It may sound like something out of a sci-fi novel, but researchers have found a way to power micromotors with the help of swimming bacteria. For the first time, the team were able to make the tiny propeller-like structures spin in the same direction by adjusting the light conditions.

The new micromotors can be produced in large amounts at a low cost, and could be used to deliver targeted drugs to treat disease.

"We can produce large arrays of independently controlled rotors that use light as the ultimate energy source," says Roberto Di Leonardo, lead author from the Sapienza University of Rome.

"Our design combines a high rotational speed with an enormous reduction in fluctuation when compared to previous attempts based on wild-type bacteria and flat structures."

They may be tiny at less than one millimetre, but microbots are set to to make a huge impact in a variety of applications, from improving drug delivery and disease diagnosis to moving huge objects such as cars, just like a team of ants.

Over the last decade, researchers have explored how bacteria can be used to power these minuscule machines. One study demonstrated that light signals can be used to control the movements of bacteria, which in turn propel the motions of microrobots.

While the researchers were able to get the microrobots moving, they weren't able to get them propelling at the same speed due to the chaotic movements of the bacteria. The tricky part is bacteria-filled liquids can only be a viable source of fuel for microrobots if the bacteria all move in the same direction.

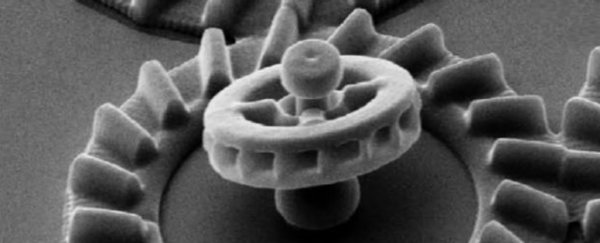

To tackle this problem, Di Leonardo and his team constructed a micromotor which could house a smooth-swimming, light-sensitive strain of E. coli. On the outer edges of the tiny motor's spinning unit were 15 chambers with angled ramps.

When the bacteria swam towards the micromotor, the angled ramps pushed them head first into the chambers. The motion of their flagella caused the micromotors to spin, powering the micromotor in a similar way to how flowing water rotates a watermill.

Next, the team exposed the array of micromotors and swimming bacteria to a light source. They were able to adjust the light levels using a feedback algorithm that illuminated the array at 10 second intervals.

By adjusting the light, the researchers were able to get each of the micromotors spinning in the same direction at almost the same speed.

"These devices could serve one day as cheap and disposable actuators in microrobots for collecting and sorting individual cells inside miniaturised biomedical laboratories," says Di Leonardo.

The research was published in Nature Communications.