The first continent-wide survey of its type has spotted a worrying trend on the glaciers of Antarctica: meltwater streams that are far more widespread than previously thought, suggesting the frozen continent is even more vulnerable to future temperature rises than predicted.

While a lot of the drainage channels that have been spotted aren't new, the new footage recording during the survey has scientists concerned about how far they stretch, and how soon they might send Antarctica's ice shelves crashing into the ocean.

The research, by a team from The Earth Institute at Columbia University, carries on the work of measuring the Antarctica melt streams that began in the early 20th century.

Now though, we have the technology to build up a much more comprehensive picture of where these streams are flowing.

Unfortunately, the picture isn't a particularly pretty one.

"This is not in the future – this is widespread now, and has been for decades," says one of the researchers, glaciologist Jonathan Kingslake.

"I think most polar scientists have considered water moving across the surface of Antarctica to be extremely rare. But we found a lot of it, over very large areas."

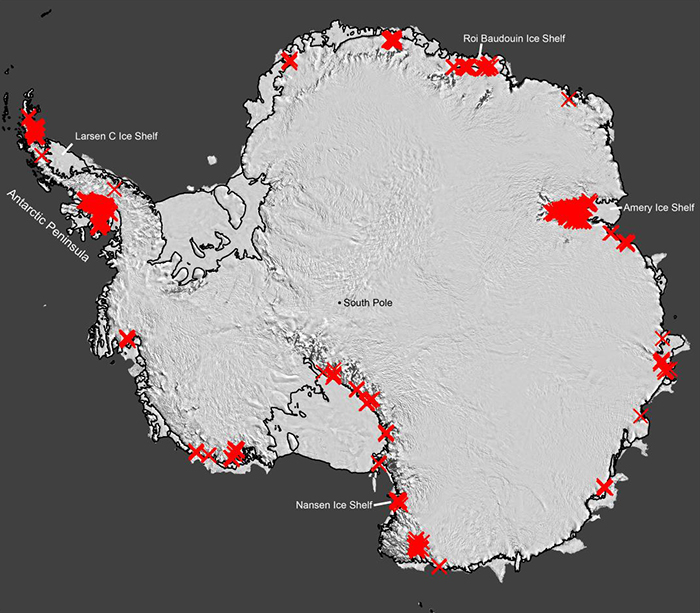

In total, nearly 700 seasonal ponds and channels streams were found, with some streams as long as 121 kilometres (75 miles).

Meanwhile meltwater channels have been spotted as close as 604 kilometres (375 miles) to the South Pole, some 1,300 metres (4,300 feet) above sea level – places where it was thought it was impossible to have running water.

You can see a 122-metre-wide (400-foot-wide) waterfall draining off the Nansen Ice Shelf into the ocean in the video below:

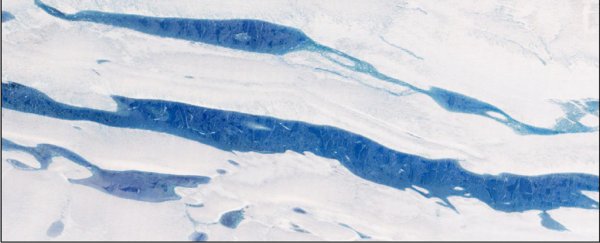

Many of the newly mapped channels start in mountains that poke between glaciers, or in areas where winds have whipped the snow covering off bluish ice.

As these areas are darker, less sunlight is reflected, and melting increases, with streams washing away even more snow.

This meltwater usually refreezes in winter, and it's thought this process isn't contributing much to Antarctica's ice loss just yet. The concern is that if the continent continues to get warmer, the whole cycle speeds up.

"This study tells us there's already a lot more melting going on than we thought," adds one of the team, polar scientist Robin Bell.

"When you turn up the temperature, it's only going to increase."

Each red 'X' represents a separate drainage point. Credit: Columbia University

Each red 'X' represents a separate drainage point. Credit: Columbia University

Another concern is the ice shelves that ring Antarctica and protect its glaciers from floating out to the sea and warmer ocean currents: running liquid could help to fracture these shelves, through heat and pressure, leaving the continent more exposed.

Nothing is clear-cut yet though, and researchers spotted another meltwater stream channel on the Nansen ice shelf that they think might be helping to keep it together, by efficiently removing water from the shelf out to the ocean.

Scientists are also studying Greenland for clues as to how these streams might develop and affect sea level rises – between 2011 and 2014, about 70 percent of the 269 billion tons of ice and snow lost by Greenland to the oceans was due to meltwater.

The positive news is that we now have information data than ever before about what's happening with meltwater in Antarctica, and that should help us understand more about how the ice could shift in the future.

Because meltwater streams were thought to be relatively rare in Antarctica before this, they haven't been extensively studied in the past, according to glaciologist Douglas MacAyeal from the University of Chicago, who wasn't involved in the study. Now, that's changing.

"We're working hard to figure out if this stuff is relevant to sea-level predictions," he says.