Scientists have analysed a strange depression on the surface Mars, and say it could be the perfect place to search for signs of life, because it could contain three key ingredients for life: water, heat, and nutrients.

The funnel-shaped structure looks like the ancient 'ice cauldrons' we have on Earth, that formed when volcanos erupted under the ice sheets of Iceland and Greenland. If the same process occurred on Mars, it could have left behind a warm, nutrient-rich environment.

"We were drawn to this site because it looked like it could host some of the key ingredients for habitability - water, heat and nutrients," said lead researcher Joseph Levy, from the University of Texas.

The funnel is located inside a crater on the edge of the Hellas Planitia region in the southern hemisphere of Mars.

The Hellas Planitia basin is actually just one big crater itself - the largest visible impact crater ever found in the Solar System, in fact - but it's pocked with many smaller craters, which suggests that it's a very old formation on the Red Planet.

The funnel was first detected by Levy back in 2009, because of strange crack-like features photographed by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

He then found a similar structure in the Galaxias Fossae region of Mars, located in another giant basin called the Utopia Planitia.

"These landforms caught our eye because they're weird looking," says Levy. "They're concentrically fractured so they look like a bulls-eye. That can be a very diagnostic pattern you see in Earth materials."

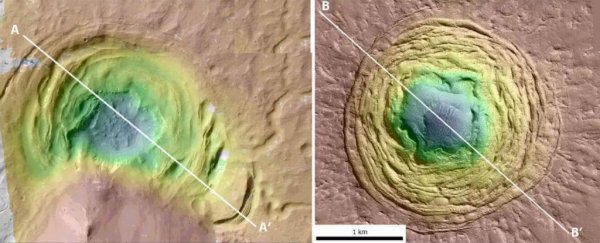

It wasn't until this year that Levy had the data to actually analyse the funnels properly, and thanks to new stereoscopic photographs - which allow researchers to extract three-dimensional information from two-dimensional image - his team could map out what they would look like below the surface.

Turns out, they're both shaped like funnels:

Joseph Levy et. al.

Joseph Levy et. al.

"That surprised us, and led to a lot of thinking about whether it meant there was melting concentrated in the centre that removed ice and allowed stuff to pour in from the sides," says Levy.

"Or if you had an impact crater, did you start with a much smaller crater in the past, and by sublimating away ice, you've expanded the apparent size of the crater."

Next, the researchers run a number of formation scenarios for the two funnels, and say the most likely result is that they formed in different ways to arrive at the same funnel shape.

They estimate that roughly 2.4 km3 and 0.2 km3 of material was removed to form the Hellas Planitia and Galaxias depressions, respectively - and this appears to have been predominantly water ice.

While the Galaxias funnel appears to have formed due to an impact on the surface of Mars, the Hellas Planitia one shows signs of volcanic activity.

The team found hints that rising temperatures from an ancient eruption could have melted or pushed away large slabs of ice to form the funnel - much like what occurs on Earth when ice sheets and volcanoes mix:

An ice cauldron in Iceland's Vatnajökull ice cap. Credit: Joseph Levy et. al.

An ice cauldron in Iceland's Vatnajökull ice cap. Credit: Joseph Levy et. al.

The team estimates that a whopping 105 m3 of magma would have been required to melt or shift so much ice, but it could have left behind so habitable conditions in the process, with ice melted to provide water, and the magma leaving behind nutrients and warmth.

"The possibility of liquid water formation during or subsequent to volcanism or an impact could generate locally enhanced habitable conditions, making these features tantalising geological and astrobiological exploration targets," they conclude in their report.

The hope now is that when NASA sends a rover to the Red Planet in 2020 to search for signs of life, this could be one of the places it investigates.

"These features do really resemble ice cauldrons known from Earth, and just from that perspective they should be of great interest," volcanologist Gro Pedersen from the University of Iceland, who was not involved in the study, said in a press release.

"Both because their existence may provide information on the properties of subsurface material - the potential existence of ice - and because of the potential for revealing ice-volcano interactions."

The study has been published in Icarus.