Scientists studying the pattern of circadian rhythms have found that one central body clock could be controlling several others at the same time.

By examining fruit flies - which, like humans, have several circadian clocks affecting the rhythm their daily biological processes - researchers have found evidence of a single 'master' clock that leads all other internal clocks related to sleeping and eating patterns, and various organ functions.

The team says this finally gives experimental proof for the so-called coupled-oscillator model moderating the daily rhythms of our physiology and behaviour.

"This is the first comprehensive experimental description of a pathway that links circadian clocks, and it shows that the coupled-oscillator model is actually true in certain cases," says one of the researchers, Christian Wegener from the University of Würzburg in Germany.

The team focussed on a neuronal pathway (the hyperthetical master clock) that linked the circadian clock in the brain of the fruit fly with a peripheral clock in its prothoracic gland, which is responsible for producing steroid hormones.

This gland was chosen because it gives the signal for the fruit fly to hatch - a strictly timed process that usually happens in the early morning.

From previous studies of fruit flies, we know that both the brain clock and the gland clock are involved in timing the hatching. The question is, how do they sync up?

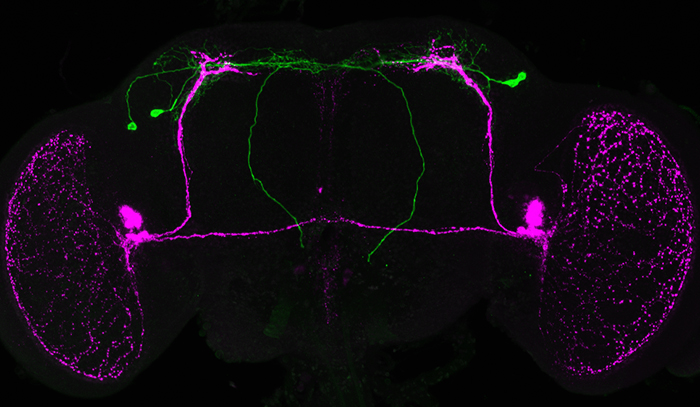

PTTH neurons (green) connected to the circadian clock (magenta) in a fruit fly. Image: University of Würzburg

PTTH neurons (green) connected to the circadian clock (magenta) in a fruit fly. Image: University of Würzburg

The team was able to identify certain types of neurons, called PTTH neurons, relaying time information from the central clock in the brain to the peripheral clock in the prothoracic gland.

Then in follow-up experiments, the circadian clocks of fruit flies were slowed down, and the hatching rhythm stretched to a 27-hour cycle from its usual 24-hour one.

The same effect was noticed when only the central brain clock was slowed, again resulting in a 27-hour hatching cycle.

Meanwhile, when the central brain clock was left to work normally, and the peripheral gland clock was slowed down, the hatching rhythm stayed at 24 hours.

This suggests that it's the master clock doing the time regulation - at least in this particular case. And because the neuronal pathway being studied is similar to a system found in the circadian rhythm of mammals, it could apply to humans too.

More research is needed before we can be sure about that, but it's another sign that our brain's master clock keeps the others ticking over.

In humans, the master clock is thought to be located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus - part of the brain's hypothalamus region, made up of around 20,000 neurons.

This region uses cues such as daylight to figure out when we should be sleepy and when we should be wakeful.

Exactly how all these clocks and biological messengers work together is something scientists are still investigating.

And the more we know, the better we can keep ourselves healthy.

Jet lag is just one of many examples where a slip in this finely balanced system causes us to feel pretty rotten, and staying up late watching Netflix doesn't seem to be helping either.

Thanks to the fruit fly, now we know a little more.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.