Scientists have revisited data from NASA's 1976 mission to Mars, and say the recent evidence of water, organic molecules, and methane in the Martian environment means we have to consider that life was discovered on the Red Planet four decades ago.

The researchers, who found ambiguous chemical signals in Martian soil collected by NASA's two Viking landers in 1976, say that everything we've discovered on Mars since makes the case for biological activity stronger than ever.

"Even if one is not convinced that the Viking results give strong evidence for life on Mars, this paper clearly shows that the possibility must be considered. We cannot rule out the biological explanation," says NASA astrobiologist Chris McKay, senior editor of the journal Astrobiology, where the paper has been published.

To be clear, the two researchers - Gilbert V. Levin from Arizona State University and Patricia Ann Straat from the US National Institutes of Health - aren't claiming that the 1976 Viking mission definitely found life.

But what they are saying is when they examined the biological and non-biological hypotheses to explain what the landers originally found, the experimental evidence pointed to extant life being a "strong possibility", whereas the non-biological interpretations were "not conclusive".

This goes against the widespread opinion at the time (and ever since) that the results of the Viking labeled release (LR) experiment, which involved on-site soil analysis by the landers, did not produce signs of biological processes.

"[I]n the absence of a non-biological agent that satisfies all Viking findings, and in view of environmental evidence that Mars may well be able to support extant life, it seems prudent that the scientific community maintain biology as a viable explanation of the LR experimental results," they conclude.

Okay so let's take a step back here and run through the history of this very weird case.

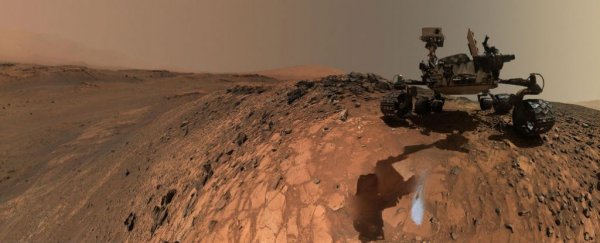

NASA's Viking Mission to Mars involved sending two spacecraft, Viking 1 and Viking 2, to Mars to obtain high resolution images of the Martian surface, characterise the structure and composition of the atmosphere and surface, and to search for evidence of life.

Viking 1 arrived at Mars on 19 June 1976, and Viking 2 touched down at the Utopia Planitia on 3 September 1976.

During their time on the surface, the landers performed the LR experiment, where samples of Martian soil - collected 6,437 km (4,000 miles) apart - were mixed with a drop of dilute aqueous nutrient solution.

The gas produced by this reaction was then monitored for hints of biological processes at work in the soil. Specifically, if the radioactive 14CO2 isotope was detected, it could be considered as evidence of microorganisms in the soil metabolising certain nutrients.

To everyone's surprise, the samples tested positive for this isotope.

"The minute the nutrients were mixed with the soil sample, you got something like 10,000 counts [of radioactive molecules]," Joseph Miller, a former NASA space shuttle project director who was involved in the original experiment, told National Geographic.

That was a huge spike from the 50 or 60 counts that usually result from the natural background radiation on Mars.

A number of control experiments were also performed, including heating some Martian soil samples to different temperatures, and keeping others in the dark for months - things that were supposed to 'kill off' any life in the soil. These samples came back negative for the isotope, which only strengthened the case for life.

But when the landers performed follow-up experiments, they all delivered negative results, and NASA dismissed the possibility of microbe detection outright.

Just about everyone argued that the original signals were geological rather than biological, but Levin and Straat have been arguing the case for life ever since.

Now they've come out with a new paper that claims everything we've found on Mars since 1976 puts geological explanations into even greater question.

"The general consensus at the time of Viking was that the LR positive response was non-biologically caused," they explain. "However, since then, information from later missions to Mars has called the basis of that consensus into question, and it is timely to reconsider a biological explanation for the LR results."

"[S]o far, no non-biological explanation has met all the criteria," they add.

Their argument focusses on the fact that in recent years, we have evidence to suggest that Mars isn't as inhospitable as we once thought. They say signs that water played a big role in much of Mars's history could mean life arose in more when the planet was wetter, and then adapted as it dried out.

"Life may therefore still exist, if only in a cryptobiotic state, subject to resuscitation whenever water becomes available," they explain.

They add that the sporadic appearance of methane points to methanogens - microorganisms that produce methane as a metabolic byproduct in harsh conditions - as possible Martian life-forms.

It's a long shot, and they know it, but what Levin and Straat hope will come from their 'renewed case for life' is a greater urgency from NASA and other space agencies to keep looking for signs of biological activity on Mars, and stricter policies when it comes to contamination risks.

"It is noted, however, that Mars may already have been infected by the many spacecraft that have landed there; although Viking was heat-treated to reduce microbial counts, no other spacecraft have been similarly treated," they caution.

The paper has been published in Astrobiology.