A new drug trial for Alzheimer's patients has just been completed, and researchers are calling the results the most promising yet in the fight against the disease.

The drug targets amyloid deposits - toxic proteins linked to the onset of Alzheimer's - and after just 12 months, patients on the highest dose had no detectable signs of these deposits.

Not only that, but for the 20 early-stage Alzheimer's patients who took the highest dose of the drug for more than six months, there were indications that their cognitive decline and memory loss had been slowed down.

"This is the best news we've had in my 25 years of doing Alzheimer's research, and it brings hope to patients and families affected by the disease," one of the researchers, neurologist Stephen Salloway from Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, told Nature.

"Compared to other studies published in the past, the effect size of this drug is unprecedented," another of the team, Roger Nitsch from Zurich University, Switzerland, told The Independent.

Before we go into the details, let's be clear that this is just one trial with a small number of participants, and "cautiously optimistic" is the name of the game here.

Nothing is confirmed until the results are replicated in a much longer trial with a larger and more diverse sample set, so while we can be excited about the incredible potential of this drug, we need to wait for follow-up trials.

So with that in mind, here's what happened.

The team recruited 165 participants who had been diagnosed with the early stages of Alzheimer's disease to test the efficacy of a drug based on an antibody called aducanumab.

Aducanumab has been shown to naturally occur in people who age without experiencing significant cognitive decline, so the researchers decided to see what would happen if they injected high doses of the antibody into people with early-stage Alzheimer's.

It's not clear how this antibody works, but the team announced at a recent conference that it appears to target amyloid deposits in the brain, but not in the bloodstream.

"The hypothesis suggests antibodies that attack amyloid in the bloodstream get sidetracked and never make it into the brain," Karen Weintraub explains over at Scientific American. "By focusing on brain amyloid, aducanumab seems to be able to cross into the brain to reach its target."

The 165 participants were split into different groups, and some received the aducanumab drug in different doses, and one group of 40 received a placebo.

Of the 103 patients who were given the drug once a month for up to 54 weeks, they all experienced a reduction in the amount of amyloid deposits in their brains. And the researchers found that the higher the dose, the more deposits were cleared from the brain.

In the group of 21 patients who received the highest dose, no detectable signs of amyloid deposits remained in their brains after a year.

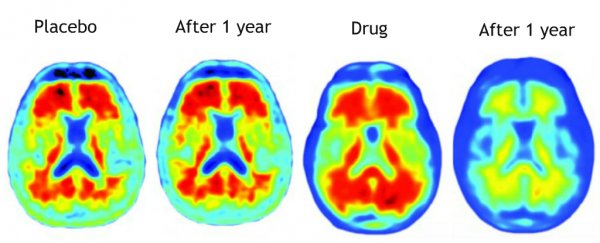

The red represents amyloid-beta plaques. Credit: Ayres, Michael/Sevigny et al/Nature

The red represents amyloid-beta plaques. Credit: Ayres, Michael/Sevigny et al/Nature

Similar results were reported in a pre-trial mouse study, which saw mouse brains cleared of amyloid deposits after aducanumab treatment.

"This drug had a more profound effect in reversing amyloid-plaque burden than we have seen to date," Alzheimer's researcher Eric Reiman from the Banner Alzheimer's Institute in Phoenix, Arizona, who is not involved in the study, told Erika Check Hayden at Nature.

"That is a very striking and encouraging finding and a major advance."

No one's entirely sure what causes Alzheimer's disease, but it's thought to result from a buildup of two types of lesions in the brain: amyloid deposits - or 'plaques' - and neurofibrillary tangles.

Amyloid deposits sit between the neurons as dense clusters of beta-amyloid molecules - a sticky type of protein that easily clumps together - and neurofibrillary tangles are caused by defective tau proteins that clump up into a thick, insoluble mass inside the neurons.

This causes disruptions to the transportation of essential nutrients around the brain, which is thought to bring on the cognitive decline and memory loss associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Over the years, the roles of amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary tangles in the onset of Alzheimer's have been debated, because it's not yet clear if one causes the other, or if one has a greater overall effect.

But this new trial suggests that if you can get rid of the amyloid deposits, you have a chance at stalling the progression of the disease. The researchers report that they saw slower cognitive declines in 91 patients treated with the drug.

"Aducanumab also showed positive effects on clinical symptoms," Nitsch explained in a press statement. "While patients in the placebo group exhibited significant cognitive decline, cognitive ability remained distinctly more stable in patients receiving the antibody."

The results are definitely exciting, but it's time to replicate them in a larger group of patients. The team is now recruiting another 2,700 patients from 20 different countries to participate in a new 18-month trial, the results of which are expected in 2020.

"These results are the most detailed and promising that we've seen for a drug that aims to modify the underlying causes of Alzheimer's disease," James Pickett, head of research at the Alzheimer's Society, who was not involved in the study, told Ian Johnston at The Independent.

"No existing treatments for Alzheimer's directly interfere with the disease process – and so a drug that actually slows the progress of the disease by clearing amyloid would be a significant step."

The results have been reported in Nature.