Scientists have found evidence of what could be the oldest fungal life on the planet, discovering traces of microfossils buried in ancient volcanic rock dating from some 2.4 billion years back.

The discovery was identified in hardened lava formations found 800 metres (2,625 feet) below South Africa's Northern Cape, and if confirmed, it wouldn't just rank as the world's oldest known fungi, but could make scientists have to rethink a few things on how early life on Earth came about.

Geologist Birger Rasmussen from Curtin University in Australia made the find by accident when examining basalt samples extracted from the Ongeluk Formation – a region made up of volcanic rock that once flowed as lava under the seafloor.

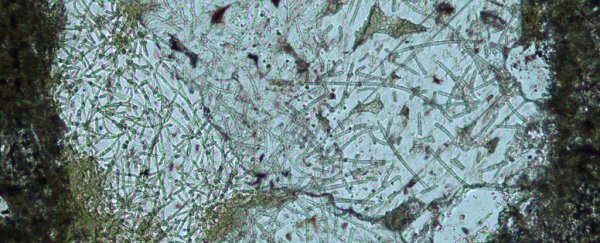

"I was looking for minerals to date the age of the rock when my attention was drawn to a series of vesicles, and when I increased the magnification of the microscope I was startled to find what appeared to be exquisitely preserved fossilised microbes," says Rasmussen.

"It quickly became apparent that cavities within the volcanic rocks were once crawling with life."

When Rasmussen shared photographs of the discovery with fellow researchers, including paleobiologist Stefan Bengtson from the Swedish Museum of Natural History, the significance of the microfossils became clear.

"I showed them and they went quiet," Rasmussen told Ben O'Shea at The West Australian.

Up until now, previous geological evidence for fungi only extended as far back as 385 million years ago, but the fossilised traces of microscopic creatures found in the volcanic rock were a whole 2 billion years older.

That said, the researchers aren't claiming that what they've found is definitely evidence of ancient fungi – although signs are positive, as the appearance of tangled filaments is highly similar to other fungal fossil discoveries.

"This is why we call the fossils 'fungus-like' rather than 'fungal'. We have been careful to point out that the filaments we see are very simple," Bengtson told Jerry Redfern at Seeker.

"[But the fossils] are practically indistinguishable in habitus and habitat from the proven fungi in the much younger fossil record. We were quite excited that the fossils were so fungus-like."

If subsequent research can verify that the discovery was left by a type of ancient fungus, it would also be the earliest fossil evidence of eukaryotes – the biological kingdom of organisms that also contains fungi, in addition to animals and plants.

Curtin University

Curtin University

But the biggest implications of the research could be that it suggests fungi may have evolved under the sea, rather than on land as previously thought.

The dating of the ancient basalt to 2.4 billion years ago means the organisms existed before what's called the Great Oxygenation Event – which possibly occurred 2.3 billion years ago, dispersing dioxygen (O2) into the atmosphere.

By predating this event, it means the life-forms evolved to survive deep under the sea, without access to either light or oxygen.

The team suggests the fungus-like organism may have existed in symbiosis with other microbes, somehow using chemically stored energy to stay alive.

"This would have tremendous implications for the lifestyle of the early ancestors of eukaryotes and fungi," Rasmussen told AFP.

In addition, the research shows that scientists stand to learn a lot from studying the deep biosphere – the hidden terrain of the ocean floor and the ecosystems underneath it.

"The deep biosphere (where the fossils were found) represents a significant portion of the Earth, but we know very little about its biology and even less about its evolutionary history," Bengtson told Helen Briggs at BBC News.

In light of these findings, now could be the time to address that lack of knowledge, by digging a little deeper.

"The [research] raises the question of whether we have been looking in the wrong place for the earliest eukaryotes and fossil fungi in particular," writes geologist Nicola McLoughlin from Rhodes University in South Africa, who wasn't involved with the study, in a commentary on the paper.

"Perhaps we have."

The findings are reported in Nature Ecology & Evolution.