NASA's Cassini spacecraft has captured some of the closest-ever views of Saturn's rings, with new images revealing unprecedented levels of detail in the massive discs of icy particles orbiting the planet.

The new perspectives come courtesy of Cassini's "ring-grazing" mission phase, where the probe is making a series of orbital dives past the outer edge of Saturn's main ring system. These loops will be some of Cassini's last, with the almost 20-year-old spacecraft soon due to sacrifice itself, plunging into the gas giant this September.

"How fitting it is that we should go out with the best views of Saturn's rings we've ever collected," says Cassini Imaging Team Lead Carolyn Porco from the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

Cassini's ring-grazing dives began in November last year, and the space probe is about halfway through its final 20 orbits.

While NASA scientists have seen some of the features pictured here before, we've never had a chance to observe the main rings with such high-definition images.

The new shots resolve details as small as 550 metres (0.3 miles) – about the same scale as some of Earth's tallest buildings.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

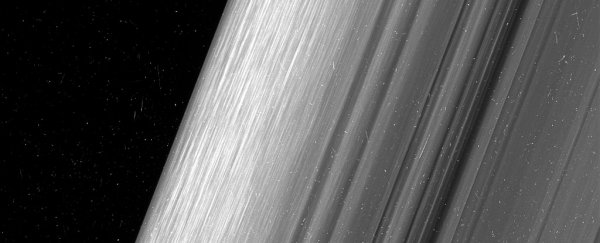

In the image directly above, you can see Saturn's A ring – the outermost of the large, bright structures, which lies about 134,500 km (83,574 miles) from Saturn.

The rippled appearance is what's known as a density wave, made up of icy particles that clump together into shapes that the scientists informally call "straw".

The grazing orbits bring Cassini so close to another of Saturn's rings – the F ring – that small particles even strike the probe as it passes.

"These are very small and tenuous, only a few microns in size, like dust particles you'd see in the sunlight," Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker said during a Facebook Live event this week.

"We can actually 'hear' them hitting the spacecraft in our data, but these particles are so small, they won't hurt Cassini."

Saturn's outer B ring. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Saturn's outer B ring. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The spacecraft actually got closer to the rings than this when it first arrived at Saturn 13 years ago, but the quality of the images it snapped back then wasn't as good, for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, the probe was moving extremely fast on its initial pass by the rings in 2004, so the NASA team had to opt for very quick exposures to help minimise blurring. The rings were also only back-lit by the Sun, making for somewhat dark, grainy images.

By contrast, the glorious new shots were taken with longer exposures, allowing for brighter, more detailed pictures.

And the opportunity to observe the rings both back-lit and directly front-lit by the Sun makes for some exquisite views of the surreal, icy debris that's gravitationally bound to Saturn.

"As the person who planned those initial orbit-insertion ring images – which remained our most detailed views of the rings for the past 13 years – I am taken aback by how vastly improved are the details in this new collection," says Porco.

But as exquisite as the new snaps are – not to mention this stunning up-close glimpse of one of Saturn's moonlets hiding among the rings, which NASA shared last week – the wonderment is only going to increase as Cassini approaches its final mission phase.

Saturn's outer B ring. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Saturn's outer B ring. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Dubbed the Grand Finale, the space probe's 'death spiral' will begin on April 26, with the first of 22 orbits much closer to Saturn, as Cassini dives through the gap in between the planet and its rings.

These dives will give the spacecraft a final look at the Saturn's innermost rings and the planet's gas clouds, before one final orbit will end with Cassini plunging into the Saturn's upper atmosphere on September 15, where it will burn up like a meteor.

Why the fiery death instead of a noble, prolonged retirement exploring more of Saturn and its moons?

The rationale is that two of Saturn's moons – Enceladus and Titan – are both thought to feature habitats that could potentially sustain life.

Saturn's A ring, with blemishes due to cosmic rays and charged particle radiation near the planet. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Saturn's A ring, with blemishes due to cosmic rays and charged particle radiation near the planet. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

And just in case they do, NASA doesn't want to jeopardise any alien organisms living on them by bringing them into contact with microbes from Earth that may yet survive on the spacecraft – however slim that possibility might seem.

But while it will be sad to lose Cassini – especially in light of the venerable probe's long years of service and scientific discovery – it's going into the night for the most honourable of reasons.

And it's sure to provide some more fantastic observations when it makes the final plunge.