Scientists have found the earliest known use of a modern-day metalworking process in a 6,000-year-old amulet from Pakistan, showing that the ancient craftspeople who made it were way ahead of their time.

The process is called lost-wax casting, and variations of it are still used by NASA and many other manufacturers today. It involves making a wax cast replica of your chosen object, putting it inside a clay mould, and then replacing the wax with molten metal.

To get the six-spoked amulet to give up its origin story, a team led by the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) fired a high-powered beam of light on the artefact. This technique, called photoluminescence spectroscopy, uses light absorption and reflections to determine what metals are contained in an object.

The scientists noticed tiny rods of copper oxide inside the metal, suggesting that oxygen was accidentally let into the amulet as its makers tried to shape it from a single piece of copper. That, together with its non-symmetrical shape, points to lost-wax casting.

"We discovered a hidden structure that is a signature of the original object, how it was made," lead researcher Mathieu Thoury from CNRS's ancient materials centre told Sarah Kaplan at The Washington Post. "You have a signature of what was happening 6,000 years ago."

For photoluminescence spectroscopy to work, the light beams need to be powerful enough to excite the electrons inside materials, so that they emit their own spectrum of light in response.

Scientists can then analyse these, in this case giving them access to parts of the amulet that they otherwise couldn't see.

The technique revealed the metal ore used in the amulet (extremely pure copper), the level of oxygen it absorbed, and the melting and solidification temperatures (around 1,072 degrees Celsius, or 1,962 degrees Fahrenheit).

The photoluminescence technique (top) revealed copper oxide traces. Credit: T. Séverin-Fabiani/M. Thoury/L. Bertrand/B. Mille/IPANEMA/CNRS/MCC/UVSQ/Synchrotron SOLEIL/C2RMF

The photoluminescence technique (top) revealed copper oxide traces. Credit: T. Séverin-Fabiani/M. Thoury/L. Bertrand/B. Mille/IPANEMA/CNRS/MCC/UVSQ/Synchrotron SOLEIL/C2RMF

The introduction of lost-wax casting at this point in human history marked a major shift in the way metal objects were made. Before that, metalworkers used permanent mould casting, where the same metal moulds are used again and again.

Lost-wax casting allows for more complicated designs: knives, water jugs, tools, jewellery, even metal statues.

As The Washington Post reports, that giant Buddha statue at Tōdai-ji, ultra-expensive Fabergé eggs, and various NASA equipment all exist thanks to low-wax casting – or its successor, investment casting (basically a more complex version of the same idea).

This ancient amulet might not be quite as fancy or sophisticated, but it's nonetheless a powerful demonstration of scientific knowledge from several millennia ago.

"It is not the most beautiful object, but still it holds so much history," Thoury said. "It shows how the metalworkers at the time were so innovative and wanted to optimise and improve the technique."

The findings have been published in Nature Communications.

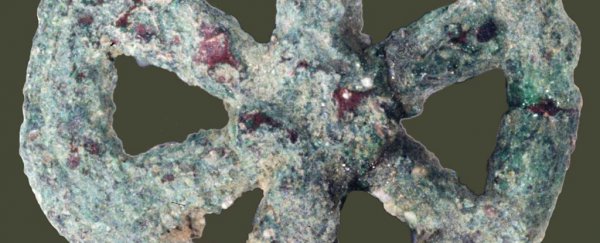

And finally, here's a full look at the historic amulent:

Credit: D. Bagault/C2RMF

Credit: D. Bagault/C2RMF