Researchers have found a brand new type of insulin-producing cell hiding in plain sight within the pancreas, and they offer new hope for better understanding - and one day even treating - type 1 diabetes.

Type 1 diabetes occurs when a person's own immune system kills off most of their insulin-producing beta cells. And seeing as insulin is the hormone that regulates our blood sugar, type 1 diabetics are left reliant on injecting themselves with insulin regularly.

While the condition can usually be managed effectively, in order to properly treat it, researchers would need to find a way to regenerate a patient's beta cells and prevent them from being attacked in future - something we're getting better at, but ultimately has eluded scientists so far.

The discovery of these previously unnoticed cells in the pancreas - which the team are calling 'virgin beta cells' - could offer a new route for regrowing healthy, mature beta cells - and also provides insight into the basic mechanisms behind the disease.

"We've seen phenomenal advances in the management of diabetes, but we cannot cure it," said lead researcher Mark Huising from the University of California, Davis.

"If you want to cure the disease, you have to understand how it works in the normal situation."

To get a better insight into exactly what happens in type 1 diabetes, the researchers studied both mice and human tissue.

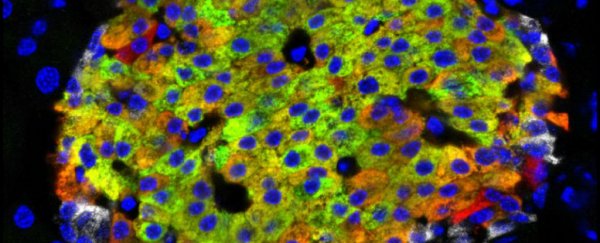

Huising and his team were looking at regions inside the pancreas known as the islets of Langerhans, which in healthy humans and mice are the regions that contain the beta cells that detect blood sugar levels around the body and produce insulin in response.

Researchers also know that the islets contain cells called alpha cells, which produce glucagon, a hormone that raises blood sugar. These alpha cells, combined with the blood sugar-lowering beta cells, are how the body regulates blood sugar levels.

But in patients with type 1 diabetes, two things go wrong: the beta cells are killed off by the body's own immune system, and then they fail to regenerate.

In order to treat the disease, we need to find a way to overcome both of those problems.

For decades, scientists have been trying to do this, and they had long assumed that there was one main way for beta cells to be produced - through other adult beta cells dividing.

But after using new microscope techniques to study islet tissue in the lab, Huising and his team found a new type of cell scattered around the edges of the islets that no one had noticed before - and they looked a lot like immature beta cells, suggesting that maybe there was actually another way beta cells were being made.

Further study revealed that these new virgin beta cells could make insulin, but they didn't have the receptors to detect glucose, so couldn't function as mature beta cells.

But that wasn't all the researchers found. They also observed some mature beta cells in the islets transitioning into alpha cells - representing a completely unexpected alpha cell generation pathway.

"There's much more plasticity in the system than was thought," said Huising.

It's still very early days, and these new cells now need to be confirmed in live humans and animals - not just tissue in the lab. But the fact that we now have evidence that they exist opens up a whole avenue of research on type 1 diabetes and potential treatments.

According to Huising, there are three main reasons to get excited about the result: firstly, it represents a new beta cell population in both humans and mice that we had no idea about before, and secondly, it also provides a potential new source of beta cells that could be used to treat diabetics.

"Finally, understanding how these cells mature into functioning beta cells could help in developing stem cell therapies for diabetes," a press release explains.

The research could also have benefits for type 2 diabetes, which occurs when beta cells become inactive and stop releasing or secreting insulin.

The results have been published in Cell Metabolism.