Brain connections in people with autism spectrum disorder ( ASD) show more symmetry across the right and left hemispheres, suggesting that tasks are being divvied up in the brain in a very different manner from those without autism.

The find, which is based on new brain scans of young people with autism, could explain why one of the hallmarks of the condition is an innate skill for identifying specific details in something, but a failure to put them into a wider context.

As researchers from the San Diego State University explain, the left and right hemispheres of the brain process information in very different ways, and how the brain as a whole mitigates this could help us better understand how people with autism spectrum disorder see the world.

While that old myth that the right hemisphere of the brain is more 'creative' and the left is more 'analytical' has been well and truly debunked - and despite what Oprah says, there's zero evidence that a person can be more 'right-brained' or 'left-brained' - we do know that certain functions are performed by certain hemispheres.

Studies have shown that the left hemisphere plays a much larger role in language processing and speaking than the right hemisphere, whereas the right hemisphere tends to focus on auditory and visual stimuli.

Researchers also suspect that the left hemisphere is more involved in analysing the specific details of a situation, while the right hemisphere is tasked with integrating these details and various other stimuli into a more cohesive whole.

The way these two hemispheres work together to combine their various functions explains how we perceive and respond to the world, and a new experiment has revealed that this occurs very differently in young people with and without autism spectrum disorder.

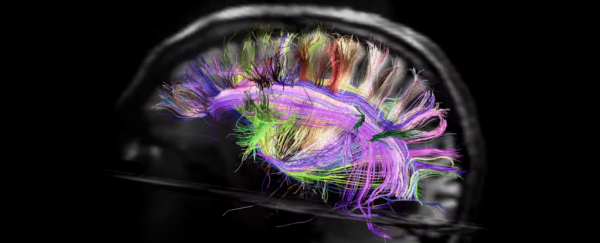

The San Diego State University team used a magnetic resonance imaging ( MRI) technique known as diffusion tensor imaging to visualise the brains of 41 children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and 44 without (referred to as "typically developing", or TD, participants).

They were particularly interested in analysing how dense the connections were within different regions of white matter across the two hemispheres.

They found that the "typically developing" participants had much more densely packed connections in the right hemisphere than in the left.

"This fits with the idea that the right hemisphere has a more integrative function, bringing together many kinds of information," the researchers explain.

But the scans revealed that the brain connections in participants with autism spectrum disorder were more symmetrically organised across both hemispheres.

"The idea behind asymmetry in the brain is that there is a division of labour between the two hemispheres," says one of the team, Ralph-Axel Müller. "It appears this division of labour is reduced in people with autism spectrum disorder."

To be clear, the experiment only looked at a very small sample size, so until the results are replicated in a much larger group, we can't read too much into them.

But they do correspond with results of a separate experiment from earlier this year, which found that mice with autism also had unusually symmetrical brains.

At this stage, the San Diego State team isn't clear on how this symmetry plays into the cognitive differences between young people with and without autism spectrum disorder, and they can't say for sure if the symmetry leads to autism, or autism leads to the symmetry.

But they do suspect that the lack of specialisation they've observed in the brains of kids with autism could contribute to the "weak central coherence" that characterises the condition - what Müller sums up as "not seeing the forest for the trees".

The research has been published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.