright area require alteration by water," said the team's lead investigator, Maria Cristina De Sanctis, from the National Institute of Astrophysics in Rome. "Carbonates support the idea that Ceres had interior hydrothermal activity, which pushed these materials to the surface within Occator."

The team figured this out by using NASA's Dawn spacecraft – which set out to study Ceres back in 2007 – to examine the wavelengths of the reflected light coming off of the bright spots. With these precise measurements, they were able to ascertain what material was causing the reflection.

"It's amazing how much we have been able to learn about Ceres' interior from Dawn's observations of chemical and geophysical properties. We expect more such discoveries as we mine this treasure trove of data," said the Dawn mission's principal investigator, Carol Raymond, from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

This isn't the first time that researchers have hypothesised what the bright spots are made of. Last year, a separate team of researchers pointed to a type of magnesium sulphate called hexahydrite – a material that is sort of like Epsom salt – as the cause of the spots. Who doesn't love a good space mystery?

The new study was has been published in Nature.