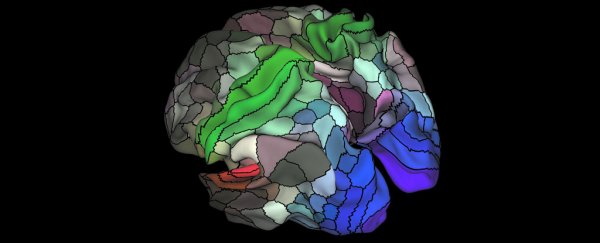

Scientists have created the most detailed map of the human brain ever, using brain scans of hundreds of people to identify almost 100 new regions in the cerebral cortex.

While researchers have been charting the brain for over 150 years, the new map – which delineates 180 cortical areas – will give scientists unprecedented understanding of how we think, talk, and feel – and offer new insights into disorders like autism, schizophrenia, and dementia.

"The brain is not like a computer that can support any operating system and run any software," said neuroscientist David Van Essen from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, who led an international team of researchers for the study.

"Instead, the software – how the brain works – is intimately correlated with the brain's structure – its hardware, so to speak. If you want to find out what the brain can do, you have to understand how it is organised and wired."

To draw their map, the scientists drew upon data from the Human Connectome Project, a long-term study scanning the brains of 1,200 young adults with a custom-built MRI machine.

From this sample, the researchers looked at the scan data of 210 healthy young men and women. The scans recorded measurements of the particpants' cerebral cortex – the outer layer of folded, neural tissue that encases the brain and primarily controls our memory, thought, language, consciousness, and senses.

The volunteers had their brains scanned both at rest and while performing simple mental tasks – like listening to a story, or doing memory tests – to measure brain activity and see how different regions of the brain were responding.

With the scans in hand, they then used a machine learning algorithm designed specifically by researchers from Oxford University in the UK to identify discrete regions of the brain, finding common cortical coordinates between all the different scans.

And then – just to be safe – they ran all this against the scans of a different set of 210 healthy young adults, to confirm what they were seeing.

The end result? Some 180 new regions in each brain hemisphere mapped by the team, confirming 83 that had been identified in previous research, and adding 97 new areas that hadn't been noticed before – or which haven't become established in scientific literature.

It's not easy to map these brain regions, as they're not clearly marked in physiology like Earth's geographical boundaries. Rather, they're vague and complicated, akin to something more like political subdivisions, Essen explained to Victoria Turk at Motherboard.

"[T]here's not a sharp dividing line where suddenly red turns to green or blue. Rather, there are gradual transitions, indicating that there's intermixing and coordination among different sensory modalities and cognitive domains," he said.

"They are based not on the folds of the cortex per se, but rather on the intricate interactions, communications, and connections between the many billions of neurons that make up the cerebral cortex."

As such, some of the regions are more clearly understood than others. One called 55b lights up when we hear a story, and is clearly linked to language. But many others are new to researchers, and some appear to be linked to more than one kind of mental function, meaning it could be some time before scientists fully understand the relevance of the new brain cartography and its divisions.

"Another interesting area is POS2," one of the researchers, Matthew Glasser, told George Dvorsky at Gizmodo. "This is an area that had not previously been mapped before neuroanatomically. We don't yet know what it is doing, but given its unique pattern, it will likely be something very specialised."

The researchers were inspired to make the new map after the frustration of having to deal with very old brain charts that have taken root in science as research staples. For example, an ancient brain map drawn up German neuroanatomist Korbinian Brodmann is still regularly used for reference purposes, despite being more than a century old.

"My early work on language connectivity involved taking that 100-year-old map and trying to guess where Brodmann's areas were in relation to the pathways underneath them," Glasser said in a press release. "It quickly became obvious to me that we needed a better way to map the areas in the living brains that we were studying."

In the same way, the researchers are under no illusions about their own mapping of the brain's complex territory, as they're well aware their efforts will be improved upon by the neuroscientists of tomorrow.

"We ended up with 180 areas in each hemisphere, but we don't expect that to be the final number," said Glasser. "In some cases, we identified a patch of cortex that probably could be subdivided, but we couldn't confidently draw borders with our current data and techniques. In the future, researchers with better methods will subdivide that area. We focused on borders we are confident will stand the test of time."

Indeed, those refinements are something the team is eager for other scientists to contribute, because as advanced as their new study is, they know there's still so much more we can discover about the brain – likening their current map to a 19th century map of the world. Lots of information, but still unarguably primitive and limited.

"Our aspiration is to make the best possible maps that we can, but we have to be honest in saying our understanding, even with this new paper that's come out, is not the equivalent of a Google map," Essen told Motherboard. "We don't have the ability to navigate the cerebral cortex down to the level of individual neurons or even tiny patches."

You can find out more about the brain map in the video below.

The findings are reported in Nature.